Bad lending, financial crises and deep recessions

The roots of the classic financial crisis is in bad lending. What makes a bank-led crisis sufficient to send an economy into a coma?

Note: I wrote this newsletter before Silicon Valley Bank et al. failed, but have added a note about it at the end. As this Twitter thread highlights, I do not consider this failure one that is systemic and isn’t part of this analysis. I am sure you’ve all had enough of SVB already anyway.

A financial crisis is always underway when an economy experiences a deep and serious recession. A recession that is deep enough may cause a financial crisis – or a financial crisis may then cause a deep recession.

Causality is an argument that will always arise in these situations, and there may be some interplay between a recession and a financial crisis. However, in my mind it is clear.

An economy is far more susceptible to a freeze if the financial system is unable to supply credit on a rational basis. The “sudden stop” to the supply of credit to the economy makes every sector vulnerable, and magnifies the effect of a recessionary episode.

The presence of a serious financial crisis is the difference between a soft 2001 recession versus the devastation of 2008. This matters for 2023.

A technical recession is near enough to a certainty over the next year. Knowing if a financial crisis is to occur is what will tip this soft recession into one that will make the Fed cut rates to zero again.

In this newsletter I’ll cover the types of financial crises that are caused by bad bank lending.

Knowing your lending types

The 2 broad categories of lending are secured and unsecured lending.

Unsecured lending is not tied to any particular asset, meaning that a bank has no direct asset to seize and sell if the loan goes bad. Consumer lending such as credit cards and personal loans fit into this category, along with unsecured corporate lending.

Secured lending is a much larger category of lending than unsecured. When a bank lends on a secured basis, it does it with a charge against an asset which it has control over in the case of default on the loan. The most significant segment of secured lending are residential mortgages, followed by commercial real estate lending, and then other sectors like secured corporate lending and auto loans.

Secured lending is safer for a bank and as a result it charges cheaper rates on this type of lending. The availability of collateral for a loan in the form of a physical asset allows a bank to realise the bulk of the loans value in the event of default in a much more efficient manner, with the valuation of that asset being easier for the bank to form a view on.

Secured lending dominates the supply of credit in a developed economy due to the inherent safety and link to cash flow production that security over an asset provides.

In the US, banks tend to carry a larger portion of unsecured loans due to the presence of the federal institutions which hold most residential mortgages, as well as the deeper and more sophisticated capital markets which allow for more securitisation in the US, taking loans off the balance sheets of the banks. Banks will hold securitised loans on their balance sheets as well, delivering a more leveraged exposure to the underlying loans.

The flavour of the crisis

Each US bank-led financial have been a result of a certain category of lending.

Working backwards:

2008 – Residential mortgages

1990s – Commercial real estate mortgages

1980s – Secured corporate lending

1930s – “Secured” margin lending

The first thing to note is that genuine financial crises are rare. Serious financial crises like the GFC or the great depression are 1 in 100-year events. Smaller crises happen more frequently, and tend to be localised. These occur once every 20 years or so. While I’m concentrating on the US here, other countries have experienced the same. The 90s saw crises in many developed countries including Japan, Australia, Finland, and Sweden. The echoes of the GFC saw banking issues across Europe.

There is a trend to notice here. Most crises are started by secured lending rather than unsecured lending. Banks also tend not to repeat the same mistakes, opting instead to find an new way to lose money in each crisis. This shows that regulations and behaviour has improved over time, with subsequent generations of bankers learning from the last. However, when they find a new segment to lose money in (such as subprime mortgage for example), there is almost no limit to how bad it can get.

The absence of unsecured loans is odd, as losses on unsecured loans are generally much higher. Why does secured lending create crises? To understand, we need to look at how banks take losses on loans.

How a bank loses money on a bad loan

A “net charge-off” event marks the point that the loss on a loan is recognised by a bank, after considering any recovery on a defaulted loan. This occurs after any collateral is sold, and a creditor has been through bankruptcy proceedings. This can take a long time. It is only after this process that the final loss on a loan can be accounted for.

