Spiralling government debt isn’t a choice

There is little governments can do when the private sector decides to save, other than to spend itself.

Much blame is allocated to the government of the day for the almost exponential growth in government debt of western nations. This is despite the fact that we clearly vote for these policies, and these policies are so popular that both parties in two-party systems rarely stop each other from increasing deficits.

These policies are popular simply because the mathematics of maintaining historical growth means there is no other choice.

If the private sector makes the decision to “save” (or in economic parlance, be in surplus), then some other part of the economy needs to be in deficit to offset the gap in consumption or investment.

If another part of the economy refuses to be in deficit, then a foreign trading partner needs to be.

If another trading partner won’t be in deficit, then a very painful deleveraging process begins.

Government can partially be the reason the private sector decides to save, but this doesn’t change the fact that if the private sector chooses not to consume or invest then the government must. There is no way around it.

Another economic relationship

The basis of this idea was that the requirement that trade must balance globally means that its identity, capital flows, must also balance. The flow of capital as a result of trade determines how debt accumulates in deficit countries and how potential bubbles can form.

If a country is in surplus (it produces more than it consumes at a country level), then the country “saves” by accumulating the debt of the countries it trades with by financing their excess consumption.

This same idea exists within a country as well.

Let’s say a country is externally balanced, in that it is running a current account balance that is roughly in line with nominal GDP growth. Let’s divide the economy into the usual categories of government, corporates and households.

Where there is an external balance, the sum of each category of an economy must also be in balance, otherwise the economy must adjust, either through activity or prices.

This means that if households are “saving” (they are producing more than they consume) then another segment, or combinations of segments must be in deficit otherwise the economy will adjust so that it finds balance, either decelerating or accelerating in nominal terms (which includes inflation as well).

This process also describes how a recession occurs and what are the key imbalances that occur to tip the economy over the edge.

It also explains the privilege that developed nations have in managing these sudden shocks. Their desirability as a borrower helps them manage sudden shifts in demand far better than small nations can. But this comes at a cost.

The Keynesian way

An imbalance caused by the private sector describes most recessions that occur in the developed world. Keynesian economic theory and its application aims to balance out a surplus in the household or corporate sectors by quickly increasing government demand.

Intervention by the government in this way helps to smooth out the volatility in the business cycle, preserving jobs, asset prices, and thus the banking system.

Keynes’ idea is predicated on the notion that this private sector surplus is temporary and due to a sudden lack of confidence. In these cases, any destruction to the productive base of an economy would be more costly than the debt the government might accumulate to provide a floor to an economy (I go through this argument in more detail here).

Not even during wartime, has there ever been a better example of this type of stimulus than during the pandemic. Government mandates shut down businesses and locked people at home, ensuring that the household sector was in an incredible surplus – work from home ensured that production continued while consumption was seriously hampered.

This explosion in the private sector surplus, left alone, would have been rectified by devastating job losses which would have eventually destroyed those jobs that continued as work from home. The economy would have had a sharp jolt lower in activity, finding a lower level of activity and staying there.

However, the government stepped in, more in some countries than others.

In the US, government made up for the fall in private sector demand (and thus it’s surplus) by borrowing and replacing it with a large government deficit. The cost of this was immense, but it allowed the US to return to a level of GDP that preceded the pandemic.

This represents a textbook application of Keynes’ theory. However, we face a different argument when a private sector is structural and continues for years, if not decades.

Who said we need debt to create economic growth?

Economic growth can broadly be broken down into 3 components: increase in working population, increase in the capital stock, and TFP (total factor productivity).

The third category total factor productivity, or TFP is the most important here (and one that needs its own newsletter).

TFP measures the increase in output of an economy from a fixed amount of labour and capital inputs. It will be higher for an economy which has a lot of “easy wins” in terms of increasing output, for instance urbanising a population or modernising its production.

TFP is long-term and thematic in nature. It is positively affected by new technology and negatively affected by overhangs which slow organic value creation such as burdens on business, commodity price inflation, or an overhang of debt.

The current estimate of TFP for the US is just above 1%, slowing from 1.5% in the 2000s. This picture is replicated across the developed world. True organic growth has been hard to find without any substantial productivity improvements.

At a 1% TFP growth level and population growth of 0.5% gives potential GDP growth of 1.5%. The CBO has a similar measure of potential growth.

In a recession, potential growth plunges and Keynesian stimulus papers over this plunge temporarily. Debt is used to do this.

However, debt can also used to keep actual GDP growth above potential growth over the long term.

Depending on what the proceeds of debt are spent on, they will have different multipliers in terms of their effect on economic activity, making outright attribution of actual versus potential growth due to debt difficult.

