The (small) bank conundrum

The conundrum is not in what small banks should do, but what policy makers should do with small banks

The commercial bank is at the core of the modern financial and monetary system. There is no doubt that they are incredibly important to the continuation of our economy as it is, and is why bank-led crises are so worrisome.

The recent small bank crisis highlights that the institutions with this important role are also the most fragile.

Banks accept mostly on-call deposits to, in turn, lend to customers over the long-term. This mismatch, along with high leverage, is inherent in the basic operation of a bank. These two factors mean that banks require the unwavering confidence of those they deal with.

Traditionally, a loss in confidence manifests itself as a run on deposits, which is fatal whether the bank is fundamentally healthy or not.

Once a bank run starts, nothing can be done to stop it outside of emergency help from the central bank acting as the lender of last resort.

The US small bank crisis of 2023 brought the reality of this inherent fragility front and centre. Bank runs started because of the fear of losses associated with large holdings of US Treasury bonds. These securities fell in value because of rising interest rates.

Some of the blame for the underlying issues lie with choices made by individual banks. I will make an argument that they were set up for failure by the government, and the Fed.

Either way, policy makers have some difficult decisions to make about the future of small banks in the US, which will become more apparent as this slow motion crisis continues.

What a bank needs to do

Banks issue loans to monetise assets (or an individual’s future earning capability) and, in turn, create deposits. For this they earn a margin over their cost of funds, summarised as the “Net Interest Margin” (NIM), which is the main form of profit equity owners of lending banks get for taking on the litany of risks associated with banking.

To collect the NIM, banks perform 3 main functions:

Evaluate credit risk of their lending well and keep sufficient capital against this risk;

Manage interest rate risk of their balance sheet; and

Keep their long-term assets funded.

The expertise that banks have in determining credit risk is amongst their primary functions and is the main determinant of their long-term profitability. Banks hire credit risk managers to determine what lending is safe, with oversight from the regulator.

The next two points are intertwined and complex. These 2 functions are handled by the treasury department of the bank, and in bigger banks this is tied in with the trading and market-making departments as well.

How banks fail

A failure of a bank is easy to visualise in the case were they evaluate credit risk poorly. I covered this in my last newsletter, outlining the death spiral that a bank (and the broader economy) will fall into if there is a wholesale loss of confidence in the ability of banks to have evaluated credit risk properly.

If credit losses are big enough, a bank will burn through its loss-absorbing capital, leaving it in a position where it must urgently raise capital to cover any future losses. The banking crisis of 2008 was so damaging precisely because these credit losses were compounding so quickly.

Losses stemming from bad lending have been curiously missing in the bank panic of 2023. It is instead the management of interest rate risk and funding risk which has (supposedly) caused the bank runs that brought down Silicon Valley (SVB), Silvergate, Signature and First Republic Banks.

I say “supposedly” because it is impossible for any bank to eliminate interest rate and funding risks. SVB started the crisis because its approach to interest rate risk was ‘cavalier’, in the context of having nearly 75% of their balance sheet in long duration securities.

Banks that are currently experiencing trouble, such as PacWest Bancorp, don’t suffer to the same extent in terms of deficiencies in interest rate management. They do, however, have a large amount of securities on their balance sheets, something we’ve seen before.

Securities versus loans: 2008 redux

The GFC had exceptionally bad lending occurring in one particularly risky niche, that being sub-prime residential mortgages.

Ben Bernanke himself was fooled by the niche nature of this lending when he declared that the crisis was “limited” in one of the worst financial calls in modern history.

Given the fundamental factors in place that should support the demand for housing, we believe the effect of the troubles in the subprime sector on the broader housing market will likely be limited

Jokes aside, his analysis wasn’t strictly wrong. Sub-prime represented a small proportion of total mortgage lending1. What he missed was that any illiquid market (such as housing) that experiences even a small amount of co-ordinated selling would domino into a crisis that infects even prudent lending.

However, this explanation doesn’t really capture the way in which the sub-prime crisis caused such widespread issues in the US banking system.

