Stop asking "when?". The US has already defaulted!

Large sovereigns can always choose not to hard default, but a soft default from inflation causes more capital loss than you think

The dominance of fiscal over monetary policy has finally become mainstream.

My prior work in quantifying the direct effect on growth of fiscal stimulus, which, unlike monetary policy, does not have “long and variable lags” associated with it, has predicted the strapping pace of US GDP growth which at this point doesn’t seem like it’s going to stop.

The next natural question is: how long can this go for? Won’t the US government default if it keeps on going down this path?

The short answer is the US government will only default if it explicitly chooses to. It will, however, continually cause losses to bondholders like it did in the 1970s and through the post-pandemic inflationary episode. Negative real returns are economically no different to a default and restructure in terms of losses to capital.

Warning: This newsletter is long. Skip ahead to the section entitled “the truth and beauty of inflation” to see the hard numbers on bondholder haircuts. It’s bigger than you expect.

Misinformation about hard defaults is rife. For a country like the US, I can categorically say that:

A default won’t happen at a random failed auction for US government debt.

A default isn’t any more likely because measured bid-ask spreads in government debt are getting wider or any random liquidity measure is degrading.

A default won’t happen because foreigners all of a sudden have decided not to buy government debt (even if we assume they can collude without fault on this).

Ignore anyone peddling these theories because, frankly, they have exactly zero merit.

The fact is that any country that has sovereignty over their own currency always has a choice over whether it defaults or not. If a country has the ability to create its own currency, it can always manufacture a buyer of its own government’s debt. This is an undeniable fact.

This requires us to change how we think about default for developed nations with sovereignty. A “default” need not be just an inability to deliver on promises of coupons or principal. They can be any action that results in a negative real return for bondholders, since the link between fiscal policy and inflation is strong.

Stoking inflation by spending with no regard to debt growth reduces the value of nominally defined government debt. A common misconception here is that the creation of the money is what causes inflation. This is wrong. It is the spending of irresponsibly generated money in a resource constrained system that creates inflation.

Print as much as you want and leave it in a vault and it will have no effect on inflation.

Buying debt is a transaction where you exchange your current dollars for a payment of interest which should more than offset the erosion of the future spending power of those current dollars because of inflation. If that value is eroded by more than you expect then you have taken a loss that is no different to a hard default and a haircut on your capital. These two things are one and the same.

A negative real return on a sovereign bond can be classified as a “soft” default. Whether it is a soft or hard default is irrelevant to the bond holder, as it is still a loss of capital.

The pandemic was a dangerous mix of supply-side contraction and demand expansion, something which (thankfully) made it unique. The outlook isn’t as clear now. The same countries we worry about inflation-driven defaults about also run large deficits with an exporting powerhouse that is doing everything it can to reduce prices of its exported goods - a strong deflationary impulse.

These effects make it very hard to anticipate when stresses that large fiscal deficits cause become too big to ignore.

All that is sure is that the floor for 10-year+ government bond yields is much higher than it has been in 50 years. This doesn’t mean that the immediate impulse is for higher bond yields - just that nearly every other risk asset presents a better outlook than bonds do.

Domestically, the power is all yours

As a general rule, a sovereign that has a central bank that can (and is willing to, if “independent”) fund the local currency denominated banking system to an unlimited scale cannot default on its sovereign debt.

To understand why, it is important to know how government bond auctions are carried out.

While exact methodologies differ between countries, most advanced countries issue government bonds through the banking system, who then conduct the process of allocating that issuance to the final investor. The key part here is that the banking system (operating as primary dealers) implicitly funds the entire issuance. This occurs through repo funding any gaps and through backstop support through facilities such as a discount window at their local central bank. The result is that the banking system underwrites the entire issuance of a new government bond issue (with the important help of unlimited support from the central bank).

The final investor sets the price for bond issue, however. In normal circumstances, the bank will only hold onto the amount of debt that it wants for its trading desk or perhaps for regulatory purposes. It lets the rest of the market set the price, which is made up of mutual funds, insurers, other financial institutions and households.