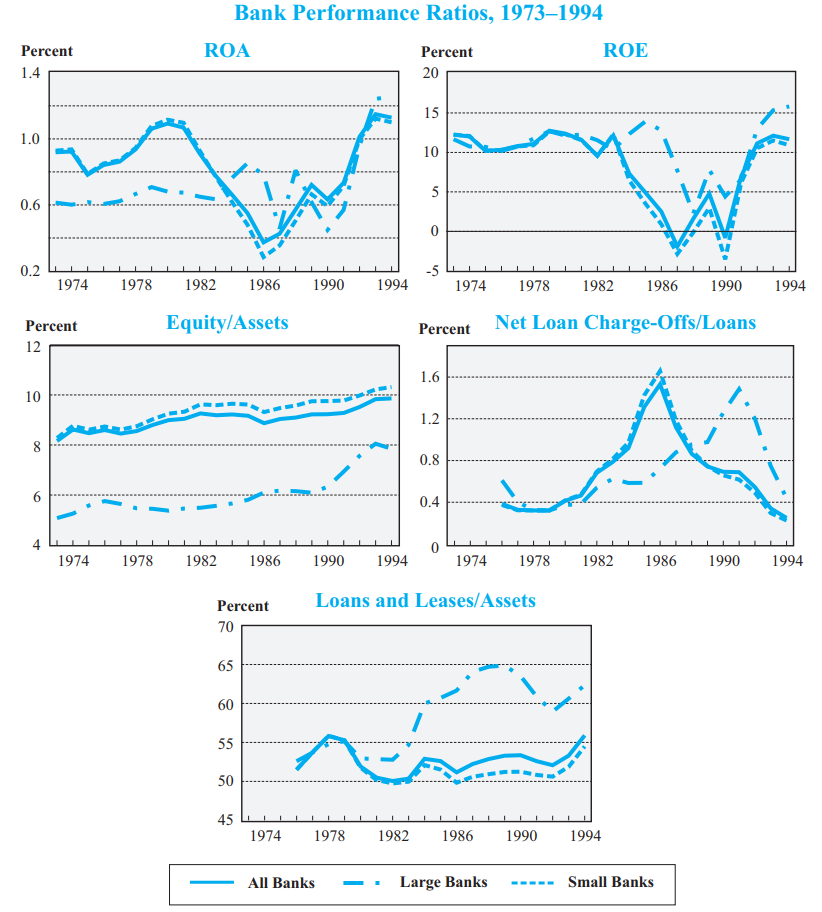

The chart above plots the charge-offs by lending type since the early 90s.

What is immediately apparent is how much banks lose on consumer debt, with credit card debt being the largest factor in this. Net charge-offs in credit card debt tends to vary between 4-5% of gross loan value outside of recessions, with this worsening depending on the scale of job losses in recessions.

The GFC saw a high of 10% charge-offs in credit cards. This may seem alarming, but when interest rates on credit card balances hover at about 20% most of the time this isn’t too shocking. Add to this the severity of the GFC and it only resulting in twice the charge-off rate of non-recessionary periods highlights why crises rarely arise from unsecured consumer lending.

This is despite the weighting of consumer lending sitting on the balance sheets of US banks being higher than most other countries, at about 25%.

C&I loans (or loans to commercial and industrial interests that are usually secured by collateral) have a lower charge-off rate than unsecured lending, as you would expect. They tend to rise from low levels in recessions, to maximum of about 2%. C&I lending makes up about 25% of total loans.

Finally, secured lending against property experiences a similar charge-off rate to C&I loans in recessions, with losses on residential mortgages being particularly painful in the GFC.

Unlike other types of lending, lending secured against property experiences the largest jump in charge-offs with virtually zero losses experienced during ‘normal’ times, expanding by 80 times non-recessionary rates in serious recessions!

