The Fed can’t shrink its balance sheet!

The Fed’s traditional role has been as the “lender-of-last-resort”. Since the GFC, it has been moonlighting as the “borrower-of-first-resort”.

Intentional bond buying and reserve creation through Quantitative Easing is only a small part of the reason that the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet is considerably larger than before the Global Financial Crisis.

Therefore the reverse process, Quantitative Tightening, can’t reduce the balance sheet by much either.

Understanding why the Fed’s balance sheet is so large requires analysis of the liabilities that are the mirror image of the asset side of the balance sheet.

These liabilities are unrelated to QE, and exist to maintain stability in the financial system due to the seismic shift in regulation and composition of the banking system.

These factors mean that the total possible contraction in the Fed’s balance sheet is only $800bn to $1.0trn, leading QT to end next year.

I can’t blame people who consternate over the role the increase in the Fed’s balance sheet has had on markets. They aren’t entirely wrong when they say the Fed is printing money, because it is; they aren’t incorrect when they think a $8.9trn balance sheet smells bad, because it does.

The devil, however, is in the detail. The Fed is creating money out of thin air; but it also takes money out of the system to compensate. A government entity having a balance sheet the size of most country’s GDP sounds like a bad thing; but they have to do it to satisfy post-GFC regulatory requirements.

QE was an extraordinary and possibly dangerous move for such a large central bank. But QE is only worth less than 10% of the Fed’s balance sheet as it stands today. The rest is a necessity of current banking regulations.

Whether this regulation was a good idea or not is considered later in this newsletter, and to be fair, deserves one of its own.

I have avoided going into the technicalities of the specific regulations here. I find that it makes explanations of the broader ideas behind these concepts harder to understand. Will there be changes to regulation that will reduce the dependence on the Fed to run such a large balance sheet? Probably, but it will not change the Fed’s new role of being “borrower of first resort”, a job that it assumed after the GFC nearly destroyed the US banking system.

A review of QE

As part of its mission to “normalise” monetary policy, the Fed progressively announced over 2022 that it would end the buying of Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) to satisfy the QE programme that started as a result of the pandemic. These adjustments would slow and then cease buying, followed by a controlled run-off (and possible sales) of Treasuries and MBS, to get the size of the balance sheet down.

QE was designed to further ease monetary policy when interest rates are already at the lower zero bound. An increase in bond buying is equivalent to lowering interest rates. A decrease in bond buying is equivalent to a hiking of interest rates. The total pace of buying isn’t as important as the relative change of it in terms of its stimulatory effect on the economy.

So, the Fed changes this policy by adjusting the rate of buying and selling. It does this by purchasing Treasuries and MBS from institutions that hold reserves at the Fed, creating money in those reserve accounts to compensate the commercial bank for the bond that it just purchased.

The “creating money” part of the above is what makes most people nervous about QE. Conjuring money out of thin air brings comparisons to the Weimar Republic and Zimbabwe. What makes the US different from those places is that for every Dollar “printed”, it buys something else that’s as close as you can get to a Dollar, a US Treasury bond.

The bond that is bought with the newly printed US Dollars buys some other US Dollars and locks them up on the Fed balance sheet. That’s it. For a bank, the bonds that it has given up as a result of QE were easily convertible into Dollars if that’s what they wanted, so it makes barely any difference to the bank’s ability to create credit.

The limit that dictates whether a commercial bank can lend more is the amount of regulatory capital it has to back new lending. Whether the bank is holding Treasuries or reserves at the Fed is of no consequence if it wanted to lend more.

QE takes interest rate risk out of the market. It buys bonds and takes the mark-to-market risk of those bonds, paying the Fed rate in return on the balances created. This, in theory, crowds out risk-takers and forces them into securities or projects higher up the risk spectrum, which eases monetary conditions in the economy.

