On the brink of fatal policy error

Tempting deflation by aggressively tightening policy before we know if inflation is embedded is irresponsible. The cost of deflation is greater than inflation, and could be impossible to fix

Despite inflation printing at 30 year highs, deflation is by far the greatest risk to the global economy over the next 5 years, just like it has been for the last 10.

Comparisons to the ‘70s are incorrect. The Great Inflation began in the ‘60s and took 5 years to take hold, leaving central banks today with plenty of time to assess the situation.

The world’s central banks have unanimously decided that this risk, the stated reason for countless rate cuts and massive bond buying programs since the GFC, is no longer of concern.

By casting away this real risk and acting too early on what could possibly be a short burst of inflation, central banks escalate the risk of deflation while still having insufficient tools to deal with this scenario if it arrives sooner than anyone thinks.

Inflation is as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man. – Ronald Reagan

He was right. Inflation is painful, it hurts the least well off the most and it increases inequality as corporates benefit more due to pricing power. However, when he said this he thankfully didn’t have to consider the absolute hell that is deflation in a highly indebted economy.

Right now consensus is that central banks need to act fast to ward off this apparent inflationary disaster that is upon us. Comparisons to the Great Inflation of the ‘70s are everywhere. It doesn’t help that inflation has become a political topic in the US either; this severely limits the US Federal Reserve in its assessment of the matter.

These fears are misguided, are plagued by short-term thinking, and to be frank, a desire to overuse the tools at our disposal to do something all the time.

The real issue at hand is still deflation. The debt load which was taking us towards a deflationary trap is still with us and larger as a result of recent fiscal stimulus. If the Fed panics and hikes too aggressively to prevent inflation which isn’t endemic, then the window to deflation will be opened again and it will happen so fast that no amount of easing will prevent it.

This is where the real risk appears. If the Fed is wrong, then it is never going to have enough ammunition to get us out of deflation after it happens.

On the other hand, if the Fed holds off hiking too aggressively and inflation is found to be endemic, then it has unlimited tightening capability at its disposal to end it.

These risks aren’t symmetric because the tools we have to correct an inflationary episode are unbounded relative to the tools we have to end a deflationary episode. This means that the determination of whether we are indeed in a ‘Volcker moment’ (where rates must be hiked aggressively to end endemic inflation) is of vital importance.

The Great Inflation: The prelude to the ‘Volcker moment’

January’s US inflation print stood at 7.5% for the year. This is as high as it has been since the US was recovering from the Great Inflation of the 1970s.

Economists still disagree greatly on what caused the Great Inflation, which incidentally reveals the uselessness of economics as a science. Triggering events commonly cited include:

Abandoning the gold standard and moving to a free-floating currency;

Nixon applying price controls for 90 days;

Nixon applying import tariffs; and

The end of sufficient US supplies of oil, which caused OPEC to quadruple oil export prices until the peak in 1980.

Obviously these are a complex set of events, each with differing effects on an infinitely complex economic system.

The abandonment of the gold standard is often cited by gold bugs as the reason for the inflation of the ‘70s. There is some truth to this. Abandoning the gold standard caused a depreciation in the US Dollar of roughly 30-35% over the decade, with a reversal occurring only after inflation peaked in 1980.

A depreciation in your currency is inflationary, as imported goods paid for in a foreign currency cost more.

It is inconvenient to the narrative then that the effect of a depreciating currency, in addition to the import tariffs and oil price spikes, all happened after 1971. In reality, however, inflation was already biting by the end of the ‘60s, making the cited reasons for the Great Inflation merely events that exacerbated a problem that was already well embedded. Yearly urban consumer inflation hit 5.8% by the end of 1969 after being extraordinarily low and stable in the decades after WW2.

The primary cause of this was Lyndon Johnson’s administration embarking upon serious fiscal stimulus from 1965. Persistently large budget deficits that funded ambitious social programs including the ‘Great Society’ initiative which was to reduce poverty to zero, and equalise home ownership across races. This period also brought the Food Stamp program, Medicare and Medicaid.

