Low interest rates don’t drive up asset prices – governments do

Despite the appeal of the hypothesis that lower interest rates encourages the private sector to take on debt, the data doesn’t support it. So why are asset prices so high?

Macro-economic data shows that debt accumulation by the private sector has little to do with the level of interest rates. This suggests that it is not low rates that are the dominant driver of asset prices, but the success of continual economic intervention by governments and central banks instead.

Both high inflation and deflation are unstable and uncertain states for an economy. Intervening to steer the economy a more stable, low inflation state is far more beneficial to asset prices than the outright level of interest rates. It’s low inflation, and not low rates, that drive asset prices. The “greed is good” decade of the ‘80s shows this.

Therefore, hiking interest rates to defeat inflation is paradoxically based in the hope that our economy will return to its prior “Goldilocks” state of low inflation. This course of action will not help to reduce asset prices or leverage, even if interest rates go up in the interim.

Our desire for these interventions could suggest that the central banker’s role is merely a manifestation of our desire to avoid any financial consequences of our own.

Heated conversations about central bank policy are common these days, with views on policy eliciting the type of response you’d get if you were talking about religion or politics.

Those deeply dissatisfied with the recent bout of heavy inflation tend to point their finger at central bankers for running too-easy policy for too long a period. It’s hard to critique this, as nearly every bank has run policy at the easy end of the spectrum for decades now, usually measured by models that they have themselves created.

When you ask those most vocal about the evils of central bankers what they would do differently, the answer is always to tighten policy significantly to get away from easy money and eradicate inflation. This, at least, is consistent with their view. Engaging in the conversation any further will ultimately find themselves faced with a conundrum. What happens when your policy tightening, effective or not, starts to result in real people losing jobs? Do you keep on tightening even if inflation is still persistent? At which point does the pain of inflation look pleasant next to mass unemployment?

Most people with empathy would suggest that central banks should once again ease policy, for the pain of unemployment surely is at least as bad as inflation was not long ago. This puts us right back into easy policy, the source of anger for so many.

It is this cycle of intervention that removes uncertainty from our economy, whether it be uncertainty of inflation, or uncertainty of unemployment. The government, and not central banks, drive this cycle of intervention, and they do so because we consistently vote for it.

It is this certainty, and not low interest rates, that drives high asset prices. Lifting interest rates aggressively during high inflation is ultimately based, paradoxically, in the hope that our economy will return to its prior “Goldilocks” state of low inflation, an environment that brought us high debt and asset prices in the first place. The stability of the economy is far more important than the level of interest rates for risk taking, and risk taking is what drives asset prices higher.

Our desire for these interventions could suggest that the central banker’s role is merely a manifestation of our desire to avoid any consequences of our own personal fiscal actions. To explore this, we need to consider the interaction between monetary policy, debt, inflation, growth, and the political reality which binds it all together.

Do low rates encourage debt?

The first question to answer is whether the level of interest rates influences how much debt the economy is willing to accumulate. Almost everyone agrees (even the central banks themselves) that the weight of debt on the global economy is of foremost concern.

The too-easy policy issue arises initially in the process of the economy going into recession. Central banks will generally lower interest rates to ease policy and improve financial conditions in the economy to stop any negative-feedback loops occurring. Lowering rates helps to bolster consumption, encourage investment at the margin, and restrict the amount of destruction in the economy so it can get back on its feet faster.

Once the economy does get back on its feet, however, monetary policy has never (in the last 40 years anyway) returned to its previous level of restrictiveness. A simple chart of the Fed Funds rate confirms this, and it this trend is held constant over most developed market economies.

Surely with all this evidence, the popular opinion is the correct one. If only those central bankers tightened policy more, then the massive debt accumulation wouldn’t have happened, and the economy would be healthier and more balanced? Not if you consider the actors that decide to accumulate debt and analyse their behaviour. Not to say that the central banker hasn’t played their part; but they attract an outsized amount of vitriol.

It seems intuitive that lower interest rates would encourage more debt. Dig a little deeper and it isn’t clear that just having cheaper debt will cause the economy to take on more debt, indeed if uncertainty about the future is high then the impulse will be to pay down debt (even though it’s cheaper) rather than to take more on.

Analysing corporate debt-to-GDP in the US confirms this effect. Corporate leverage falls in recessions. Companies de-lever through a recession and tend to only re-lever much later in the cycle.