Historically realised losses in residential mortgage lending were so low because of the conditional nature of secured lending. Not only do you need your borrower to default, but after that the value of the collateral (in this case a house) needs to also be less than the value of the mortgage. A loss is conditional on 2 events which were unrelated enough to not cause an issue.

It is the large change in expectation of losses, rather than the extent of losses themselves, which create a crisis.

The trigger – provisioning

As mentioned above, charge-offs take a long time to materialise due to the long time it takes to resolve a defaulted loan.

To ensure that banks are accounting for their possible future losses correctly, they are required to provision for expected losses. Once a charge-off is known, the provision is unwound and is replaced by a charge-off as the loan leaves the balance sheet.

This may be through tracking delinquent loans that are likely to default, and estimating a possible loss given default. Banking regulations also require banks to account for a general economic provision which buffers for losses as the general economic environment deteriorates.

Provisions for loan losses can accelerate quickly when a crisis is unfolding. This uncertainty and exponential degradation in bank profitability can create a panic, as we saw heading into the subprime crisis. The chart below shows provisioning across all US banks. Note that this is a quarterly number, so it is an increase the total amount of provisioning, rather than a figure of the total amount of loss buffer accumulated.

The seriousness of the subprime crisis can be seen in its full glory. The total amount of losses from loans added cumulatively to about 10% of total loans, and this doesn’t even include the losses from securities that banks held in the form of RMBS or CDOs that experienced heavy losses as well.

The cumulative provisioning chart below can help to visualise the size of each crisis relatively. Provisioning tracks a steady pace during non-recessionary times, with the slope increasing heavily during recessions. The steeper the slope, the more intense the crisis is.

The 80s and 90s had a longer lasting, but less intense crisis than the GFC. The 2001 recession hardly registered in comparison.

Interestingly, the onset of the pandemic led to an increase in provisioning which was subsequently reversed. The large government stimulus caused the banks to revise expected losses, resulting in profits being booked from an unwinding of provisions.

The pace at which a bank books provisions for loan losses is what precipitates a crisis – especially when it is sharp and exponential in nature.

How a crisis starts

There is a critical point that is passed when a regular decrease in credit becomes a crisis that is spiralling out of control.

That critical point is subjective, and is a function of the size of provisioning relative to the amount of capital a bank is currently carrying. From this point onwards it becomes a game of confidence. If provisioning for loan losses is large enough, the market might start to get worried about the amount of capital the bank has to absorb those losses.

At this point, if a bank attempts to raise more equity from the market to bolster loss-absorbing capital, it can stave off the worst of the crisis for a small while. A move like this is usually a double-edged sword, effectively telling the market that what we have might not be enough and there is worse to come, despite trying to do the right thing and shore-up their capital base.

These attempts are ultimately futile as loss expectations in the problematic asset class were just far too low before the crisis to not annihilate the banking systems capital many times over.

If loss realisation is 50-100x initial expectations, it is usually a foregone conclusion that some segments of the banking system will collapse, with a number of banks needing rescue or disappearing entirely.

The subprime crisis famously claimed a number of large banks. This crisis affected investment banks disproportionately due to the securitised nature of much of the problematic loans. This spread the crisis far wider than the traditional mortgage lenders.

The crisis of the 80s and 90s were split into two, with the first affecting small banks at the regional level, and large banks being affected in the early 90s. The regional crisis was caused by slowing state economies, challenges in numerous sectors and poorly run, under-capitalised banks.

This eventually carried over into the national level with overbuilding in commercial real estate leading to losses on mortgages. This is illustrated in the net charge-off chart earlier in this newsletter.

The number of bank failures at the regional level during the 80s was astounding. In some states, banks representing more than 20% of total assets went under, with some states such as Texas seeing banks representing 41% of banks assets (some $61bn) sink.

