Low unemployment is a European mirage

The lowest unemployment rate ever means little for Europe’s struggle to stay out of recession

Mario Draghi’s report on European competitiveness won’t contain anything of substance for those who are students of the European economy. It could have been written 10 years ago, with the only meaningful changes being the lamenting over Europe’s lack of leadership in 3D printing rather than AI, like the report suggests.

Self-reflection, however, is always welcome. It was the widening cracks in the industrial base of Europe prompted Mr Draghi’s report, a short 6 years after they started.

German industrial production has been the driver of the current Eurozone wide stagnation, with production nearly 20% off 2017 highs. The malaise began when China started to properly compete with Germany’s auto sector, the number 1 destination for R&D spending in Europe. This was followed up by the Ukraine invasion by Russia in early 2022, spiking the price of gas which is vital to several German industrial sectors.

These issues have been discussed to death and have affected the economic data already. While Mr Draghi’s report is has come nearly 6 years after the trend started and does have some worthwhile points within it, the ultimate answer to the problems is the same that he suggested with every problem he faced when he was the president of the ECB.

The answer was and is ‘more European integration’. The idea is that if you pool resources in a similar way to the “United States of America” and align incentives then Europe would be in a better position to compete on the world stage. “Euro Tragedy” by Ashoka Mody is an excellent journey through how the EU was formed and how the problems that existed right at its inception carry through to today.

Instead, this newsletter will concentrate on is the puzzle on how most metrics can be worse than during the Euro Crisis in the early 2010s, yet other indicators are better than they’ve ever been.

The most puzzling indicator is that despite the avalanche of poor economic data, the EU has the lowest unemployment rate since 2008.

This trend isn’t unique in the western world. The strength in employment post-pandemic, driven by strength in corporate profits, is only starting to show signs of weakness now. The common theme here is weakness in “white collar” industries where the hiring in and after the pandemic was the strongest.

With the US as the sole exception, growth has simultaneously struggled in low unemployment developed countries when you’d expect household spending from full employment to be driving growth. The most common explanation is inflation and high interest rates, but the US has had this too.

The glacial pace of labour market weakening (if it’s happening at all) is slowing the pace of rate cuts in many jurisdictions, despite their positive effects missing from GDP growth.

Europe is on the brink of recession

European growth has exhibited the same trends in growth for a long time. The mix has generally been low household consumption and fixed asset investment supported by external demand. Foreign demand for European goods has, due to a persistent current account surplus, also added over time.

These same trends help Europe emerge from the early 2010s Euro Crisis.

A strong external balance drove investment and allowed Europe to run at a lower level of domestic consumption (~1%) in the post-GFC era while (mostly) achieving 2% real GDP growth. The ECB was running zero rates and QE heavily over this time due to nominal, rather than real, growth being too low (i.e. deflation was a real risk).

Contribution from government was low – the region did just emerge from a sovereign bond crisis after all. This wasn’t a GDP growth mix you would complain about, given what the EU had just emerged from and the demographic backdrop.

Large European countries like Germany, Spain and France contributed to this outcome in a similar manner, increasing its robustness. Italy, however, struggled more during this period under austerity (Spain’s low government debt load helped it avoid the worst of the Euro crisis).

Contrast this with the current situation. The current growth picture is reminiscent of one just before a recession. Household consumption is basically zero, government spending is increasing. Spain is the only country holding growth up, but consumption is slowing there too. Germany is the worst of the lot, with growth that is zero. Trade is a drag for Germany, reflecting issues in its industrial base.

The growth picture presented is also before the pressures come down on France and Italy to reduce their deficits which are currently breaching enforced levels. Expect the contribution from government to come down as well.

There is little positive news to glean here. The question is how has this happened when employment is so strong? Why isn’t consumption running at an acceptable rate when gainful employment is more common than ever?

“Make-work”

There is a distinction between economically valuable work that increases economic activity and work that isn’t economically valuable and doesn’t increase economic activity. Whether work is one or the other has nothing to do with the amount that the job pays and is usually only observable ex-post.

Consider the classic example of paying a man to dig and hole and then fill it up again. An allegory for government stimulus in recessions, it comes about from making up a job that is so utterly useless that it is clear that it adds no economic value, and its only purpose is to provide an excuse to pay that man so he can consume it on goods which causes production of those goods which does contribute to GDP. This is also known as “make-work”.

It is not the work that has added any value to the economy, it is the debt that was increased that paid for his consumption. The “work” was just an excuse to increase debt and spend that money in the form of stimulus.

Of course, it’s better if the work itself can also add to economic value by fulfilling a need that was previously unmet.

The same problem can affect other forms of stimulus. Modern stimulus has been to spend to expand infrastructure, but if this infrastructure doesn’t increase overall efficiency and create economic value, then it is as good as digging a hole and filling it up again.