The spending associated with this was significant, as detailed in this article:

LBJ's increased government spending added $42 billion, or 13%, to the national debt. It was almost double the amount added by JFK, but less than a third of the debt added by President Nixon. Since Johnson, every president has increased the debt by at least 30%.

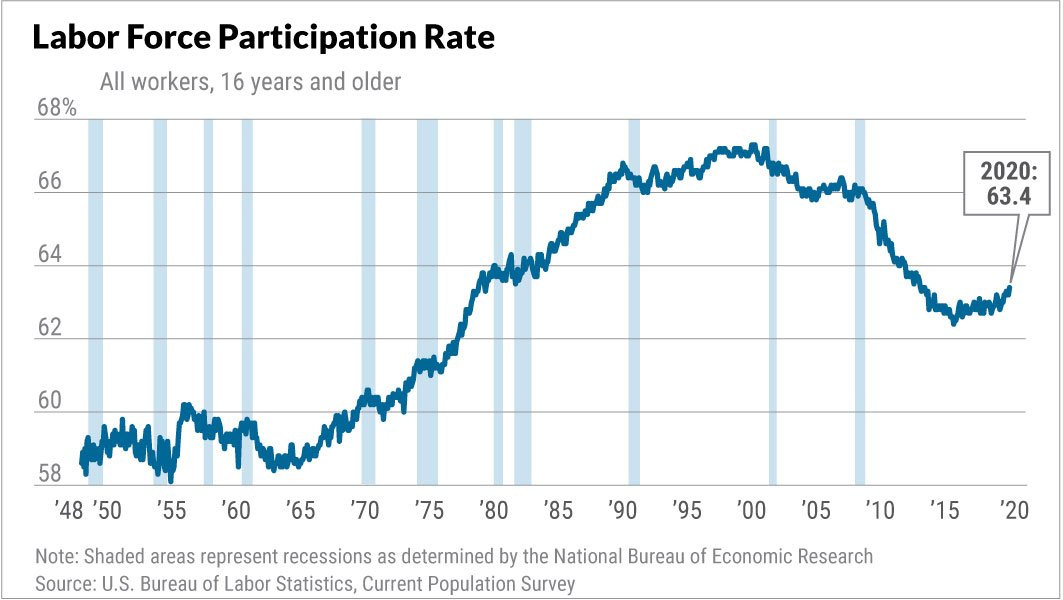

Another much ignored trend at the time was the incredible labour force growth as a result of the women’s movement. The participation by married and single women in the workforce started growing in the mid ‘60s, which propelled the participation rate from a steady 59% to 64% by 1980. Since wages continued to grow despite the extra supply of labour, the demand effect on the economy was strong.

The effect on this can be seen through average GDP growth rates for each decade. Despite all the headwinds for the US in the ‘70s, she still achieved a growth rate only a little less than would be expected given the secular downtrend in growth since the War.

The next part of the equation was the was the Fed’s reaction. Inflation started slowly and then accelerated from 1966 onwards. It is important to note that despite oil supply concerns at this time, oil prices were falling into the ‘70s and as such were not a factor.

The Fed was aware of nascent inflation problems but decided not to react, preferring to aim at the source of the inflation:

In the 1960s, years of cajoling by Martin’s Fed to persuade President Lyndon Johnson’s administration to restrain the budget deficit failed to pay off. Despite constant soul-searching at Fed meetings on the danger of price rises taking hold in the buoyant American economy, the Fed underestimated the persistence of inflationary pressures.

With the benefit of hindsight, Martin’s Fed not acting to quell inflation was particularly egregious given that it didn’t arise from external and uncontrollable factors such as rises in oil prices or (ahem) serious supply chain issues.