Did this work at all? I don’t know, and I don’t think anyone would ever know without jumping in a time machine and seeing what would’ve happened if QE never existed. It seems that European yields were suppressed to lower levels far more effectively from ECB QE than they were in the States by Fed QE, but inflation and growth were lower too. Adding to the confusion is that increasing bond buying has, time and time again, resulted in the yield curve steepening, while ceasing bond buying has always led to curve flattening. This is not the relationship you would expect.

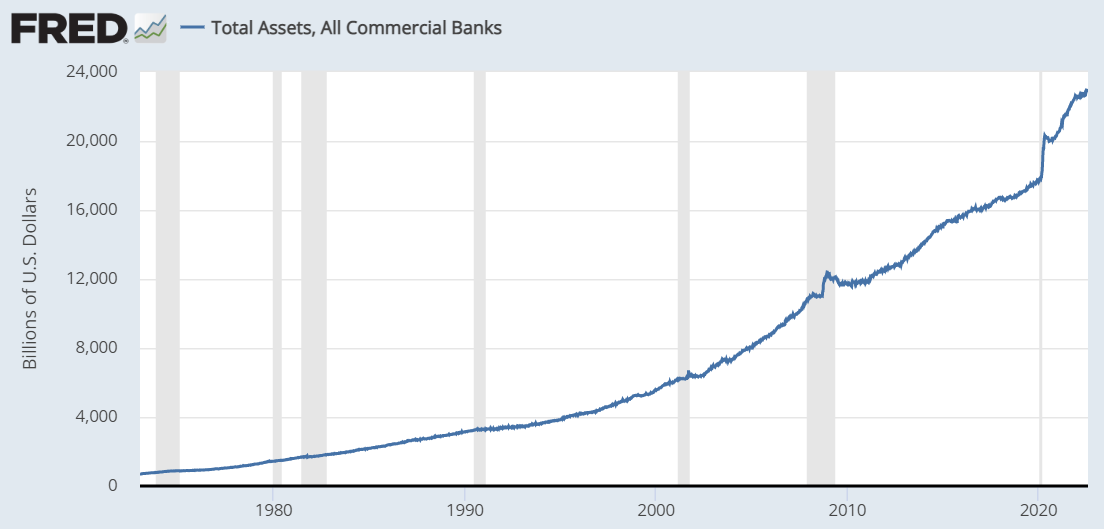

Over successive bouts of QE, the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet has grown from $1trn in the period before the GFC to $8.9trn at the time of writing. This is only $90bn off the absolute high recorded earlier this year.

Ending bond buying

The ramp-up in bond buying eased monetary policy. When the point in time came to starting tightening monetary policy, the pace of bond buying reduced, a process that the Fed calls “tapering”. Semantics aside, it is in this process that the Fed slows the accumulation of Treasuries, and as such slows the growth in its balance sheet.

As tightening continues, the amount of bond buying won’t cover the natural path of maturities of the bonds already on the balance sheet. As maturities start exceeding purchases, then the Fed has entered what it calls “Quantitative Tightening”, which is what they refer to as the state in which the Fed’s balance sheet contracts.

The Fed are targeting a reduction of in the balance sheet by $45bn a month, which will be increasing to $95bn in September. This is double the pace the last time QT was tried in 2017, and ended to some disaster in 2019.

Reducing the balance sheet back to $1trn from $8.9trn at a pace of $100bn a month would take roughly 6 and a half years. On the face of it, returning the balance sheet back to pre-GFC levels is impossible unless contraction increased to greater than $300bn/month.

If the Fed wanted to do this, could it? The answer is no.

Understanding a bank’s balance sheet

To get to the bottom of how the asset side of the Fed’s balance sheet got so large, we need to understand how the balance sheet of a typical financial institution works. The Fed isn’t that different from a commercial bank in how it accounts for its lending and borrowing.

For any commercial bank, assets must equal liabilities plus equity. This is an accounting identity.

Bank of America’s balance sheet for the end of 2021 had $3.2trn in assets, $2.9trn in liabilities and $0.3trn in equity.

The majority of the assets are securities and lending, with a large allocation to cash. This is no different to the Fed; it holds nearly all of its assets in securities (specifically Treasuries and MBS). Ultimately, securities are another form of lending. Buying a Treasury is no different conceptually than lending the US Treasury funds directly.