The opposite is valuable but unpaid work, such as domestic work. This is work that needs to be done and adds to GDP even if its unpaid (although it is not directly measured, it will be visible in greater production elsewhere if it is genuinely value add).

We can aggregate out these effects by just dividing total output by the number of employees. The link between the employment and effect on GDP can be tracked by measuring the output per employee per hour, or labour productivity.

The chart above shows this measure for the Euro area. Here this measure has broken from its post-crisis trendline and has been tracking sideways since the pandemic.

Labour productivity is a key factor in real GDP growth, along with capital and total factor productivity (TFP) growth.

Without a boost from productivity, real GDP growth is reliant on population growth or a deepening of the capital stock, both things that Europe also struggles with. Labour productivity growth is working against the increase in total employment to keep baseline European GDP growth pinned close to zero.

The nominal economy got larger, but this hasn’t translated to the real economy. With little potential GDP growth, it won’t take much to tip Europe into recession, despite the ultra-low unemployment rate.

Everyone loves a government job

This same trend is affecting most developed countries. The drivers across these economies are similar and are mostly directly related to the pandemic.

I want to preface this by saying that it has not all been a bad news story. Private sector employment has grown impressively with the jump in corporate profits that occurred after the pandemic. While profits didn’t all flow into higher wages, it did flow into an increase in total wages paid into the economy, and thus an inflation of the nominal economy.

Professional services the world over saw strong hiring after the pandemic, and while those markets have slowed their hiring (especially in tech), mass layoffs haven’t yet begun.

You may think the proliferation of corporate work-from-home employment was what hurt labour productivity, but this isn’t entirely the case.

For Europe, the stagnation of labour productivity is due to a mixture of two different drivers:

Employment growth being weighted towards the public sector; and

A reduction in hours worked per employee across the board.

‘Hours worked’ is important (and may be affected by work habits changing) but it is the public sector that has more to answer for. The chart below compares the growth in gross value add from each sector and employment growth since before the pandemic.

While the public sector accounted for 40% of the increase in employment from end-2019 to end-2023, it only accounted for half of that in gross value add.

In other words, allocating more human capital towards public sector employment has caused average output per employee to decrease. The private sector has continued to grow productivity in-line with previous growth rates. It is the sharp growth in the public sector that has slowed productivity growth.

Adding to these woes are a slowdown in hours worked, which fell by roughly an hour per quarter. The biggest falls in hours worked came in sectors that had increased employment the most (the average public sector employee in the EU works 2 minutes less per day than before the pandemic).

Employment in Europe is basically a case of great headline numbers with a horrible composition, and it’s this horrible composition that has seen employment not convert into higher baseline real GDP growth, causing core Europe to flirt with recession for a year.

Europe isn’t alone. Canada has also seen a large uptick in public sector employment and a fall in labour productivity.

Australia has also seen the same trend occur. Problems with public sector productivity are hurt by the increased weighting towards healthcare.

The UK has seen the same productivity issues as Australia, with the public sector similarly providing no productivity growth since the turn of the century. Private sector productivity growth slowed post-GFC partly due to the issues with the UK’s over-sized financial sector.

The US, however, is the exception. While recent headline non-farm payroll growth has been dominated by government employment, recently, as a percentage of total employment, government employment is still below pre-pandemic levels. Employment fell by 800,000 during the pandemic as schools were closed and teacher were laid-off. This deficit has only recently been made up which leads to this suprising result despite the recent growth in in government hiring.

Low unemployment in the US in general hasn’t been enabled by public sector hiring, and this has kept productivity growth, and US real growth, higher than their peers.

Admittedly the US is running a fiscal deficit greater than its peers, something that I’ve covered multiple times and have attributed it to a huge driver of the low volatility and outright dominance of US growth over other western regions.

The almost certain bull case for US growth

My last newsletter drew out the linkages between domestic debt accumulation and GDP growth. It’s time to put those conclusions to the test.

The form that this stimulus takes is more direct to the private sector, rather than using the roundabout method of hiring more government employees. This difference has delivered some impressive outperformance.

From mid-2022 the Euro area has recorded average real GDP growth of just 0.6% versus 2.9% in the US. On a per capita basis Europe looks better because of slow population growth, but when you include a per capita measure across the countries in the chart above, high immigration countries like Australia and Canada look absolutely woeful.

There is no doubt labour productivity growth is important to overall growth outcomes and proof that full employment is no guarantee of good economic growth.

With Euro area growth where it is, and the manufacturing problems still trending against her, the probability that Europe falls over into recession is high.

When will the periphery join the core?

The term “PIIGS” ranks highly amongst the many terms that brings back PTSD for those that traded during the European sovereign crisis of 2011-2013. Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain led the recession, with some countries like Spain never really recovering at all from the 2008 financial crisis which arguably hit European banks harder than their US equivalents.