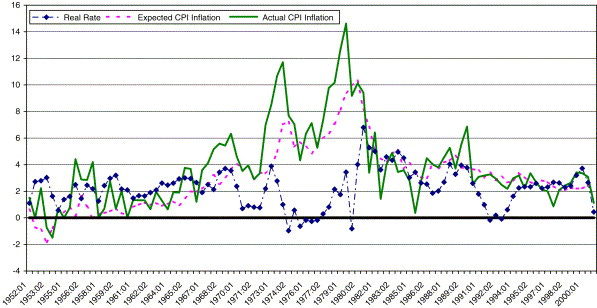

By not reacting to this slow and steady uptick in inflation, the Fed allowed the public’s expectation of inflation to rise as wages followed. It took 4 years for this to become embedded, and a slow hiking path for the Fed Funds rate in 1969 was, at that point, not enough to stop it. A recession starting in December 1969 wasn’t enough to put a real dent in inflation either, which prompted Nixon’s price controls.

Inflation became embedded and was persistently high because of a strong upward trend in inflation expectations.

Inflation is more about psychology than economics

Expectations of high inflation causes workers to demand greater wage settlements, and gives confidence to companies who are hesitant to apply price rises to goods. This creates an upward spiral of prices, with price rises causing wage rises which in turn begets more price rises, and so on.

Game theory can explain these outcomes. While the best outcome for everyone would be to cool the spiral, for any individual actor in the game the personal best outcome is to demand a price rise as the environment allows them to make this demand, and this leaves everyone worse off in the end.

In the 70s, Nixon hoped to break this game by installing price controls as part of the departure from the gold standard in August 1971. It’s unbelievable that he considered this to be a good idea. While I can understand the argument that this could break the cycle by slowing decision making down, once the window of price controls is over, you will have accumulated delayed price hikes due to lagging input price rises which would just kick the cycle off again, only this time more viciously.

The next significant factor contributing to situation in the 70s was the Arab state embargo. Oil prices tripled and at that point the Fed had no chance to stop what was happening without some drastic action.

Volcker didn’t have a choice

Caught in this spiral, Fed Chair Arthur Burns was too busy considering philosophy:

In a lecture at the annual IMF meeting in Belgrade, Burns reflected that Fed credit tightening to counter ‘upwards pressure on prices released or reinforced by governmental action’ tended to cause ‘severe difficulties’ for the economy. Stepping hard on the brakes, he philosophised, meant that the Fed ‘would be frustrating the will of the Congress, to which it was responsible [for] assuring that jobs and incomes were maintained, particularly in the short run’.

Of course, he’s right. This is very relevant for the situation we find ourselves in today given the fiscal stimulus of the last 2 years. The key difference is that this is only in the context of an economy without a serious inflation expectation problem. A terrible wage price spiral caused by elevated inflation expectations will cause ‘severe difficulties’ on its own, making the decision to hike rates a ‘free of consequence’ choice in the context of there being very little to lose by doing it.

Paul Volcker on his appointment to Fed Chair in 1979 recognised this issue and did what Burns was unwilling to do. By doubling interest rates (and being helped greatly by falling oil prices) he managed to break the back of spiralling inflation expectations and set the US economy on an entirely new course in the ‘80s.

Volcker didn’t have much a choice, but the great benefit was that the choice available to him would have very little consequences if it was wrong. This is the key to knowing whether 2022 is really a ‘Volcker moment’ or not. Is hiking aggressively risk-free, or is there a chance it will lead to a worse environment?

The forgotten risk: deflation

In March 2015 the ECB began its Quantitative Easing program that lasted 4 years and resulted in €2.7trn of bond buying. In the minutes of the February ECB meeting they described their reasoning for starting QE:

“Against this background, the risk of second-round effects had increased further and, with it, the risk of too prolonged a period of too low inflation,” they said. “This, in turn, raised the possibility of deflationary forces setting in, which would not permit an attitude of ‘benign neglect.’”

The chart below highlights what effect these actions had. In respect to Eurozone core inflation it was able to maintain inflation from sliding any closer to zero, but was ineffective at raising inflation. Without knowing what would’ve happened in the absence of bond buying, we cannot say if deflation was to be a reality, even with the benefit of hindsight.

The ECB were justified in panicking about the threat of deflation. An environment that is simultaneously debt laden and has falling prices will quick devolve into a crisis, as revenues and wages will struggle to cover interest payments on previously accumulated debt. Interest payments definitely do not fall in sympathy with prices therefore deflation creates a debt crisis very quickly.