Bank of America’s liabilities and equity fund the purchase of these assets. The strong majority of this funding comes from customer deposits, which spans retail and commercial clients. Two-thirds of assets are funded with deposits which are preferred as they are sticky, and low-cost. There has been a distinct shift towards deposits since the GFC.

The rest of the assets are funded from other sources such as long-term debt where Bank of America sells bonds to mutual funds, and entering into repurchase agreements, where the bank borrows money using its best securities (Treasuries) as backing for the borrowing. The former is far more expensive than the latter as a form of funding.

Repurchase agreements, otherwise known as “repo”, sounds like complicated financial system plumbing instrument, but they really aren’t that hard to understand.

A party entering into a repo is borrowing cash over a short-term window (typically overnight to a couple of weeks) and providing security in return for that borrowing, with the most common type of collateral being a Treasury bond. The party borrowing cash sells the Treasury and simultaneously agrees to buy it back in the future at a slightly higher price (with the difference being the interest on the ‘loan’).

Finally, the equity portion of a bank’s balance sheet is made up mostly of retained earnings (or at least you’d hope so). Retained earnings increase equity when a bank makes a profit, and reduce it when it pays dividends. This portion of the balance sheet is heavily regulated as it is the portion that absorbs losses first. The amount of equity has in the true constraint to how big a bank’s assets can get.

[Watch for a part 2 to this newsletter, explaining the central bank’s equity and whether it can go into negative equity.]

The Federal Reserve is also a bank, and as a result also has a similar balance sheet.

The Fed’s balance sheet

We’ve covered the asset side, which is what most concentrate on. Let’s have a look at the other side of the balance sheet as it will answer the question about what funds the purchase of those $8.9trn of assets.