An important factor contributing to the wildfire was that mortgages tended to be securitised, being packaged up and sold, and being able to find their way throughout the system. These packages were then given credit ratings that were so incredible divorced from their underlying risk that it caused the wrong people to hold them, with the wrong amount of capital held against this risk. These factors combined to exponentially increase risk, and therefore subsequent losses.

These securities also spawned derivatives that were designed, ironically, to help to manage risk. These derivatives, however, ended up becoming the basis of more securities, extending the reach of sub-prime. Risks were replicated and leveraged until a niche form of lending ended up having a massive footprint across the financial system.

Write-downs of the lower tranches of securitisations sparked the GFC. If this same lending was more direct in the form of loans, banks would have had far more control over how and when losses are recognised (within the regulatory framework of course) rather than being at the whim of a traded price resulting from an illiquid market in those securities.

If traders can see that the prices for these type of securities are plummeting, then it is easy to extrapolate this across similar securities and identify the banks that hold those securities.

Swift price markdowns caused confidence in the banking system to disappear almost overnight. Bank equity prices slumped, and bank runs started.

Bank runs kill banks because no risk management can help you once it starts. The only solution is to go cap in hand to the central bank to provide emergency liquidity to fill the gap after it happens.

Today, small banks with large securities portfolios have been targeted by short-sellers which encourages deposit flight and emboldens more short-sellers (and so on). Once the spiral starts, it is hard to stop.

This time around the securities are government securities, not credit risk laden securitisations like in 2008. Their price has fallen because of a steepening yield curve arising from accelerating inflation and a Fed that has reacted to that by hiking rates, and not a fall in credit quality.

It may not be credit risk causing the fall in price for these securities, but that doesn’t really matter.

Despite these banks not having to mark these securities to market by defining them in an accounting sense as “hold-to-maturity” assets, the market has assigned losses on these securities as if they had to be sold today.

These securities were “hold-to-maturity” until a worry about their how they were funded made them not. Funding problems made forced the reality of mark-to-market losses, which created more funding problems through fleeing deposits.

This is a contingent risk that is impossible to assign a probability to.

The irony is that interest rate exposure has hurt the entirety of every bank’s balance sheets, not just securities. Banks lend long and borrow short as a matter of course. Like the GFC, however, it was revaluation of securities and the transparency inherent in this that caused the run to happen.

Why has this only affected small banks?

There are several key reasons for why small banks have borne the brunt of a repricing of interest rates, despite it the core of the issue affecting all banks equally.

Securities are concentrated at small banks

The enormous issuance of government securities to fund pandemic era handouts created deposits and securities which were created and absorbed by the banking system.

Deposit growth has been homogenous across small and large banks, growing about 40% over the pandemic. Some banks (such as SVB) attracted greater growth.

The lack of lending opportunities meant that small banks had to increase their securities portfolios greatly to invest these deposits, and this has led to the biggest bifurcation.

The Treasury and Agency securities portfolios of small banks increased from $500b to $820bn at its high, representing a near 60% increase in the size of these portfolios. The increase was nowhere near as bad for large banks, maybe due to better lending opportunities being available to invest the increased deposits into, or the ability to retire other forms of funding instead. The government security portfolio at large banks increased by 36%, matching the increase in their deposits over this period.

Small banks found their balance sheets moving more towards securities. Banks like SVB had endless deposit growth and changed from a bank into something more similar to a government bond mutual fund in barely a year.

SVB could have avoided the problem by rejecting deposits. Deposits (especially after the GFC) are seen as the best form of funding, and if you are being offered zero-cost funding to increase the size of your bank and its revenue, why would you say no?

The focus on securities happened while small banks’ balance sheets were full of them.

Small banks are less able to deal with the problem

Large banks, unsurprisingly, benefit directly from being large. It is harder to short-sell their stock and have a meaningful effect on their price, where small banks with a smaller market cap will be easier to drive lower.