Effectively, deflation causes the stock of debt to balloon in value versus the nominal size of an economy.

This is called a ‘deflationary trap’ and is difficult to get out of. If monetary policy is at the lower bound, it is impossible to get out of.

Deflation is far worse than inflation

An inflationary environment has the opposite effect when considering previously accumulated debt. In outright Dollar terms, rising wages and revenues can more easily cover interest payments. This is referred to as ‘inflating away debt’. Obviously living costs also increase, but after a few years of more brisk inflation, the previous debt load will be smaller in comparison with nominal GDP. Misery will increase in severe bouts of inflation, but for an indebted economy it is still preferable to deflation as long as inflation stays within the realms of sensibleness.

This takes us back to Volcker’s actions. To bust the ever rising inflationary spiral in the late ‘70s, Volcker raised rates viciously, and these rate rises forced everyone to re-think how they approached their own role in the spiral. Break the economy and you’ll end the behavioural aspect of increasing inflation expectations.

The hiking couldn’t be measured, or gradual, or data dependent. It had to be swift, decisive and brutal.

It is handy then that there is no limit to how much interest rates can be lifted to ‘break’ an economy. No upper limit exists so if growth and inflation continue to go higher, just hike another 1%. And then another.

Shifting behaviour when deflation is in motion is no different. A determined central banker will have to ease policy so quickly and provide so much stimulus that the chain of reducing prices stops and then broader economic restructuring can help to fix the issues that caused the deflation in the first place.

Unlike the case of tightening monetary policy however, there is a clear limit to how much policy can be eased given where rates and other stimulus are right now. Even if the Fed hikes as much as the market prices, there is not enough dry powder to prevent deflation if it becomes a risk in the near future, as we’ve seen from the ECB’s experience between 2015 and 2018.

Given this risk, tightening policy now has to be done very carefully, lest you leave yourself in a disastrous situation and little dry powder to deal with a possible deflationary scenario in 2 years’ time.

We’ve had a stroke of luck – don’t waste it

The ECB and the Fed have been worried about deflation since the GFC. The volume of fiscal stimulus and monetary support in 2020/21 may not have been instigated to finally break the deflationary trend, but it ended up having that effect. We’ve wished for inflation for 10 years and happened upon it due to the unpredicted consequences of policy decisions made in response to COVID.

The ECB has been praying for 2% core inflation and now all of a sudden they have it, so why do they want to get rid of it? Embedding expectations at this level is what they’ve spoken about doing since QE started so they need inflation to settle at this level to achieve that.

Nobody knows what’s going to happen to inflation in the future. Therefore when deciding what the right path is for monetary policy there are two things are of the utmost importance:

1. Don’t tempt deflation again by tightening aggressively in an attempt to try and break an inflationary cycle that may or may not be there;

2. Respect the fact that we have very little ammunition to break out of a deflationary trap if hiking aggressively ends up being the wrong thing to do.

There is plenty of time to evaluate the landscape, and, like Volcker in the ‘70s, if things do get out of hand there is so much optionality to the upside of monetary policy to destroy inflationary expectations if they happen to arise. When considering what could be done if deflation were to re-emerge, the opposite is definitely not true.

Therefore, the responsible thing to do is wait given the asymmetry of risks and outcomes. The ‘Volcker moment’ was unique in that there was little downside risk to trying to break the inflationary spiral at that time. Today, being so close to deflation and being burdened with so much debt changes the odds of success of a similar course of action.

As a result the risk of policy error is higher than it ever has been in the past. There is a point at which the Fed hikes too hard where there isn’t enough easing capability to reverse the mistake. This is particularly important as the chance of policy mistake is high given the Fed’s insistence to ignore the fact that tapering is policy tightening, along with jawboning a bunch of rate hikes this year.

If central banks hike like the market prices then be aware of the spectre of deflation in the very near term. It’s a risk we shouldn’t have ever forgotten about.