Cross-border capital flows have shaped the world

There are a few truly macro trends that, if they change, the world must change around them. The direction of cross-border capital flows is one of these.

Balance of payments data rarely moves markets on release. The level of the trade balance for countries like China matter somewhat to markets, but pale in significance to timely data about the business cycle.

However, in the long-term, the balance of payments (or more specifically the current account) is one of the most important pieces of data that and shapes economies, and thus the relative performance of markets.

Countries have taken an almost permanent role as importers or exporters, and these rankings have been permanent since roughly the 1980s, itself a result of US offshoring which started all the way back in the 60s.

It wasn’t Bretton Woods that caused this. In fact, the end of the gold backing was merely just adjusting to the new reality of a globalised trade driven economy, where cross-border capital flows became more significant.

Economies and markets have structured themselves around these flows, so much so that it is impossible to change, lest we risk sovereign defaults and global conflict.

The balance of payments

Some basic economic principles first.

The balance of payments describes the flow of trade and investment payments against its identity, capital and investment flows.

The current account for most countries is made up of the trade balance (describing the import and export of goods) and income related to investments, such as dividends and interest payments. It also includes transfer payments which might be foreign aid or remittances.

Since we don’t trade with Mars (yet), the sum of all current accounts of all countries should add to zero1, so a large current account surplus must be offset by the same aggregate of deficits.

In other words, a large exporter must have importers to trade with them, who are equal in size. This obviously makes common sense.

The current and capital account reflect two sides of a ledger, in the same way set of accounts would be constructed for a company (or a household).

If a country runs a current account deficit, it is consuming more than it outputs and thus must have capital coming in to pay for this over consumption from the rest of the world. This happens through asset sales, or an increase in debt.

A surplus country is experiencing the opposite, increasing savings (capital) that will be exported.

Countries adapt to these capital flows by manufacturing financial assets or debt for foreigners to park their capital. This investment, in large enough size, shapes the economies of both countries.

Persistent deficits (and surpluses) shouldn’t exist

The last 40 years is defined by the persistent role that countries have played as either current account surplus countries (in which they export capital) or deficit countries (where they import capital).

In a perfect world, however, this dynamic should not exist.

A global economy with unfettered trade between countries with freely floating currencies and mostly mobile industries would react to balance the imbalance. If one country found itself in a less competitive position than another, the currency of the importing country would depreciate as currency is sold to buy goods form the exporting country.

Imports would become more expensive, slowing demand. If this is persistent enough, that industry may move across to take advantage of the weaker currency, balancing trade between the two countries.

The world, especially for the major superpowers, is far from being this simple. There is a litany of reasons that imbalances may persist, including:

Fixed or managed exchange rates;

Trade policy (which can include subsidies or import duties);

Natural advantage (resources); or

Diplomatic policy

For 2022, the world’s trade can be summarised by reducing to only the important countries:

Each group roughly equals $1.2trn or about 50% of all cross-border flow, all within the handful of countries above.

While these numbers are for 2022, these relationships have remained static for a long period of time, with the US becoming a deficit country after it started to offshore industries to a rebuilding Europe in the 1960s.

The US is the lynchpin, acting as the world’s consumer. The US lost its position as a surplus country in the late 60s, when the US started supplying Dollars to the world, allowing offshore borrowing and economic diplomacy.

How a country finances a current account deficit

The other side of the ledger is the capital account. This describes the flows of capital cross-border to finance a deficit, or where wealth accumulated from a surplus is invested.

Falling back to our earlier comparison, a company or household can finance net outgoings by either selling assets or raising debt. A country has the same options, and the mix that is achieved is going to be a result of the preferences (and opportunities available in each).

Most sovereigns and their markets can create assets (whether they be debt or equity) that foreigners can invest their money into. These are considered liabilities for the deficit country, just as issuing equity or debt is a liability for a company.

The amount of assets that become a liability for the deficit country must increase if that country is running a current account deficit.

The most common way a country finances a deficit is by increasing debt.

This debt can increase at any level of the economy, whether it be household, corporate or government. Where this occurs is simultaneously a function of the lender and the borrower (in terms of the assets available to be burdened by that debt).

This implies that it is not just the choice of the citizens becoming more indebted to take on that debt; it can be a result of the external situation which they may have little control over.

This country may be in a poor trading situation with others, a victim of disadvantage in competitiveness for virtually any reason.

Selling assets to finance a deficit is rarer than just using debt. Selling the crown jewels to fund a deficit isn’t particularly politically palatable; it only happens in situations where there is a severe power imbalance.

To avoid the deficit in the first instance, citizens could reduce their standard of living to bring a current account back into balance, but this option frequently pales in comparison to taking the capital being offered from foreigners that are hungry to sell stuff to them.