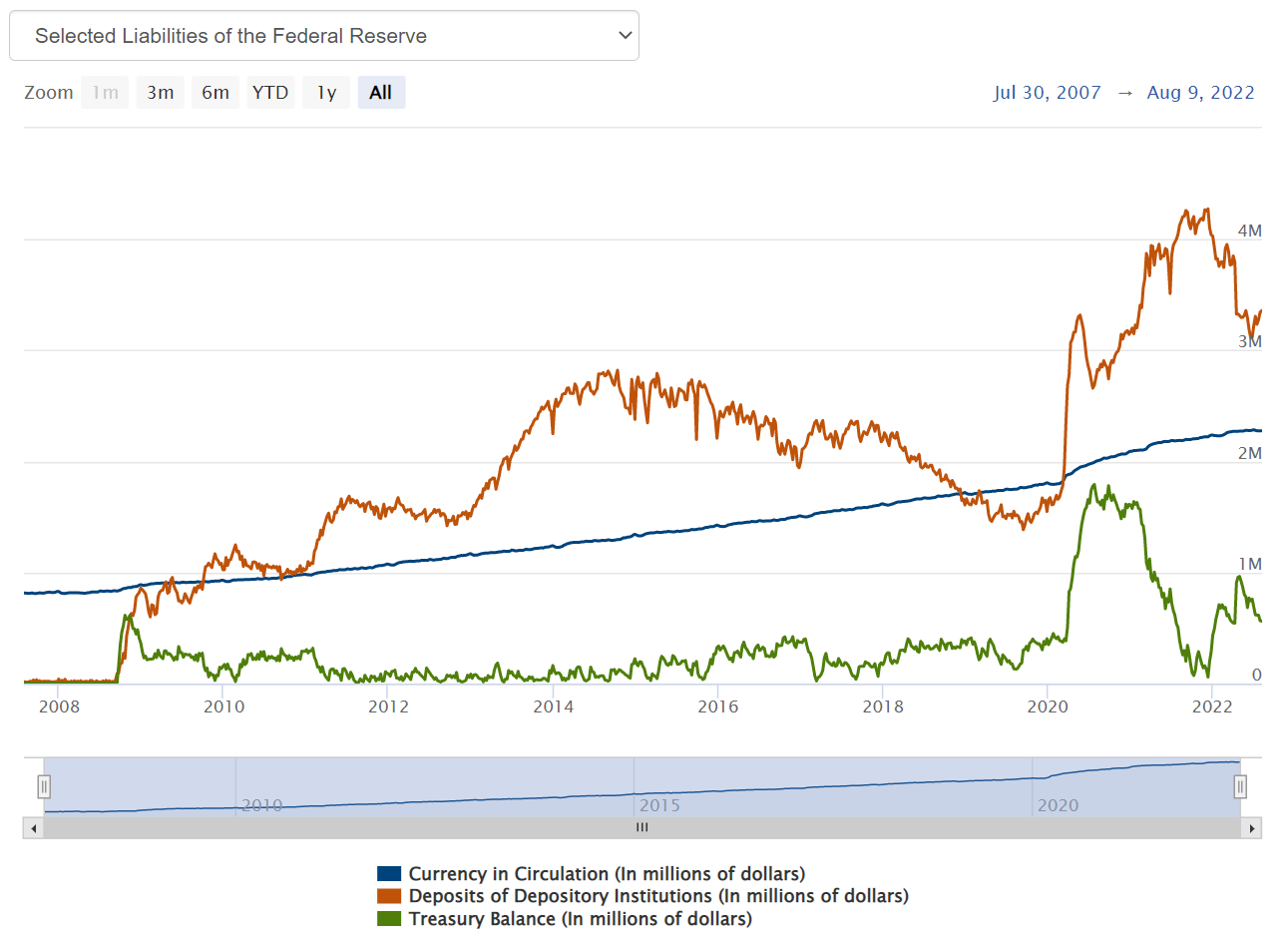

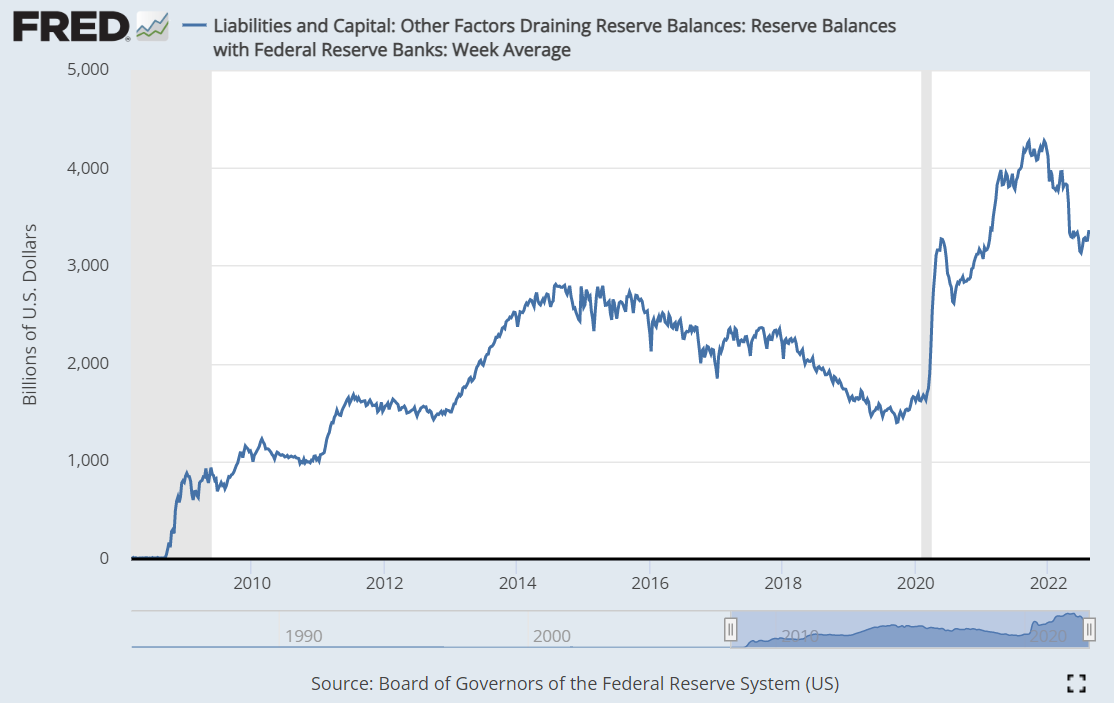

The chart above illustrates some of the major liabilities and how they’ve changed through time.