If deposits start to flow out of larger banks, they also have more options in being able to replace that funding due to superior access to wholesale funding markets, and a more diverse security and syndicated loan portfolio they can sell to fund any deposit outflows.

If the deposit outflow crisis was more evenly spread amongst small and large banks, it would still be large banks that would benefit. Deposit accounts are a utility, and can’t be replaced outside the banking system. This will naturally cause flow towards large banks in a normal crisis.

Where small banks made mistakes

Once you actually think your way through the problem you realise that so much has coincided to set up small banks for failure.

It is easy to blame the banks themselves. They were the ones that chose to take deposits, to buy securities, and not to hedge. They hid behind the veil of “hold-to-maturity” accounting as their securities portfolios became a massive part of their balance sheets, hoping to never have to sell these securities.

They accepted deposits while ignoring any possible risk that those deposits weren’t permanent. The analysis (especially in SVB’s case) on the relative stickiness of deposits was sorely lacking.

Misjudging deposit stickiness is the main error here, and not interest rate hedging. Small banks took on a huge amount of uninsured deposits to rapidly expand their balance sheets for their own future profit.

Rapidly expanding balance sheets are the number 1 predictor of future bank failures. This rule has held true over decades, and was generally ignored this time around because of the nature of the balance sheet expansions (deposits and “money good” Treasuries).

Laying blame on banks alone ignores ham-fisted regulatory changes, irresponsible government deficits and a contradictory Fed have a lot to say for this situation.

How is the government at fault?

You can summarise regulatory changes since the GFC in one sentence:

Deposits good, government bonds good, everything else bad.

This attitude was taken from what worked during the GFC, namely those banks that weren’t exposed to wholesale funding and had a large part of their portfolios in government securities did better than those that did not.

“Past performance isn’t an indication of future returns” is something that regulators should probably take into account as well.

These regulations have encouraged banks to optimise for them, happily taking on risk in government securities. The government has benefitted from this directly by allowing it to issue incredible amount of debt and have the banking sector readily absorb it.

The deluge of deposits that filled the system as a result of government spending overwhelmed banks, with small banks struggling the most.

More debt increases fragility in the system. It doesn’t matter if this debt is perceived to be the safest out there – increasing leverage too fast is usually deadly. The government increased debt at one of the fastest paces in history.

The Fed has also had a hand in this crisis, both in approving the rules by which regulation changed, and then trying to fix the consequences of this with a big balance sheet.

The hypocrites at the Federal Reserve

On the surface it may seem that the Fed is doing everything it can to support small banks during this difficult time.

In response to the spreading contagion, the Fed has offered liquidity support through its Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), and through the regular discount window.

The BTFP lent to banks for a term of a year, being able to use this funding to replace fleeing deposits. The genius of the program was that the collateral that needed to be pledged was government securities, with their collateral valued at par.

Valuing at par (as opposed to the discounted market values that caused the problem in the first place) dodges the hole-in-the-balance-sheet issue.

Previously the use of programs similar to the BTFP to patch over funding issues have traditionally resulted in stigma for the banks using them, highlighting that there is indeed a problem that has forced them to the Fed.

While the stigma isn’t as overt now as it used to be, it has caused the market to focus on the banks using these facilities in size.

So it may seem like the Fed is really trying to help banks out, right? On one side it is, but on the other it may have caused the issue in the first place.

The Fed as regulator has approved the move towards deposits and government securities through regulation. This has caused distortions that have resulted in the Fed being forced to run a huge balance sheet into perpetuity. I covered the reasons why in this newsletter.

While QE was partially the reason for such a large balance sheet, the main reason is the provision of Reverse Repos to Money Market Funds (MMFs).

Due to regulatory changes, MMFs were forced to purchase short-duration Treasury securities as short-term bank liabilities were disallowed. With less collateral available, MMFs would drive short-term interest rates below what the Fed intends, thwarting monetary policy.

The Fed’s RRP facility is effectively subsidising the headline yield earned on MMFs in the name of its own interest rate policy transmission, because of deficiencies due to regulatory changes.