To be clear, the causality here is unclear as well. There is an argument that the current account causes the debt, or that a desire to borrow and consume (or invest) drives the current account. It works in both directions, settling at a status quo that an economy is comfortable with.

Sometimes this dynamic goes very badly.

The Eurozone, as an example

One of the best examples of cross-border capital flow causing an irresponsible accumulation of debt was Spain in the lead up to the GFC.

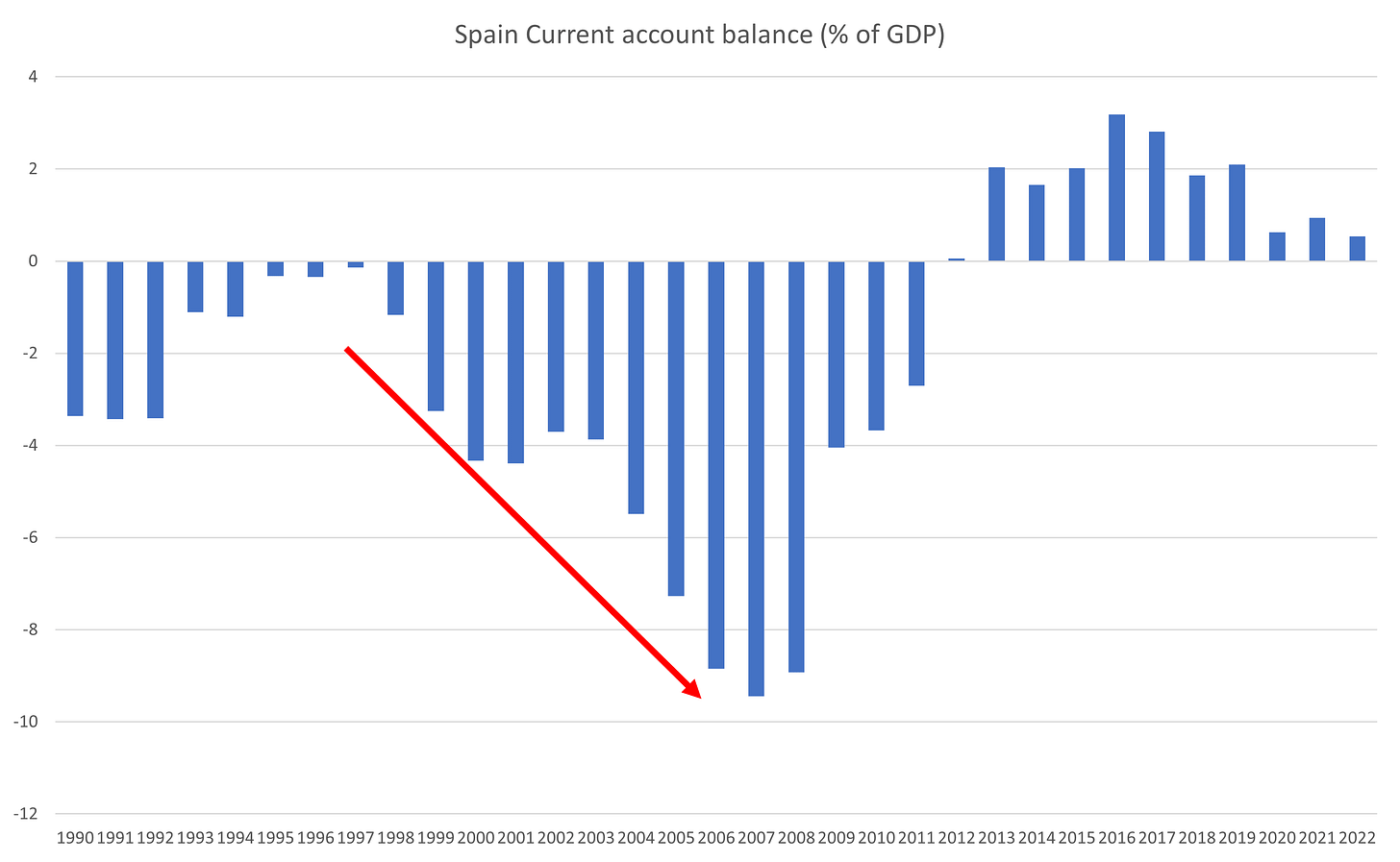

From the introduction of the Euro, Spain’s current account moved from being balanced to a deficit of 10% of GDP within 10 years. Prior to being within the fixed currency regime, Spain ran a current account deficit of 0 to 2% of GDP, well below GDP growth.

Spain (along with other Eurozone countries that suffered both in the GFC and the sovereign debt crisis a few years later) struggled to compete under the fixed exchange rate mechanism inherent with membership of the EZ.