The chart above brings some questions, however. The 80s saw an incredible amount of bank failures, but it appears that recession caused bank failures, rather than the other way around. It was only the failure of large, nationally aligned banks that saw recession in the early 90s.

The Great Depression and the GFC also saw large bank failures, and this lead to very extreme economic outcomes.

As it turns out, bank failures are a necessary condition for severe recessions/depressions, but are not a sufficient condition. It really does depend on the size of the banking issue and its ability to cross-over from one sector and to the broader economy quickly.

Deep recession and the necessity of a financial crisis

A financial crisis of sufficient severity stops the flow of credit to the parts of the economy that aren’t impaired. This, in turn, impairs these previously healthy parts of the economy as well.

This creates a deep recession via two methods:

Corporates both healthy and unhealthy are unable to access credit at competitive pricing, putting businesses (and employers) under pressure. This causes a spike in unemployment; and

It synchronizes every sector of the economy to underperform at once. This causes a severe drop in confidence, leading to a sudden stop in consumption.

It is the sudden stop in consumption that makes a garden variety cyclical slowdown into a severe recession.

Consumption in a developed economy like the US is very stable, and grows in line with population and wage growth. Getting a outright drop in consumption (and as such have consumption detract from GDP), needs a serious event that suddenly and immediately damages household confidence. It’s very rare, as shown by the chart above.

The last recession to see a detraction from GDP by household consumption without a financial crisis was 1954. Each time before that, there was a financial (or monetary/inflationary) crisis that precipitated a decline in consumption. In a country with a growing population and positive rate of productivity, achieving negative consumption is extremely difficult.

The same argument holds sway for explaining why very large quarterly drawdowns in GDP are difficult in naturally occurring recessions.

A naturally occurring recession might be caused by a sector of the economy which has overheated, or has had demand issues either domestically or foreign sourced.

Generally, this sector of the economy will slow first. This will initially affect GDP directly, and if it is big enough to cause further issues, will slowly knock onto other sectors, and eventually onto consumption and employment.

This cascading form means that the individual cycles are “out of phase”, so by the time the first sector slows completely and affects the next, that first sector is no longer detracting from GDP anymore. It may not recover to positive growth, but the ability for that sector to detract any further is limited.

This is what leads to a gentle slowing of the economy, which eventually finds itself in recession without the pace of deterioration getting meaningfully worse. Interest rate cuts and fiscal stimulus help to reverse the trend which is at risk of being entrenched once confidence starts self-feeding and unemployment is bad enough.

A financial crisis sets off a circuit-breaker which inserts a cliff edge where there would have normally been a rolling hill.

A sudden stop to the flow of credit forces all sectors of the economy to rationalise immediately, for fear of a liquidity crisis ending their business. This alters the natural form of a recession.

Why didn’t the S&L crisis cause a depression?

Six of the top 10 biggest bank failures in the US occurred during the 80s and 90s (otherwise known as the Savings & Loan crisis). [Note that Silicon Valley Bank is in position #2 after its failure in March 2023]

While this list misses the notable failures of investment banks Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns (as well as lenders including Countrywide and CIT group) as they weren’t FDIC regulated “banks”, but this highlights why not every financial crisis is the same.

Despite the length of time and the impossible number of failures in the Savings & Loan crisis, the issue never managed to spill over into the greater economy in any major way until large scale commercial real estate was affected, when the larger national banks were implicated nearly a decade later.

Part of the reason for this is the FDIC’s proactive role in managing the failure of a lot of these banks. Depositors didn't lose money, and this stopped a contagion forming.

These banks were also primarily exposed to local markets, and were small enough that they didn’t have a way to leak contagion to other banks. The issues in Texas were due to weakness in the oil & gas sector, as well as local issues with property. Once banks failed here, there was no mechanism for panic to spread to other banks out of the state. This replicated itself across the country.