Currency in circulation

The first is “currency in circulation”. When the Fed prints money (and by that I mean literally prints physical cash you put in your wallet), it sells them into the banking system who “buys” the physical cash from the Fed and then the Fed purchases securities with the payment. By following this process the Fed avoids debasing the currency as it takes money-like instruments (Treasuries) out of the system in return for putting physical cash in.

Currency in circulation was the only major liability of the Fed before the GFC at $0.8trn, and it funded the entire balance sheet. Today, currency in circulation is $2.3trn.

This non-cancellable balance of physical currency at $2.3trn is a large chunk of the $8.9trn assets. This amount can’t be reduced through QT, so this amount sets the minimum floor for the size of the Fed’s balance sheet.

Treasury Balance

The next liability to consider is “Treasury Balance” or the deposit that the US Treasury keeps in the bank to pay invoices for government services. It is volatile, reflecting the mismatch of tax receipts against spending and bond sales. The balance currently sits at $0.7trn.

The Treasury balance clearly isn’t in the Fed’s control, as they are just providing a service the US Treasury, like a commercial bank does when it accepts deposits. Something must be done with this money, and in the Fed’s case it’s invested back into Treasuries.

Like with currency in circulation, the US Treasuries balance at the Fed in unaffected by QT. Adding this to currency in circulation lifts the minimum size of the Fed’s balance sheet to $3trn, already over 3 times what it was pre-GFC.

Bank Reserves

The final element on the liabilities chart above is “Deposits of Depository Institutions”, otherwise known as bank reserves. This is the money held at the Fed by commercial banks and other institutions including GSEs such a Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae. This currently sits at $3.3trn.

When the Fed conducts QE, the bank’s reserve account is credited in exchange for that bank selling a Treasury security back to the Fed. The process of electronically increasing a balance in these accounts is for all intents and purposes “money printing”, as it is created out of thin air with a few keystrokes. This creation increases the size of reserves, and we’ve seen these increase through every bout of QE.

Reserves should decrease during QT, as it is just this process in reverse. The Fed sells or matures off its Treasury holdings, and reduces the counterparty bank’s reserve account in kind.

Bank reserves are one of the liabilities on the Fed’s balance sheet that it does have control over through QE and QT. It could feasibly guide these balances back to zero through the QT process. Why it can’t will be revealed later in this newsletter.