This deficit (was mostly a result of the trade balance) was happily financed by surplus countries in the EZ.

Where did the debt accumulate? It wasn’t at the government level, with Spanish government debt to GDP falling over this period from 62% to 35%.

Where the debt accumulated was at the household level, through the banking system. This funded mortgages that fuelled the worst GFC housing crisis outside of the US and Ireland. It also led to the private financing of an incredible amount of infrastructure, some never to be used.

Spaniards attempted to maintain their quality of life with debt while their competitiveness worsened on joining the Euro. Since there was no exchange rate to adjust for this, debt accumulated and was deployed on unproductive ventures.

Spain rectified the problem by taking that standard of living hit in the years after the GFC. Imports stayed static while exports grew, effectively curtailing their consumption (and standard of living) to bring the system into balance. The journey back to an external surplus was painful.

To lessen the blow of this private sector surplus, the government borrowed to support demand. Government debt to GDP rose from 38% pre-GFC to 100% of GDP in 2016, when the external balance got to surplus.

This is not the first time Spain was allured by external capital. Many attribute the downfall of Spain as an empire because of the influx of gold from the Americas.

Spain is not the only power that has been a victim of large capital flows. War reparations throughout the late 19th century and early 20th had negative effects on both the losers and the winners.

It is impossible to discuss these effects in the modern world without talking about the US. Here, the effect of the current account, itself a pre-requisite for being in the ownership of the world’s reserve currency, drove the GFC, the shale revolution and the tech boom.

The US – a rotation from credit to equity

Net International Investment Position (NIIP) accounting highlights how preferences have shifted for how foreigners choose to allocate their capital in the US.

NIIP accounting shows the accumulation of the capital account over time in investments, split into assets (foreign assets owned by US citizens) and liabilities (US assets owned by foreigners). The method of accounting is through a quarterly market valuation, meaning that asset price movements affect NIIP accounting values as well, so caution must be taken.

There are 3 main categories: portfolio investment, direct investment, and “other” investment.

Portfolio investment measures valuation of assets held with minority ownership, while direct measures controlling stakes in debt and equity. “Other” mostly covers investment in banks and the financial products they issue.

In a similar theme to Spain, the US current account deficit grew rapidly in the 2000s.

There was also a large rise in capital available for housing, with most of this capital coming in through bank related financial instruments (money market, wholesale debt and securitisations).

As a proportion of GDP, other investment rose rapidly during this period (in assets that generally don’t change from par value). Portfolio investment increased modestly, while direct investment was flat.

The rise in other investment matches the increase in the deficit, strongly pointing to evidence of a similar trend what we saw in Spain – foreign capital flows had a lot to say for what went wrong in US housing over that period.

Things shifted considerably after the crisis, as “other” investment fell, and direct became the preferred destination for capital. This could include direct assets such as housing or land, as well as controlling stakes in public and private companies.

In the second instance it likely is maintaining valuations given the flow of capital. It could also be thought of as encouraging the exponential growth of “revenue-free” tech companies. Indeed, Masa-San is just one figure that represents this cross-border flow of capital (who was investing on behalf of the Saudis, another strong surplus country).

Portfolio investment continued its rise as well. US Treasuries are included within this segment.

While it’s difficult to ascertain the exact amount that is making its way into US stock markets every day, it remains a preference for foreigners. This has a powerful effect on maintaining the “buy the dip” philosophy and explains the S&P500’s constant outperformance over other regions.

Despite emerging from the greatest downturn since the Great Depression which inflicted demand contraction for years to come, the US equity market outperformed nearly every other region over the subsequent 10 years.

Outperformance against the Australian equity index is one of my favourites. Despite Australian nominal GDP growth outperforming the US over this period and a resource heavy index going through one of the largest resource booms in the history of the planet, the US still outperformed, reversing pre-GFC underperformance.

Over this period the size of the listed stock market in the US achieved new highs in relation to GDP.

A pivot for capital inflows into stocks over credit as a result of the housing crisis is a significant factor for the outperformance of the S&P500, and will continue to be. The US has the deepest markets precisely because it has to; everyone is invested as a consequence of being a importer of capital.

Surplus countries can get into trouble too

The cross-border flows detailed here are useful to explain trends at the asset class level. While balance of payments data isn’t timely enough to use this as an indicator for short-term trading, it is useful for overall trends and the likelihood of “irrational exuberance” continuing to exist in those sectors.

I’ve illustrated how the status of the current account dictates how debt can be accumulated, and some examples of where this debt has caused severe market impact. This can be a big problem for the creditor as well as the borrower, especially if that country decides to accumulate debt internally as a result of its own policy.