The biggest consequence of this choice arises when monetary policy is being tightened, especially from a zero rate starting point. When rates increase meaningfully, the high yield of the MMF acts like a vacuum sucking bank deposits out of the system.

MMFs removing deposits from the system had a hand in starting the spiral. As deposit flow has continued towards MMFs, stress on the banking system has increased.

All of this is intimately linked, and they are all related to the preference for government and government-like securities from top to bottom. The Fed is forced to act hypocritically because it has regulated the system into a corner, and the government has lit the fuse by borrowing ~$7trn over the pandemic.

Pointing fingers is easier than finding a solution

The standard modern way out of a banking crisis is to use the perceived infinite size of the government balance sheet to buy your way out of it.

The form it takes this time is through expanding deposit insurance to all deposits, regardless of their size. This would reduce the impetus for a bank run, with the need to “shoot first and ask questions later” nature of panicking depositors would be reduced.

Will something like this stop the crisis? Perhaps not. Customer deposit preferences can still change no matter what insurance is available. If the policy change doesn’t stop it, then costs to the rest of the banking system (through fees) and to the taxpayer would increase.

A better question might be to ask “do we want to stop it?”.

Lawmakers should be balancing the cost of any program (including deposit insurance) with the benefit of keeping the culture of small banking in the US alive. Regional banks may provide more benefits than just those that are monetary, after all.

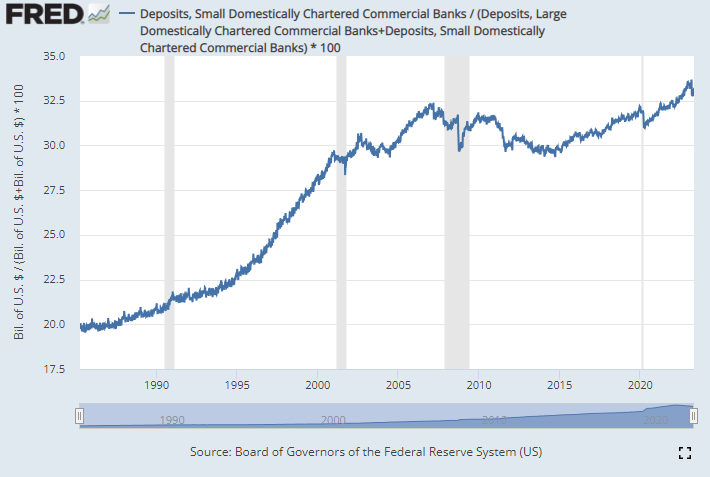

Having said this, small banks are currently an outsized share of the total system. This is incongruent with other developed countries where banking systems are typically dominated by a few systemically important banks that benefit from implied governmental support.

Spending more money supporting an outsized system might not be the best way forward. The right size for small banks might be somewhere in the range of 20-25%, rather than 30% as in the chart below. Small banks might be simply unable to compete in an era of a large Fed balance sheet and where government debt growth outstrips private loan growth by orders of magnitude.

While not entirely within their control, the confluence of issues which has put small banks in the US under pressure has brought upon a structural shift in banking since the GFC which was mostly due to regulatory changes.

I do not think we have seen the end of this shift as deposits continue to slowly flow out of small banks. However, I simultaneously think that it is not a big enough of a problem to cause a credit crunch. Macro effects should be limited as new loans and leases originated by small banks continues to grow.

Not recognising the structural shift that is the result of the advantage that large banks have been given through regulatory changes might be the wrong thing to do. Managing this transition slowly is better than disallowing it entirely through even more intervention, which is the very cause of it in the first place.

Policy makers should accept what regulatory changes have done and allow the market to adjust to it.

ARM sub-prime was only 6.8% of lending, while being >40% of foreclosures. https://web.archive.org/web/20080618024332/http://www.mbaa.org/NewsandMedia/PressCenter/58758.htm

Great article, as usual. Any thoughts on the possibility of narrow banks, or even tighter constructs and the FED's displeasure with such concepts?