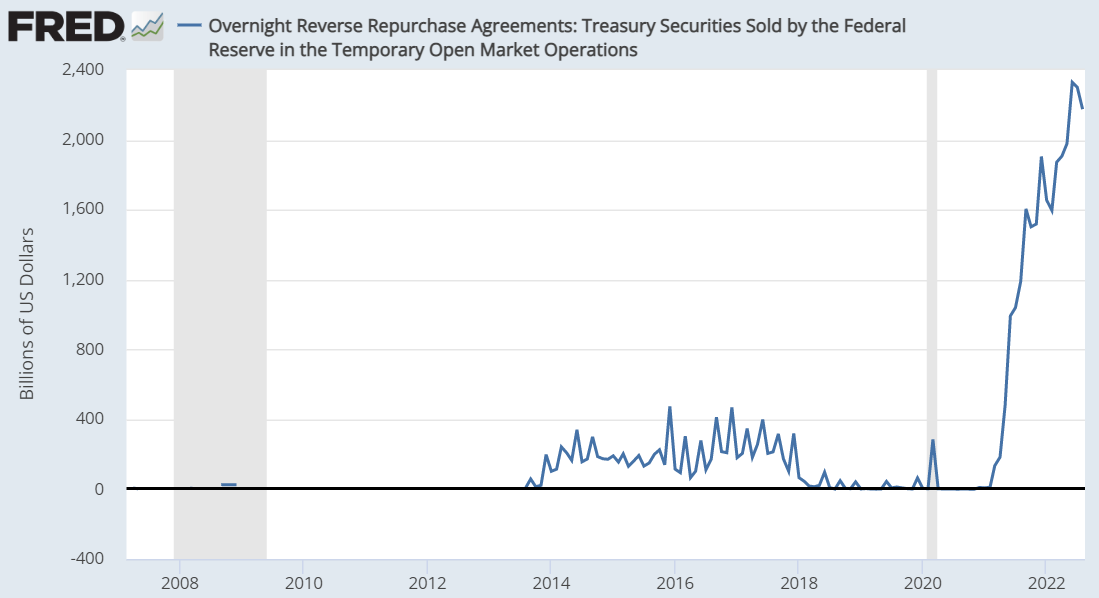

Reverse Repo

The sum of these three elements above is $6.3trn, which is still short of the $8.9trn that the asset side of the balance sheet describes. The final element is charted below.

In the same way that the Bank of America uses repo to fund its assets, the Fed does the same (although it calls them reverse repo as it considers it from the counterparty’s perspective just to make things confusing). These now total $2.2trn to make up most of the gap left to $8.9trn.

Reverse repo is offered to the market to fulfil its need for short-term, high-quality, “safe” assets. They are an asset for the system because they are a liability for the Fed. They are not affected by QE or QT, however other decisions that the Fed makes contribute greatly to the degree of the use of these facilities.

These four components are the major building blocks of the Fed’s balance sheet. Only bank reserves are directly affected by QE, representing 37% of the Fed’s assets. This sets the smallest possible balance sheet size given today’s dynamics at $5.6trn, significantly larger than before the GFC.

$5.6trn is still smaller the where the balance sheet can go in practice, however.

Can bank reserves go to zero?

Before the financial crisis, the Fed did not pay interest on excess reserves (IOER). As a result, commercial banks chose to do other things with that money.