This is in comparison to the GFC where every bank globally was linked through cross-holdings of mortgage securities and interbank lending through short-term paper and long-term wholesale debt. Once confidence evaporated, it spread like wildfire from bank to bank. This left few sectors untouched when it came to a stop to the flow in credit.

Most importantly, most banks were taken over or saved through merger, it was the failure of Lehman Brothers with no regulator intervention in September 2008 which really co-ordinated the downturn and put an outright stop to economic activity. This effect was even more acute as it was a global event which further synchronised the economic cycles across country borders.

The Great Depression came about for a similar reason. Horrendously bad lending to vehicles that bought other equities on a levered basis and so on were a house of cards that was waiting to collapse. With no government help, the entire banking system, and thus the economy, collapsed.

The anatomy of a financial crisis

A financial crisis is a necessary condition for a serious recession. It needs to be the right type of financial crisis, though.

The financial crisis needs to be one that causes some sort of contagion, spreading from bank to bank in a way that forces a behavioural change in the way that they lend.

Once this contagion spreads, conditions are in place for a sudden stop in the economy that aligns the business cycles of affected and unaffected sectors. It also can align the economic cycles of different countries.

When it comes to spotting when a financial crisis is likely to occur, the knowledge that we uncovered earlier is useful.

A crisis always starts when provisioning for losses gets large enough to start worrying investors. A cycle this fast will generally only happen in regards to secured lending that has supposedly “safe” collateral attached to it, for it is in these circumstances that losses can far exceed what could possibly be expected.

It is only when nobody expects losses to come that they are large enough to do serious damage.

Nobody is surprised when losses come from unsecured lending, especially to the consumer.

Nobody is surprised when losses come from junk debt to sub-investment grade corporates.

It always comes in the form of lending which is deemed to be “safe”. This is the case every time.

Where has the lending been this cycle?

The current cycle has been extremely short. The third anniversary of the pandemic is only just upon us, far shorter than the usual cycle length of 6 to 10 years.

This means that it has been difficult for the private sector to amass any meaningful amount of debt. Property lending has picked up at a similar pace to what we saw prior to the GFC, but hasn’t happened for a long enough time to cause an issue.

Commercial real estate could face greater issues given persistent vacancy as a result of the pandemic, but overbuilding here hasn’t been an issue like in the past.

This all nets to a private credit growth number which has been stagnant at best over the last number of years. Total debt has grown over the period, however.

All of the debt growth that was required to support economies throughout the pandemic has accumulated on the public sector balance sheet. Government debt has grown faster than before any private sector debt crisis.

If a crisis is to appear, it is from government debt. These are rare in the developed world, but far more common elsewhere, with debt and currency crises being far more common than bank-led crises.

A truly unexpected crisis would come from developed market government debt.

Silicon Valley Bank failed in March 2023 when a bank run forced the realisation of losses on a large Treasury portfolio that was heavily underwater. In a way, the Silicon Valley Bank failure is a result of the surge in government debt. Record issuance of government debt caused deposits to be created in the economy, swelling bank balance sheets. The lack of private sector lending and an increase of deposits caused banks to buy increased US Treasury issuance to plug the gap in their assets from growing deposits.

Excess money and deposits caused by government debt issuance have given the banking system an overweight allocation to US Treasuries as in the chart above. It might be the first sign of the effects of the lockdown led bond issuance, with more unknown effects on the way.

Government debt crises are a different type of financial crisis, and this is something I will tackle in the next newsletter.

Great article! Thank you. If the excess this time is in the public debt market, as I believe you stated, then the private credit markets could be in danger. In other words how much will interest rates (10yearTreasury) have to rise to balance a large incoming deficit with a declining demand from big buyers(Japan,China Fed) which would contract private sector credit demand? Do you feel this will be the trigger that contracts credit throughout the system? It seems like it’s the public debt markets that are the threat? Your very helpful thoughts? Thank you:)

Great article. A little unclear as to why secured lending is more troublesome than unsecured.. very counterintuitive.