Sometimes demand wanes for some reason. This generally happens when the near-term outlook for bond yields may not be favourable, so less demand comes through than normally does. Sometimes new issuance may be mispriced on the yield curve, although this is rarer given the consultation with traders that occurs before an issue goes live.

The famous “bid-to-cover” ratio that are published at every US government bond auction has very little correlation with subsequent bond price performance over any time period.

For those that are familiar with equity markets may be confused as to how variable demand doesn’t just kill issuance. It is true that IPOs can live or die based on whether they are oversubscribed or not.

Government bond markets are different. The difference with sovereign debt is that it is not only the bank that underwrites the deal, but the central bank as well. Most advanced economy central banks have a litany of programmes that allow them to accept government bonds as collateral in return for funding.

While these programmes may have different names and mechanisms, they all are a slightly different form of creating central bank warehousing space for risk the market doesn’t want to take for whatever reason.

This is difficult to say, but technically Modern Monetary Theory cultists are right; just spending more doesn’t necessarily cause a problem and is without limit. Where they are wrong is that just making new money in the form of debt doesn’t change the true limits of labour, manufacturing capacity and raw materials availability.

The foreign buyer of government debt

Second to the debunked possibility of a failed government bond auction is the constant threat, regularly pushed by the financial media, of foreign governments that can just stop buying your debt at any point in time. This fills many with fear, and on the surface makes my assertion that developed economies with control over their own currency can choose if they default, false.

In some ways, it does make it false. A country that has control over its own currency but also has a very large current account deficit is more at risk of an uncontrolled default than a than one that has a balanced current account. The bigger the current account deficit, the more your country relies on capital inflows in the form of equity or debt to pay for your over consumption relative to the rest of the world.

This risk increases the smaller a country is. A country small enough can experience a buyer’s strike on their debt, and while this doesn’t affect the ability of the government to raise funds through debt issuance, it does affect the willingness of other countries to accept their currency as payment for imported goods and services.

“We’ll only sell to you if you pay us in a currency you can’t create out of thin air, please. And if you can’t, why am I selling it to you at all?” will be the very appropriate question asked by exporting countries.

This thought process is why small and open countries peg their currency to another (“hard”) currency instead. This avoids this question being asked at all, while introducing a whole host of other compromises.

Within this argument, size clearly matters. A small market for foreign goods like Argentina is easy to switch off. A larger market like New Zealand is harder as export competitors who are willing to take that currency risk (or find a way to structure around it) may step in and take your market share.

An Australia, Canada or UK will be more resilient to foreign buyers strikes for their debt because of their bigger size. If you want to sell your stuff to a country, you must accept their currency as payment (which is analogous to saying you accept their debt).

The US is the end of the road for these comparisons. It runs the largest trade deficit in the world is currency equivalent by far yet still finds reliable buyers for its debt offshore. Why?

If foreigners want to keep selling their wares to the US, they need to accept payment in USD denominated assets. That can be equity, debt or anything in between. They don’t care what it is, because the US has a market for most goods and services that is unmatched by anyone else. A small business can become huge with only a small footing in the US.

This is without mentioning the size of the offshore market for US dollars. The Eurodollar market is as large as it is because so many foreign entities (both sovereigns and corporates) love borrowing in US dollars because of the stability it provides as a medium of exchange. Finding an investor for your government/corporate is far easier when everyone agrees on a valuing currency as a starting point.

The reality is that it doesn’t matter what they buy in the seniority ladder. Each will cycle money though the US economy, allowing it to continue to spend and maintain its external imbalance. Similarly, the availability of funding through the external imbalance encourages over-consumption.

As is the ultimate point of this newsletter, when you are big and important enough, you get to choose your outcome, which includes avoiding a hard default. In this timeline, the US chooses to overconsume by accepting foreign capital, and foreign exporters choose to keep on funding overconsumption, and seemingly encouraging it.

Either side could choose to end the status quo, but they just…don’t. If China decided tomorrow to stop accepting the US dollar as payment and as a result stop exporting to the US, who would that hurt more? Similarly, if the US government decided to close its fiscal deficit in a day, it would take the whole world with it.