There is something that isn’t in dispute, however, and that is that outright deleveraging (in which debt-to-GDP decreases) will always lead to below trend growth.

De-leveraging is painful

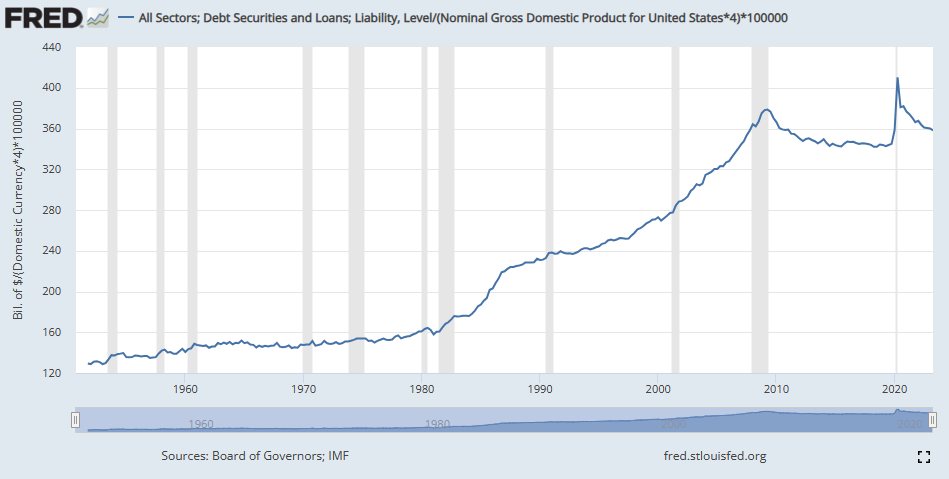

Decreases in total debt are extremely rare in the developed world. In the US since 1950, an outright decrease in absolute nominal total debt hasn’t happened outside of the GFC.

Expressed as a multiple of GDP the de-leveraging episodes are a little bit more frequent, occurring as the economy would emerge from a recession. Still-slow private borrowing would meet slowing public debt expansion as nominal GDP growth accelerates, lowering total debt-to-GDP.

Leaving the pandemic aside, the only extended period of de-leveraging has been in the post-GFC period. From mid-2009 onwards total debt-to-GDP declined from 370% to around 340%.

During this period, nominal GDP growth in the US underperformed the any other time in the post-war period. Nominal 5-year average GDP growth hit a measly 2.4% in 2013, 4 years after the de-leveraging process begun. The 5-year average is yet to surpass prior levels, although it will in 2025 if current nominal GDP growth figures continue.

The spike in total debt growth over the pandemic was one half of the driver of the growth cycle after the pandemic, with the other half being the contraction in the productive economy which manifested itself through inflation.

While the gap between potential and actual growth is difficult to explain perfectly with growth in debt, extremes in either direction lead to immediate effects on the economy.

The private sector makes the call

Post-GFC de-leveraging in the US happened because the private sector decided to do so1. The chart below shows the public sector versus private sector debt as a percentage of GDP.

The de-leveraging in the private sector was notable, totalling near 50% of GDP. Government debt made up for some of this retracement, but expansion of public debt wasn’t sufficient to make up for the contraction in private debt. As a result, the economy underperformed, initially as a shock during the GFC, and through below trend growth afterwards.

If the government didn’t expand public debt through deficit spending during this time, the outcome would have been even worse. The private sector’s decision to consume less than it produced and save during this period forced the government to expand the deficit to make up for this decision.

Leaving aside an external deficit or surplus, the government, no matter the party in control, will strive to run the opposite position to the private sector.

When the private sector is in deficit, consuming more than it produces, the government can run a budget surplus in a show of fiscal restraint while economic growth is good. This is a strategy that wins votes.

It wins even more votes if, in this instance, a government cuts taxes to minimise a budget surplus.

However, when the private sector is in surplus, consuming less that it produces, the government will run deficits2, helping the economy at an aggregate level, while targeting those groups that placed the government of the day in power. This also wins votes.

In essence, the private sector has already voted for the type of government economic policy it wants well before it gets to the polling booth through the economic decisions it makes.

By deciding to save the private sector determines the size of the budget deficit that will at least maintain unemployment (or any other metric it determines to be important) at a given level.

This newsletter (worth a read after this as it ties into this theme) also comes to the same conclusion and reiterates how the private sector chooses to have governments that support the policies that it wants – which also includes high asset prices and low volatility.

The private sector surplus must equal the public sector deficit if we want the status quo to remain. There is just no other way around it.