This implies that the easing of monetary policy during recessions isn’t enough to encourage corporates to amass debt. It’s only well after the recovery that corporate debt as a proportion of GDP rises.

Similarly, we can’t see justification for this in household borrowing either. Household borrowing rose before and after the high in rates in 1980. During the easiest policy in a lifetime after the GFC, household borrowings decreased as the excess from the housing boom was unwound.

This leaves household borrowing only slightly higher than was it was in 2000.

In fact, if we leave out the ‘80s, debt-to-GDP across household and corporate borrowing has only increased by about 27% of GDP, a very small amount considering rates have fallen from 8% to zero.

The financial sector shows a similar trend to the household sector. Deregulation brought a large size increase to financial balance sheets in the late ‘90s, but a lot of this has reversed in the ultra-low interest rate period after the GFC as regulation was reinstated somewhat and risk taking was unwound.

The story changes when you consider the government’s role as a (very large) actor in the economy. Government debt rises in recessions due to the help it provides to the economy. Strikingly, government debt has also continued to rise after recessions in the last 40 years, indicating that the government will take on debt no matter what stage of the economic cycle, or the level of interest rates.

Since 1980, federal government debt has risen by 90% of GDP, dwarfing households, financials, and corporates.

These results seem counterintuitive and really put a dent into the idea that lower interest rates encourage debt growth, especially when we look at average nominal and real interest rates that prevailed during each period.

The 1980s had the highest average nominal and real rates. A real rate of nearly 5% is well above real GDP growth during the period, so this should have been tight policy for the time. Yet this was the period in which most of the growth in household and corporate debt occurred for these two categories, with the government adding a considerable amount as well.

Further, more debt was added by interest-rate sensitive parts of the economy during the era of highest nominal and real rates than in the 30 years after it (with the slight exception of the financial sector).

If we assume that the government is not an interest-rate sensitive borrower (which it shouldn’t be, given that it should adjust spending by need rather than opportunity), then the idea that low rates encourage debt growth is unlikely to be true.

To extend this, it also means that low interest rates aren’t sufficient to drive asset prices. But we know for certain that asset prices have escalated rapidly. What else could it possibly be? To answer the question, we are going to have to go back to first principles of asset pricing.

Asset Pricing 101

A student of finance is taught this early in their course when learning about different asset pricing techniques such as the discounted cash flow (DCF) model. In each of these models, lowering interest rates lifts asset prices.

Responsible usage of these asset pricing models will also include a discount for the uncertainty of the cashflows. If future cashflows are highly uncertain, then using a bigger discount rate is prudent.

It is generally the case that the discount for risk is far more impactful to a valuation than the discount for interest rates. In other words, perceived downside risk (or lack of it) is more powerful in driving prices than lower interest rates.

Most assets benefit from increasing certainty of their outcome (otherwise known as falling volatility). This makes good sense, as you would likely pay more for something that had a high certainty of delivering what you expected. This is the reason why companies like regulated utilities trade at far higher earnings multiples than a general corporate, for example.

The uncertainty component of a discounted cash flow model is the explanation for why asset prices and corporate leverage fall in recessions. Uncertainty and volatility rise far more than interest rates fall, and as such encourage an unwind of debt.

If interest rates were all that mattered, a recession would see asset prices rise and hence debt grow. But this only happens after uncertainty has subsided.

The Volcker, or the egg?

Governments, supported by central banks, have helped to crush the discount for uncertainty by acting swiftly to disallow the economy from operating in an unstable state.

High inflation and deflation are unstable states for an economy. High inflation can possibly (but not necessarily) lead to even higher inflation states if a feedback loop takes effect. Deflation has a similar effect just in reverse, with the added kicker being that deflation in a high debt environment can lead to a severe debt crisis. It’s for this reason I argued in a prior newsletter that deflation is far more of a risk than high inflation is in the current debt-laden environment.

When Paul Volcker attempted to tame inflation with aggressive interest rate hikes in the ‘70s, he set the precedent that if the economy were to find itself in an unstable state, the Fed would do what is necessary to fix it. Whether it was the rate hikes that brought inflation under control isn’t really the point.

What was important was that economic volatility of the ‘70s, present in the form of inflation, recession, and weak equity markets, were no longer tolerated by the Fed. Average economic growth was strong during the ‘70s, and debt loads fell. However, the economic volatility and lack of certainty was far more politically problematic.