We’ve seen defaults in the past, haven’t we?

Up until now, all it sounds like I’m saying that a sovereign can’t default unless it can. And, whilst rare, we’ve seen a number of defaults, with some of those within history of trading markets for some.

Did Greece hard default in the Euro crisis? After a flip-flopping by the Greek government of the time and basically reneging on a referendum by the people, it accepted the “help” of the German government and the ECB to provide the same support a large country with the ability to backstop government issuance could.

Greece suffered from large (larger than anyone apart from Goldman Sachs knew) fiscal deficits and, like most peripheral European countries, a very large current account deficit which mostly persisted with their saviour country, Germany.

I personally count Greece as a sovereign default, as the subsequent terming out of existing Greek debt was effectively a haircut to holders. This sort of restructuring, common in corporate defaults as well, is just a more orderly form of default over the chaos that would occur if there was a sudden stop.

The ECB’s commitment to buying the debt of its member states likely saved Spain, Portugal, Ireland and Italy from the same fate. For these countries no other losses were taken as they were for Greek government debt. Just an important example of how having co-operation of your central bank (and the ability to print your own currency) is important to the inherent choice of whether you default or not.

The European crisis also shows that buying your own debt and employing monetary measures (or as I prefer calling it, financial engineering) to avoid default doesn’t necessarily cause inflation, when paired with austerity.

This lends more credence to the theory that financial engineering doesn’t matter, it is only fiscal prudence (or the lack of) that does.

Most other defaults in the 21st century are filed under sovereigns that didn’t have control of the currency their debt was denominated in. Argentina and every country the experienced trouble during the Asian Financial Crisis falls in this bucket.

We need to go much further back to analyse examples of sovereign defaults that were significant but looked different.

16th century Spanish fiscal spending on naval projection was paid for with a constant inflow of silver from the new world. The reliability of this inflow helped to maintain the spend required for Spain to be the equivalent of a world “superpower” in its day.

This inflow brought economic problems that are shared with the US today. Inflation caused by this monetary inflow both killed productivity within Spain itself, reducing a once powerful industrial machine back to an agrarian economy. France and Britain increased their output of capital goods at the same time, further placing Spain under pressure.

This all eventually led to defaults on debt owed to other European powers. The parallels present here with the modern-day US are concerning both from the perspective of large inflows causing inflation, and the offshoring of industrial capacity eventually destroying the ability to service the debt attached to these inflows.

The Ottoman empire experienced something similar in regard to defaults associated with offshoring of industrial capacity.

Both the Spanish and Ottoman experiences are something I will revisit in a future newsletter because the history here is important. Modern financial systems are more adept at putting off crises, but the lessons from history still hold true. Large persistent capital inflows will eventually cause issues.

The most damaging of these issues is inflation.

The truth and beauty of inflation

We’ve established for a sufficiently large country with control of its own currency; default is a choice that can be taken at any time it serves itself.

Within this small subset of examples, the experience of the US in the 1970s is one that is incorrectly attributed to only the external factor of the oil shock, and the monetary factor of Arthur Burns not raising rates early enough in the late 1960s.

The inflation of the 1970s was caused in large part by the spending plans of LBJ. The expansion of the welfare state was unprecedented and caught an economy that was still running on all cylinders unaware.

Was monetary policy mismanaged? We can work that out on whether bond holders took an effective haircut (a soft default) or not.