Earlier we attributed the rise in the US deficit to be from the rise in the surplus of China, Germany and Japan over the last 40 years. We’ve considered the US, but what has happened on the other side of the trade?

Germany has managed to avoid significant private or public debt, deriving its growth from the external sector instead. That story is different for China and Japan.

Debt has been the engine of growth in China, in the form of bank and quasi-government lending.

Since the bust of Japanese industrial dominance in the late 80s, a private sector surplus (through corporate and household deleveraging) meant that government debt had to grow to step in for that surplus. And grow it did. Government debt to GDP grew from 70% to 260% of GDP over 30 years.

This mirrors our prior examples of Spain and the US of government debt filling in the hole left by demand generated from private sector borrowing.

With such a large overhang of debt, why has Japan managed to stay crisis free for the last 20 years, while the run-up for Spain and the US lasted mere years before they were caught out?

A surplus must stay a surplus when there is debt

Highly indebted current account surplus countries have no option but to maintain their surplus, or risk crisis.

If Japan fell into a large external deficit, they would be as susceptible to crisis, like one that inflicts a small emerging market country. This wouldn’t be immediate, but if a deficit needed to be funded with outside capital it opens a vulnerability that can no longer be solved by politicians or a central bank.

A situation like this for small EM countries can be worse because of a reliance on borrowing in US Dollars. Japan likely wouldn’t have this issue as it might be able to borrow in Yen, but a sudden stop in this funding would have to be made up for by an equally fast contraction in economic activity to rectify the external deficit.

For Spain (and the US), the government stepped in to make up for that fall in private sector activity. That option would not exist for Japan until it had adjusted to be firmly back in surplus for an extended period as a result of high existing debt.

Fortunately, Japan has a buffer of foreign “savings” that it has accumulated by running a current account surplus for such a long period of time. This is reflected in Japan’s NIIP, which is significant in size. Like a household, a large savings position can get allow you to consume past your means for a while, but ultimately Japan (or China) would have to regain their surplus positions again to stave off potential default.

China, long reliant on investment over consumption, will find it impossible to rebalance towards consumption as the engine of economic growth for fear it might cause imports to rise, and tip the current account into deficit. A requirement for a surplus hampers economic evolution.

Of course, if these countries must be current account surplus countries, there must also be deficit countries on the other side. The US is fit for this role because it gains benefit from an international currency supported by demand by nearly everyone, and a perception of risk-free government debt.

The role that surplus and deficit countries play is the status quo that must survive for the current global economic model to continue without interruption.

Perhaps one of the 3 surplus countries, either Germany, Japan or China, may be able to switch to being a deficit country. In fact, if Germany completed this move, then the Eurozone would become far more stable than it currently is.

China and Japan might be beyond this point. Japan may be able to convince foreign investors of its investment grade status to fund a deficit for a while; but China would have a much harder job of this considering the way foreign bond investors have been treated in recent years.

A severe change to how the current system of trade balances work would eventually threaten the very stability we have relied on.

Superpower governments cannot default; war will come well before that.

Persistent surplus or deficits are both bad

Countries who are exporters and run a current account surplus tend to be considered as “virtuous”, in which their country essentially saves by consuming less than they collectively output.

The problem is that in a world where every buyer of your goods needs to be financed, the decision to save just means you invest in the countries that are buying from you. You may be saving just to put your money into a country that can’t pay you back because you hollowed them out and made them create worthless asset classes for you to invest into.

Japan and China show that the “savers” don’t necessarily avoid the problems of their trading partners. Debt can still accumulate internally, even if it doesn’t externally.

Even though all of this isn’t immediately tradeable, these trends are extremely important for 3 reasons:

They help explain why some markets tend to outperform others;

They explain how and why bubbles form; and

They help us understand the incentives for how different countries act.

The last point should be the most important take-away here. Understanding the limitation imposed by the necessity of a current account surplus helps to understand why China and Japan make the choices that they do; and what choices they will make in the future.

In reality the calculation of these statistics on a country-by-country basis introduces significant divergences

Hi Peter. Excellent post. I have followed Michael Pettis' work for a while as well. You mentioned the ASX and as an Australian I have watched the ASX basically go nowhere for 15 years. However, as you would be aware our property market is very bubbly and I think much of it is explained by Michael's work and your post. Most people I talk to still seek the answer elsewhere - immigration, planning laws etc. I would be interested to know your thoughts as I can clearly make a link between the surplus countries and Australia's property bubble. Thanks Steve

“Perhaps one of the 3 surplus countries, either Germany, Japan or China, may be able to switch to being a deficit country. “ - why did you word it that way? Why not switch to balanced country? Or does balance simply not exist, and all we can hope for is less imbalance?

Do you have recommended reading list on this topic?