The Fed Chair prior to Volcker did not see things this way. They correctly identified that the source of inflation was from government spending and saw the high inflation (or high uncertainty) as an intentional side effect of large fiscal stimulus. Who is the Fed to go against the will of the government, which is supposed to be representative of the people? This is a fair question to ask. Should the Fed try to undo what the government has seemingly done on purpose?

This is where the problem becomes one of the chicken, or the egg. Was the culprit the Fed, who decided to eliminate high inflation by targeting inflation and thus volatility, or was it the government, in creating this economically uncertain environment and the forcing the Fed to fix it?

The Goldilocks zone

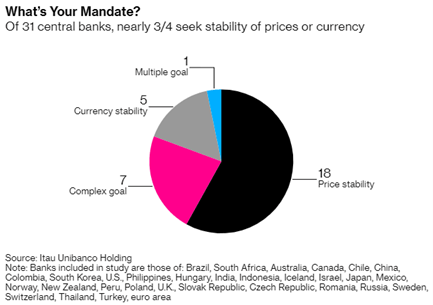

The instruction to suppress volatility is codified within each central bank’s official inflation mandate. This mandate, in an official sense, was first adopted by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 1992, and it pioneered the idea that a central bank should primarily be responsible for price stability over any other aim.

Price stability for developed economies is mostly defined as an inflation rate of around 2%. This value is sufficiently far enough from the unstable deflation state and any situation that could be deemed a high inflation state.

An inflation rate of 2% has historically delivered an environment that isn’t too hot or too cold, but is just right. For this reason, we will refer to this 2% target as the “Goldilocks zone”.

Inflation targets are generally imposed on central banks through act of government. By placing these mandates on a central bank, the central bank is trapped between running easy policy as a result of the drag from the accumulation of government debt, and running tight policy if excessive government spending causes inflation.

Inflation mandates makes the central bank look like an arsonist, and but in reality it makes them more of a firefighter against the fire that is fiscal stimulus and the debt that comes along with it.

Your vote is a vote for Keynes

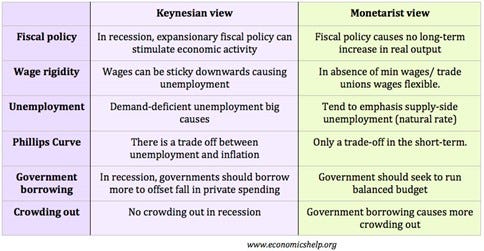

There are very few things that politicians on both sides of the political aisle will agree about, except for one thing - the deployment of fiscal stimulus during a recession.

No matter if the politician is a liberal or a conservative, they subscribe to Keynesian economics and its view on government intervention in downturns. In most countries with a two-party system, both sides have not only conducted some sort of fiscal expansion in a recession, but this amount has tended to grow with each subsequent cycle.

Of course, the reason for the unanimity on this topic is because it is also hugely popular with voters. While there are consternations about fiscal deficits and the national debt at other points in the cycle, when unemployment is rising and asset prices are falling, most are thankful for any sort of government intervention.

Increasing the size of government by increasing the amount of spending is also in a politicians best interest, as a bigger government increases their power as a cohort.

Like the Fed’s intervention when inflation is too high or too low, the intervention by the government through deficit expansion serves to dampen the amplitude of the business cycle, which is analogous to suppressing the natural volatility of the economy.

The cost of stability

A healthy economic system requires volatility, and the destruction it brings. The most potent form of destruction is debt defaults, as they “clean the decks” and allow asset prices to reset.

However, if too much of an economy falls into default, it can lead to a reduction in trust in the banking system. A fragile banking system makes healthy destruction into something much more catastrophic, as even well priced assets and performing debt gets caught up in the vicious unwinding of leverage.

Because of the fragility this structure introduces, there is a certain amount of insurance that the government and the lender of last resort (central banks) must provide to stop a spiral becoming total collapse. Knowing where this line resides is difficult. The cost of providing this stability to the banking system is not the amount of capital or lending these entities must provide, as it almost always gets this back, with interest.

The real cost occurs by misjudging the point at which assistance is provided, and how much is needed. If too much is given to the banking system to save it, then the government has essentially underwritten some assets or businesses which should not have survived, and which go on to act as a drag on the economy in the future. There is no doubt that it is very difficult to know where this line is, but the effect over time, if subtle, is still very real.