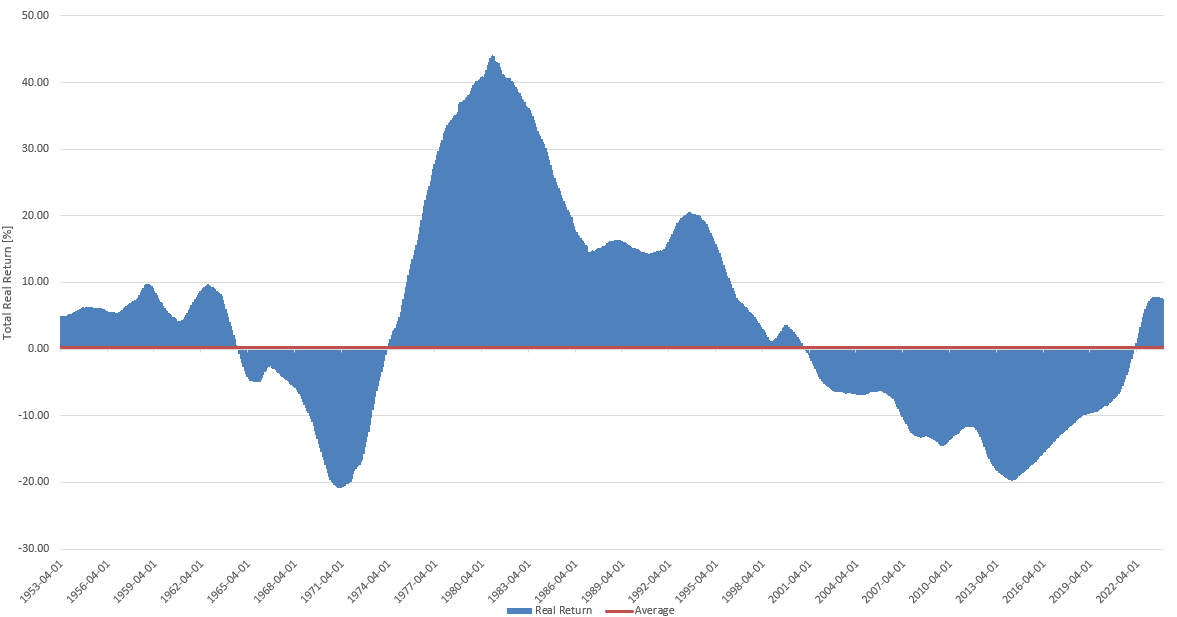

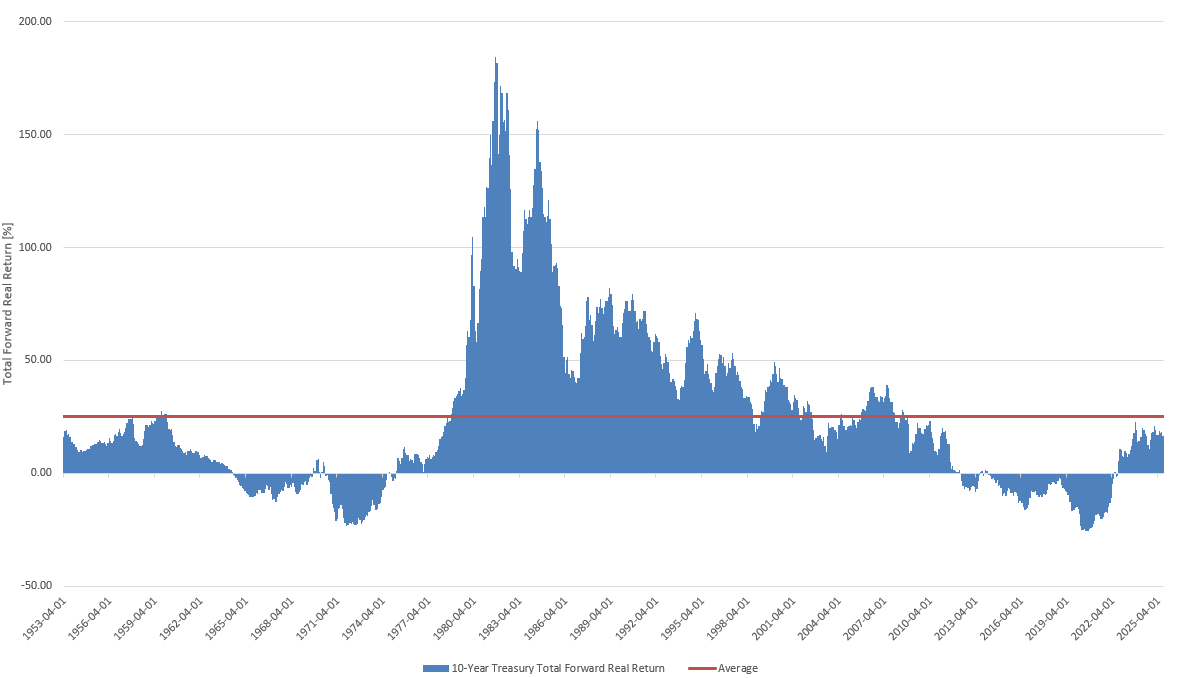

The chart above tracks the subsequent real return the buyer of a 10-year Treasury note would receive, expressed in total return over the entire 10-year period (rather than a per annum figure).

Looking closer at the chart above, if you bought a 10-year Treasury note at the end of November 1971, your total real return (i.e. not per annum) on that bond would’ve been -23.27%. This was the worst time to purchase a 10-year bond in this entire episode. The investor effectively experienced a haircut of a quarter of your capital (in real terms). This is the sort of loss a bondholder might receive in the restructuring of corporate debt in a mild bankruptcy.

For the decade of negative real returns (1964-1974), bondholders achieved an average real return of -9.27%. This includes a slight period of positive returns in late-’69 to mid-’70. This experience was distressing enough that it took 50 years for bonds to stop offering enormous real rates of return. Similarly, it shouldn’t be hard to understand why bonds found their way into every optimised portfolio given this performance!

The inflation episode of the 2010s and ‘20s also lasted a decade starting in April 2012 and ending in August 2022.

Important note (also covered here): Future inflation is estimated at 2.7%. These results don’t change by much if you assume inflation falls back to 2% by 2028.

The worst time in this episode to buy a 10-year bond was in July 2020, where the total real return was -25.61%, worse than in the 1970s!1 This seems surprising. Inflation didn’t get as high, rates weren’t hiked as much, but losses were bigger. The answer is that inflation rose faster and there was too much of a lag for rates being hiked. The gap was larger for longer than in the ‘70s for this reason.

The average real return over this period was -9.90%, again worse than during the oil shock. This average is worse than in the ‘70s as the large negative real returns in 2016 and 2017 (due to ZIRP) drag down the results in this century.