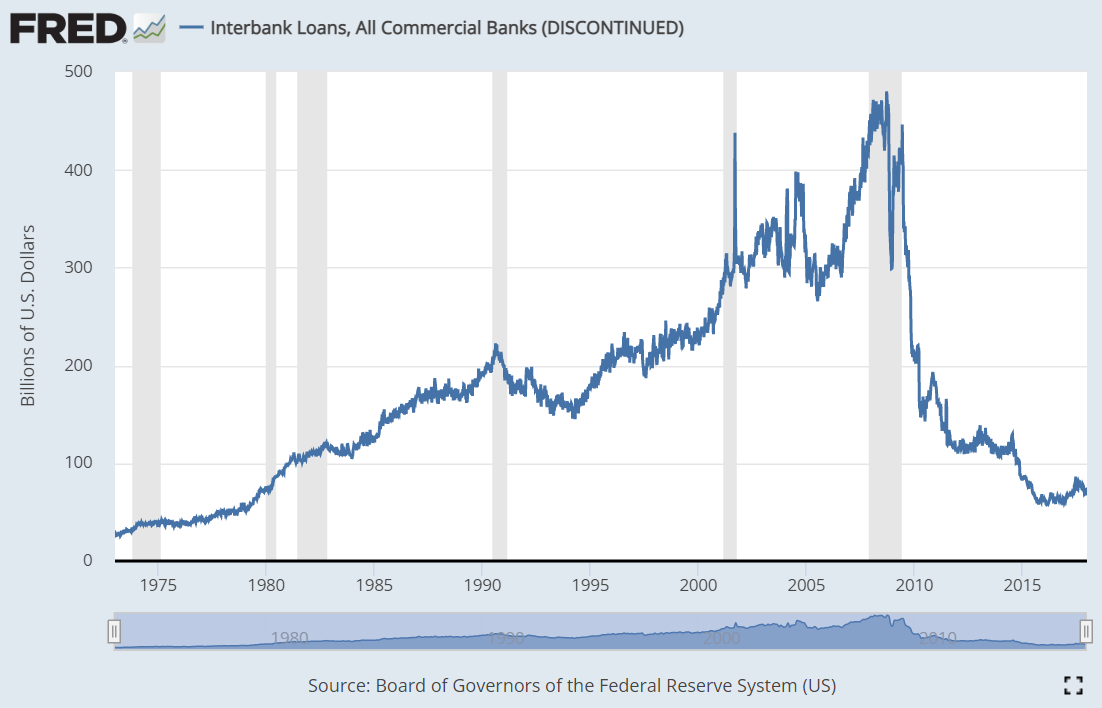

In the years before the GFC there was no shortage of new and “innovative” things to do with that money, even with the constraint of it having to be short-term and highly rated by the credit ratings agencies. This lead to an explosion in interbank lending and short-term lending to off-balance sheet securitised assets in the form of ABCP (Asset Backed Commercial Paper), an important enabler of the housing crisis.

The chart above illustrates how important interbank lending was in the growth of the financial system in from the ‘90s onwards. Today interbank lending is nothing but a shadow of its former self, and it’s not because the financial system shrunk in size after the GFC; in fact it continued to grow, albeit at a slower rate.

In this time commercial banks have also replaced interbank funding with deposits, further shrinking the possible market for these types of securities.

When the GFC hit and the real credit risk embedded in these instruments was revealed, the capital that previously chased short-term assets created by the financial system ended up being deposited at the Fed, helped greatly by the Fed starting to pay interest on excess reserves at this time.

This was a major shift in how the US financial system worked. Practically overnight, bank reserves grew to nearly $1trn.

This was the point at which the Federal Reserve added “borrower of first resort” as a role in addition to its more traditional role as “lender of last resort”. The fear and destruction of the GFC changed the collective behaviour of the banking system, and the Fed provided facilities as an escape to this.

After the initial shock of the GFC subsided, subsequent regulation changes over the last decade further changed where banks and money market funds (MMFs) could seek return on short-term investments. These changes as a whole can be summarised by two points:

An increase in the amount of government or government-like assets that financial institutions must hold; and

A reduction in the supply of assets that previously were appropriate to substitute government or government-like assets with, achieved by lowering or eliminating an allocation towards what used to be considered “safe” assets that were usually manufactured by the banking sector.

It’s not hard to see how these two factors working together will cause a shortage for the specific assets required. There just was not enough short-term government bonds (T-bills) to satisfy the requirements for commercial banks and MMFs.

As a result, the Fed stepped in to provide those government-like assets through reserves (which allowed commercial banks to be in compliance with new regulation) and repo (which made available sufficient assets for both banks and money market funds to remain invested).

Maintaining the availability of reserves and reverse repo now became a critical function of the Federal Reserve. If it decided to change pricing or to intentionally reduce the size of these facilities the financial system could seize.

The possible negative effects were realised in the repo crisis of September 2019. This severe market disruption set the practical minimum for bank reserves.

In September 2019 repo rates spiked, causing a short-term funding crisis for commercial banks. This occurred after the Fed reduced the size of its balance sheet during that episode of QT that started in October 2017.

QT caused a slow drain on bank reserves. When reserves hit $1.5trn, a funding crisis occurred and the Fed had to start expanding its balance sheet again. This, once again, grew reserves and averted the crisis.

The spike in funding rates was equivalent to a sharp tightening in monetary policy, and put the financial system at risk, with a default unlikely, but possible.

The Fed must manufacture assets

The two largest components of the Fed’s balance sheet – bank reserves and reverse repo – exist in the size they do because this new permanent base demand for short-term “safe” assets has been changed by regulation.

In effect, the Fed has forced regulation on banks and money market funds and has now had to provide assets to fulfil those orders. It has regulated itself into a new job that it cannot undo without reversing this regulation.