The cost of stability has more recently become ongoing, and less care has been taken to overstep the line. Nothing shows this better than the increase in government debt after the GFC. Even with record low interest rates, the uncertainty introduced by the housing crisis caused households to re-evaluate and paydown debt.

From the GFC until around 2015, the government continued to add debt to offset the de-leveraging of the household sector. If the government had chosen not to do this, consumption would have fallen and potentially put the economy back into recession.

Thus, to maintain certainty and to eliminate volatility, the government was forced to take on more liabilities to fund a return to the previous economic regime, as a de-leveraging economy was unable to support it on its own. The “cost” of this was high asset prices that never adjusted, and an inefficient economy that needed ongoing support.

It is important to note here that those countries that didn’t experience an unwinding of household debt also didn’t experience a housing price crash like the US did. Australia and Canada fall into this category. As household debt didn’t unwind, the government was not required to borrow. As a result, government debt in these countries remains relatively low, and increasing household debt maintains consumption instead.

For most other developed economies, however, the government funded economic activity by aggressively borrowing to ensure that the low volatility regime of the 2000’s was persistent, even after the shock of the GFC.

This increase in government debt had to be matched with easy policy from central banks to offset the deflationary effect of that debt. Eventually too much spending caused inflation, and central banks are now lifting rates to offset.

Central banks have had no option, lest they were to act against their inflation mandates. Once again, the central bank is the firefighter, and not the arsonist.

Imagining a different world

If the central banker is the firefighter, it challenges the argument of those who are angry at the prior choices they have made. On the one hand they are correct - constant accommodation in disinflationary environments have helped to entrench low volatility markets.

Where they are wrong is it’s not the low interest rates in themselves that have caused high asset prices. It’s the low volatility environment engineered by the government’s promise to do whatever is required. Low rates and high inflation would hurt asset prices. Low rates and deflation would hurt asset prices. It’s the unstable economic state which hurts asset prices, not the level of interest rates.

This equally applies when hiking rates in an inflationary episode. When recalling Volcker, a central bank critic should remember that he may have ended the volatility of the ‘70s, but he also implicitly gave the “OK” for the excess and leverage of the ‘80s.

In addition government, and not the Fed, were largely responsible for starting the fire the Volcker had to put out, and then demanded he fix it. The techniques used to fix this situation are still used today, and asset prices continue to be affected by it.

Asset prices are just a function of certainty about the future. A certain future is one with predictable growth and predictable inflation. A strong certainty about the future is enabled via the eternal promise that those in charge will do what they need to avoid any sort of environment where certainty is sacrificed. Governments and central banks have doubled-down on their commitment to zero volatility, and therefore asset price growth has accelerated.

If you need convincing of this, think about which outcome would bring more volatile markets over the next few years:

Aggressively tightening policy now with the goal to bring inflation back down into the “Goldilocks zone”, coupled with the promise to ease again if necessary; or

Having the Fed come out and set rates at 5% and pledge never to shift rates again, no matter what inflation or unemployment does.

I can guarantee that the second option would bring the end of the old world and cause a repricing of everything. Economic risk would finally have to be assessed properly, and this would be reflected in asset prices. The first option, while it seems aggressive, is still another attempt to act as God and bring markets back to an environment they love most. It may cause some pain in the short-term, but long-term nothing would change.

So, if you truly want a world in which asset prices come down to reality, debt is reduced, and speculation is at a minimum, you are going to have to vote for leadership that will not react when inflation is high, unemployment is high, growth is negative, the banks are in trouble, or deflation is an issue. I don’t know many people that want this (which includes myself). For this reason, the environment that we find ourselves in now is purely of our own making, representing our desire to avoid any financial reckoning. Financial reckoning is a requirement to fix mistakes of the past.

Having the Fed hike rates aggressively to break inflation right now is not the answer. In fact, it is just another reinforcement of the policy that created the world as it exists. The only way for asset prices and debt to come down is to say goodbye to the protection of our leaders, and let the economy sort out everything on its own. Doing this, however, will not be pretty.

Maintaining high inflation will work to reduce debt loads BUT if they persist for long enough then interest rates will just adjust and make it more difficult to reduce debt after the initial break from expectations.

Wow, fascinating, this explains so many developments around the world.

I guess a way to keep the system of government debt stabilizing the economy working would be a higher (but stable) level of inflation, to inflate away debt? Which would be in line with the current inflationary geopolitical trends?