So not only was the Fed too slow to hike for 2021 inflation, but it ran such loose policy for so long that the average outcome was even worse.

So, while the recent inflation episode wasn’t as bad as in the 70s, the lower starting yields made losses far worse.

I struggle to understand why bond market participants worry about losing “independence” at the Fed. It’s not like an independent Fed treated them well anyway!

The average for the entire 75-year period is 25% total real return on a 10-year bond, or a 2.25% real return per annum. Most of this real return comes from the general decline in inflation over this horizon, giving a boost to real returns.

Considering all of those other asset classes is outside the scope of this newsletter. Equities, most real assets (and gold) kept up with inflation. This is to be expected, however. An soft default by the government should benefit those sectors that received the benefit of the excess government spending. A default it nothing but the crystallization of previous value transfer from one group of individuals to another, after all.

Cash (or bank account) holdings are worth considering as well. They are the lowest hurdle benchmark, but more importantly the outcome on cash balances which is more sensitive to the central bank’s response to the inflationary episode. Cash returns are nearly perfectly correlated to central bank interest rate (unlike the 10-year yield which is only about 70% correlated), so if the central bank adjusts rate correctly for the inflationary episode, a “default” can be averted.

Cumulative losses in the 1970s here were better than that for bonds, but only slightly. Returns under paced bonds as inflation fell, leading to an average real return of zero on cash over that period.

The real losses on cash in the 21st century that surprised me. From the point that Fed policy became focussed on deflationary risks, real returns on cash turned negative (as did the equity and bond correlation). This was the (misguided) point of ZIRP.

This chart directly illustrates why bonds became strongly negatively correlated with risk assets. Once this ended, so did that negative correlation. See below for more.