The Fed chooses to pay out favourable rates on the liabilities created for the purpose of “lubricating” the financial system and to avoid punishing the financial system for the regulatory changes.

It earns the money to pay these rates through the securities it purchases on the asset side of the balance sheet. It essentially takes the issuance of the government, mostly in term securities (the average maturity of Fed assets is around 7 years) and transforms them into short-term securities, warehousing the interest rate risk that the free market would normally take on.

This is of no consequence to the Fed, of course, as it has infinite ability to be able to take on this risk.

A big balance sheet is necessary for monetary policy to work

The 2019 repo crisis tightened financial conditions in an unwanted manner, far beyond what the Fed had intended through its deliberate policy shift over these years. This unintended change in monetary policy outside of the Fed’s desired range is the primary reason that the Fed’s balance sheet is as big as it is right now.

The argument up until this point is that QE has done little to increase the size of the Fed’s balance sheet, and therefore won’t be able to do much to reduce it. QE is essentially a red herring.

How about lowering the other components instead? Let’s say the Fed, in its attempt to shrink the balance sheet, set the rate on reverse repo to be below the lower target of the Fed Fund rate, or didn’t even offer the facility at all. Repo usage would decrease, and so would the balance sheet.

However, there would be a rush to buy the few qualifying assets available, driving down front-end rates to levels well below where the Fed is setting its policy rate. To compensate, the Fed would have to hike rates more to offset.

This means that a large balance sheet in the form of expanded bank reserves and large reverse repo books is to ensure that the Fed’s intended level for the Fed Funds rate makes it through to the real economy.

Leaving aside a crisis due to inadequate collateral, the Fed would have to hike its target rate by far more than it otherwise would if it didn’t act as the “borrower of first resort” for those institutions that it regulated into buying a very specific set of “safe” assets.

How far can QT go?

The September 2019 repo crisis guided towards a minimum amount of bank reserves at $1.5trn. In this time, financial system total assets has grown by a third, so this converts to $2trn in today’s terms.

Most analysts put the minimum in between $2trn and $2.5trn. Bank reserves are currently $3.3trn, so this means that QT can only occur for a maximum of 8-10 more months at $100bn in reserve shrink per month.

This means QT will be over in the first half of 2023, conveniently just after the market is pricing an end to the hiking cycle.

This will move the entire balance sheet from $8.9trn to about $8trn. At that point it can’t shrink anymore. This is news to most people.

There are temporary factors that exist outside of QT that may result in a smaller balance sheet. MMFs are particularly large users of reverse repo at the moment because we are in a hiking cycle and they want short-term assets to avoid locking in low rates for too long. This demand will dissipate as the Fed stops hiking, reducing the use of the reverse repo facility and causing the Fed’s balance sheet to shrink.

Additionally, if the US Treasury decides to shorten the average maturity of bonds on issue, it can create more collateral for the financial system, limiting the need to rely on repo. The trend in this has been in the other direction, however, as it has decided to lengthen maturities to capture lower rates.

The US Treasury should also draw down on its deposits throughout the year, causing its balance to drop towards the long-term average.

These more temporary elements aren’t going to change the main story for the size and composition of the Fed balance sheet, however. It also does not change the relevance of the intended contraction in the balance sheet. The effect of this will be short, and the pace of contraction will slow in a sooner time than most think.

Is there a long-term problem with the Fed playing this role? At a very high level the Fed is just being an extremely large bank and swapping long-term interest rate risk for short-term interest rate risk on behalf of the government. I don’t think there is inherently a problem with this, as the government could just do this itself by issuing more short-term debt to compensate.

The better question to ask might be: Was the cumulative regulation imposed on the banking sector since the GFC a problem? It’s tough to argue that these new regulations haven’t reduced risks in the banking system; but it has been at the possible cost of enabling (and even requiring) the government to heavily increase the amount of debt on issue. Despite stricter regulation, leverage in the economy has still increased, and simultaneously shifted toward the government. This sounds like regulation hasn’t reduced risks at all, just shifted them elsewhere.

This is a great piece. Thanks.

This is great, thank you.