The dominance of public sector borrowing in the US has meant that the share of government debt of total debt has risen.

From a low in the 2000s of about 17%, the share of government debt has risen to 32%, returning us to post-war readjustment levels.

This relationship is true everywhere

Spain

Spain was an example brought up in last month's newsletter when talking about countries that had to adjust due to a refusal by foreigners to continue to fund a current account deficit. The external situation triggered the de-leveraging which hurt the private sector the most (as banks had been the biggest beneficiary of the capital inflow).

Strong private debt growth from the inception of the Euro (partially enabled by large capital inflows) allowed the Spanish government to de-lever over this period while still recording extremely strong nominal GDP growth of >8%.

The bust in the housing market, the primary destination for this private debt, forced an unwind. Over the next 10 years Spain experienced barely over 0% nominal GDP growth, as government debt rose by 60% of GDP to try and plug the hole.

European politics disallowed Spain from expanding government debt any further, but private sector de-leveraging hasn’t really finished yet, explaining Spain’s poor result of <5% nominal GDP growth over the last 10 years.

Private sector debt is now below the early 2000s as a percentage of GDP and shows little sign of stopping its de-leveraging momentum, making Spain look like a country desperate for a currency devaluation.

Greece

Sticking with European crisis countries, Greece turned out to be a more extreme version of Spain.

What made the Greek episode so difficult was that the public sector had borrowed an incredible amount even before the private sector started de-leveraging.

With no ability by the government to buffer the huge private sector surplus, nominal GDP growth averaged negative 5% over the subsequent 9 years.

I spoke earlier about how an economy adjusts when both public and private sectors must run a surplus. This is it, and it is painful.

Germany

Germany, Europe’s saver (not saviour), partially funded the excess both in Spain and Greece through its persistent current account surplus.

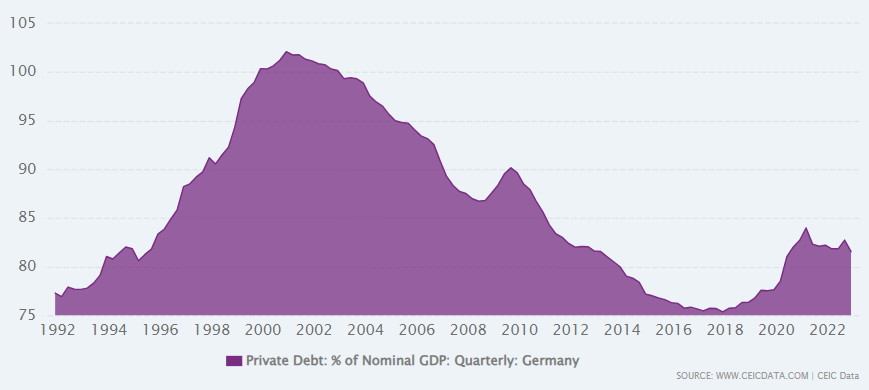

Being the model of self-discipline (and mostly helped by that current account surplus), the German private sector de-levered after the inception of the Euro, reducing private debt just as countries like Spain and Greece increased theirs.

The mirror image should be expected, as the large external imbalance for both countries would guarantee to be manifested in debt levels for each.

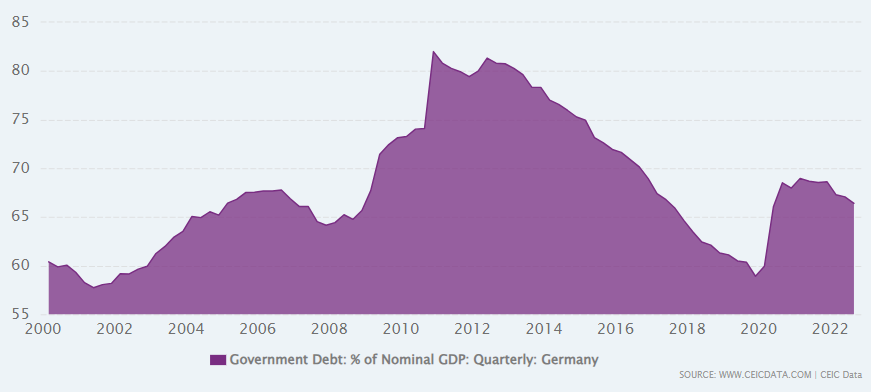

Germany’s private sector de-levered at the same rate both before and after the GFC. Over this period the public sector added debt, and then also de-levered from the start of the Euro crisis (2011) onwards.

Even when government debt did increase before the GFC, it was at a very slow pace, only increasing by 10% of GDP.