The large difference in average real 10-year returns between cash and bonds also highlight the benefit of a normal shaped curve. The difference (~25%) is roughly 2.5% per annum over the 10-year measurement period - the average yield curve steepness over that time.

The last cut to the Fed Funds rate has suggested that the Federal Reserve is comfortable with an inflation rate that is closer to 3% than 2%. This in itself will be a major determinant of forward inflation rates (by far the single most important factor for inflation expectations is inflation of the recent past).

Losses on bond positions can be thwarted by either a reduction in the US fiscal deficit or a China that is able to continue to deflate export prices at a greater rate than they have been able to in the past.

If neither of these conditions can be met, then bonds will struggle.

Does anyone benefit from this haircut? Again, if we liken it to a corporate restructuring, the main beneficiaries of that default are all of those who were paid prior to bankruptcy - either through selling an asset to the insolvent firm at an inflated price, or from getting paid to do work that otherwise wouldn’t have been done.

In the case of a default of a company that built an asset that wasn’t economically viable, the default allows future users of that asset to benefit from something that wouldn’t have otherwise been built if it wasn’t for the “donation” by the bondholders.

The beneficiaries in these examples are theoretical and tough to identify, but they do exist.

If it was government spending that caused the inflationary episode, then it was those who benefitted from that government spending (and managed to invest it in assets that did keep up with inflation). If it was due to decree (a change in law that constrained supply) then the benefits accrued to those industries where prices went up the most.

Identifying those groups in the US that benefitted is politically dangerous. With social security and other benefits making up the lion’s share of spending, it is the poor, the sick, and the elderly that may have benefitted from it the most.

Ironically, it is inflation that has made it unlikely that these groups have been able to subsequently invest this money into assets that have appreciated in a real sense. Therefore, it is corporate US that is the ultimate beneficiary of the spending this fiscal deficit has funded, and the buybacks they’ve enabled.

No wonder US equities perform as they do.

Bonds aren’t the only loser

The outcome for Treasury notes from the pandemic inflation worked out worse for bondholders than the 1970s inflationary episode largely due to the lower starting point for interest rates.

ZIRP policy left almost no premium in bond yields for the possibility of inflation unexpectedly exploding like it did, so ex-post returns were worse despite a much lower peak in inflation.

The inflationary episode of the 70s also birthed a 50-year bull market in bonds. Much of this is from the very high starting point for yields after an economically rough decade and the normalisation of inflation coupled with falling “economic volatility” (the uncertainty of what GDP growth or inflation will be).

Another important trend was academic consensus about the power of monetary policy in defeating inflation. Soon after most central banks around the world had an inflation target within their mandates. This didn’t happen until the 90s however, so bonds took a while to react as this consensus built.

It was this same consensus that eventually led to central banks thinking they could also defeat deflation, which resulted in ZIRP, which led to the losses bondholders (and central banks themselves) have worn.

This is the key to predicting whether we are in for another epic bond rally like that which started in the 80s. Will central banks cut to zero again?

Are the days of ZIRP over for the Fed?

In response to the debt overhang that encouraged the GFC, the Fed moved to ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) after Lehman Brothers collapsed. It maintained this position for 7 years until Janet Yellen hiked away from zero rates in 2015.

I have said repeatedly that the prospect of another unexpected jump in inflation is very unlikely, but that persistently sticky core inflation between 3-4% (with panic at the higher end of that band) testing the Fed’s resolve.

Political norms are no more, so it is a fool’s errand to think that the Fed (or any other central bank) can’t cut to zero again with core inflation at 4%. Would this give us our bond rally? Probably not; the 10-year would continue to price in the corrosive effects of inflation on bond returns through higher nominal yields.

The only way we get a sustained bond rally is if both inflation falls below 2% (and the market believes it will stay there) and central banks cut with it. The second conditional outcome is more likely than the first occurring on its own, but it is non-zero while China is exporting deflation like it is, even if that force is up against services inflation which continues to be a problem.

The politics will ultimately determine destiny here. If there is a willingness to repair the twin-deficit imbalances, then the environment for a monster-rally will arrive. The politics is a million miles away from this being a possibility.

The politics is almost permanently stuck in “muddle-through” state. Changes and reform are becoming impossible, if they aren’t already. Populism means that there will be a push from both sides to keep interest rates low.

This puts us back in the loving arms of the yield curve steepener.

The only real critique I read about the steepener trade is that it is the consensus trade.

Adherence to this sort of thinking would imply that trend isn’t a reliable factor in attributing market returns - but it clearly is.

The consensus trade in bond markets since around 2008 was that there was never any point in shorting bonds. This was a heavy consensus trade, with several slogan emerging from the period such as “buy bonds, wear diamonds” (a saying I find a little cringe to be honest).

The “everyone likes steepeners” of today is the “everyone likes bond longs” of the 2010s. The themes attacked in this newsletter are the real underlying force for this view and are ultimately driven by the general belief that fiscal austerity no longer suits the objectives of most western states.

The steepener requires on-hold or easing central banks. Is this not just a repeat of Arthur Burns?

I believe Arthur Burns had a principled (if not ideological) viewpoint on why he didn’t intervene to position monetary policy in direct opposition to what the government had signalled it wanted by expanding fiscal policy as much as it did.

Governments can tax as they will. When the ability to tax runs up against the wall, the next best thing to do is to perform a soft default on your debt. There is no better way of doing this than to cause inflation, even if interest rates go up to compensate for the inflation the government caused by its spending.

Low rates and high inflation create rolling soft defaults, where real returns on bonds are perpetually negative. The market’s only way to protest this outcome is to buy assets that benefit from negative real interest rates.

While I’m confident in the floor on 10-year yields, I am also confident that bond markets won’t become unhinged because of loosening views on inflation control. Cancelling bond buying is almost impossible, both domestically and from abroad, while China’s push to deflate goods prices can’t end for similar reasons.

It is a hopelessly poor equilibrium to be stuck at.

Ignore the clickbait

Whenever you see the articles that predict a crash in government bonds or reveal how the market for Treasuries will suddenly crack, please don’t click on them.

Apart from most of these articles being factually incorrect about the mechanics of government bond markets, they miss three important facts.

The first is that government bond markets have become far more crucial to the functioning of the entire financial system in recent years. This isn’t only because of its size (this is also important), but its elevation as the default form of collateral for nearly everything due to changing regulation means that it can’t do anything but be saved.

The second regards central bank independence. Independent or not, they don’t care for bond holders either way. Rates will never be high enough to compensate for the threat of higher inflation. Central banks facilitate losses during inflationary episodes.

The third is that they’ve missed the boat and its already happened. This is the key point of this newsletter.

Spending too much led to inflation which led to deeply negative real returns. These real returns were so negative in fact that bond and cash holders experienced real returns that were even worse than that of the 70s crisis.

For those that owned these assets, they indisputably got poorer. They got poorer just like a bond holder of Lehman Brothers or Countrywide or Ford. They just might not have realised it.

The forward estimate of inflation for used to determine forward real returns until 2032 is 2.7%. Note that even if inflation were to get to 2% by 2027, both the worst and average real returns would still be worse than the 1970s as ZIRP in the 2010s (for which we do have the inflation outcomes to know total real returns for certain).

A static 2.7% inflation rate is fair given the Fed’s relative comfort with inflation at about 3%, and the historical relationship that inflation trends tend to be the best forecast of future inflation.

I love your work, Peter. The next natural question for me is: how does this whole analysis reconcile with long-term inflation breakevens being where they currently are (10Y 2.25%, 30Y 2.18% in US TIPS, almost identical in Australia)? The nominal yield curve steepener does make sense, macro-economically speaking, but why is the term premium entirely embedded in the real yield component, while the implied inflation term structure is not just very low but actually downward-sloping? If soft default via inflation is the way out of the debt spiral, shouldn’t it be the other way around? For me, this is the most inexplicable conundrum in current macro, and I’d very much appreciate your thoughts on it.

https://fraser.stlouisfed.org/files/docs/publications/FRB/pages/1985-1989/32252_1985-1989.pdf