These dynamics ensured poor nominal GDP growth throughout the entire period. With well-known demographics issues and low potential growth, Germany produced only 2.5% nominal GDP growth before the GFC, which improved only after private sector debt slowed its contraction in 2014.

After the de-leveraging stopped, nominal growth surpassed any period since the mid-90s, as Germany consistently grew at above 3.5% in nominal terms as the private sector surplus narrowed. Calls for Germany to deploy capacity in both the public and private sectors to drive EU growth is a suggestion that would work.

Canada

Canada has expanded private sector debt since the mid-90s, with a further acceleration in in the few years preceding the GFC. Over this period the government has de-levered, reducing debt by 30% of GDP (before the pandemic).

Nominal GDP growth in Canada has been relatively good compared to other developed countries but has slowed over the last decade despite a consistent private sector deficit.

This could be because of the efficacy of that debt – maybe it isn’t provided as much of a boost as before, especially if it is largely finding its way into the housing market.

Australia

Another country well known for its housing market, Australia.

Australia, unlike Canada, slowed its private sector deficit after the GFC, and as a result the government reversed from tax cuts and surpluses to tax hikes and deficits to maintain growth.

In a similar picture to the US, Australia offered a textbook example of how the private sector changing its preferences for consumption and investment and thus changing how much debt it accumulates engenders a response from government.

The growth (or efficacy) of the growth in government debt hasn’t been sufficient. Nominal GDP growth in Australia has slowed from a 6% pace pre-GFC to around 4-5% afterwards.

Not blaming politicians is liberating

It’s easy to be angry at politicians when it comes to large public sector deficits. Some break it down into a partisan issue, but the experience over the last 10 years would suggest that either side of the aisle just has varying degrees of the same largesse.

The reason for this consistent view on deficits is that all voters want economic prosperity and will vote out anyone that doesn’t use the tools available to them to achieve that goal. No US president has been re-elected while in a recession, and there is good reason for that.

Our society is not fully capitalist, as there is an expectation that government will, to some extent socialise some risk associated with the uncertainty of the future, especially when that uncertainty is higher than it would be otherwise.

Why is the private sector generally running a surplus?

While commentators focus on why the political class is running a certain budget balance, the better question to ask is why does the private sector have a preference to save and be in surplus, leaving the job of maintaining economic growth with the government?

Frankly, I don’t know the answer to this question, and it should be one that is attacked in a future newsletter. I can present some initial thoughts.

At the highest level, there could be an explanation lying in either the tolerance of risk has changed, or the outlook for future risk has changed.

The GFC could have reduced the opportunities available to risk-takers, or the very nature of past debt growth could have created opportunities that just wouldn’t have existed otherwise.

It could also be that asset prices are so high that they already incorporate a future where risk and thus volatility are as low as it was previously – making any investment that involves rising risks in the future untenable.

There could be other factors, be them regulatory, social, or psychological. Did extreme losses form the GFC change the psyche of the private sector sufficiently to force it to run a surplus?

Large fiscal deficits are a combination of want and need

The private sector, as citizens, wants to maintain their quality of life. This means maintaining economic growth and asset prices in the range they have been in the past.

However, the private sector is unwilling to take on risk to enable this economic growth to occur. For whatever reason it has decided to save rather than spend, to take on a more austere existence and not take on debt to invest for returns in the future.

A contraction in private sector debt because of this surplus would result in below trend growth if the government were not to expand its deficit to fill the gap. In those countries where the public deficit wasn’t large enough, economic growth was well below prior levels.

This choice starts with the private sector, not with the public sector. The political class just do what they need to stay in power, and due to the want of the private sector to keep growth in a historical range, they spend.

Future private sector deficits may stop this trend, and even allow government to de-lever. This is not impossible and has happened in the recent past. However, something will need to change in the ability for the private sector to take risk for that to happen.

Right now, the private sector is slowing down its demand for debt once again, right as budget deficit growth is reaching a peak. This will spell the end of the post-pandemic economic miracle in time.

Whether the borrowers or the lenders decided is irrelevant.

Running budget deficits isn’t available to all countries of course and is the reason why emerging nations experience for more crisis that developed nations do. It requires a strong external standing and/or a current account surplus.

Man this is amazing. Who are you? Have you written a book?

Hey Peter, coming from another article of yours. Have two questions that might be easier than what I'm making them out to be but want to hear your thoughts:

1) Why is growth so dependent on increasing leverage (both public and private)? Is it because productivity gains have slowed?

2) If both the private and public sector decide to save/borrow (assuming govts don't want to smooth out the cycle), is that inevitably countered by a current account deficit/surplus?