“Core” Europe did a lot better during this period, led by Germany. Germany’s behaviour (especially towards Greece) was enabled by their superior economic position which was always posed in a way that implied that the German propensity to save was the moral high ground. Of course, their saving is enabled by someone else’s spending.

The chart above depicts the components of German GDP smoothed over a 2-year period to better see the bigger trends in economic growth.

For the 2011 to 2013 period of the sovereign crisis German grew at a slow but positive rate. Business investment disappeared as you would expect, but household consumption remained positive at a rate in-line with usual German consumption and the usual reliance on exports remained.

Compare this to Spain. Spain didn’t have as bad a government balance sheet, but the echoes from the GFC remained well into the sovereign crisis as those liabilities ended up as the government’s problem.

Household consumption contracted for 5 years, as did investment. The external sector buffeted the deep recession, but this was mainly due to less import demand. The Spanish situation during this time was due to severe imbalances with the Eurozone.

The resolution of these internal imbalances over 10 years has left the situation very different today, so much so that the opposite is occurring. Spain and Ireland are the growth champions – so much so that people jokingly say that the Spanish Bonos are the new benchmark bond for Europe, displacing the German Bund.

It is now Germany who is the growth laggard. While not yet in obvious recession, it shows all the signs of being in one. Investment is contracting and household consumption is non-existent.

Normally Germany would be able to rely on external demand to be the saviour. Not this time.

If things go any worse, maybe the fabled fiscal capacity of the German Federal government will appear to stop Germany tipping over into recession….

…or maybe not.

At the European level headline growth is still held up, in large part, by the periphery. But even that looks like it might be coming to an end.

France is the focus for Brussels for now. Italy will the next on the block. Current proposals to reduce spending won’t be sufficient, so the classic European game of the periphery versus Brussels arguing about fiscal positioning will start again.

Now that the inflation impulse has disappeared and nominal growth deficiencies will return, we are back to where we were in the second half of the 2010s. Mario Draghi, writing reports instead of running the ECB, may be in the wrong place for such an outcome.

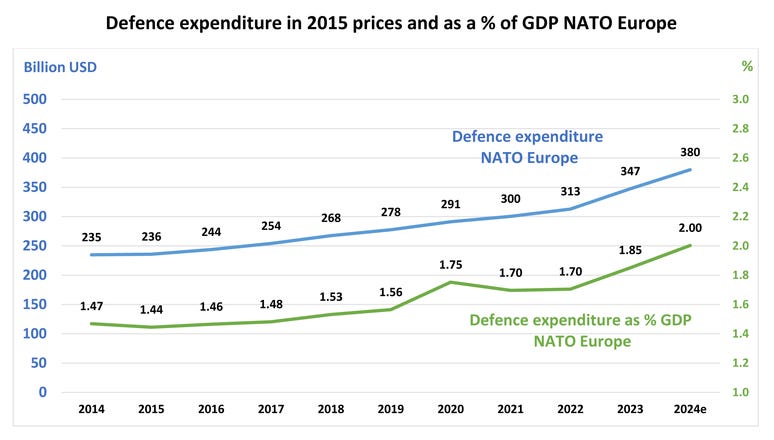

We can also now throw Donald Trump into the mix. Some European countries are bumping up against fiscal limits with the bare minimum of spending on defence.

France is one of the few countries that spends above 2% of GDP on defence in Europe. Germany lags after underinvesting for decades (there was one point in 2017-18 where their entire fleet of 6 submarines was inactive!). Italy spends only 1.5% of GDP on defence which just puts more pressure on budget constraints if it must be increased.

Countries like the US, the UK and France have home-grown defence industries so the spending can remain local (it also no coincidence that these countries tend to outspend those without a domestic industry). Most underspending countries don’t enjoy this luxury.

The plan for the ECB

The problem faced by the ECB will be different than that of the European crisis. The “fiscally irresponsible” countries just aren’t the centre of the problem now (even though Italy will always be the country that will be the trigger for an existential European crisis).

The problem is the engine that Europe has relied upon over the last 15 years is sputtering. Threatening tariffs on China for its encroachment on the auto sector looks inevitable, but it’s too little too late on that front. You’ll never get an apology from the Germans that mocked Trump for this stance, but it is telling that a moral opinion changes when it affects you directly.

Even if successful, they can’t stop China’s competitiveness in the export markets usually serviced by German autos. That effect will stand.

The change in the drivers is partly meaningless, as the outcome at the European level will look the same. Slowing inflationary pressures with stagnating real growth means horrendous nominal growth.

Poor nominal growth then brings sovereign debt loads back into focus.

The inflationary boom in many ways caused Europe’s economic metrics to appear better than they would of otherwise. Corporate profits increased, driving employment. Inflation drove nominal growth, making debt metrics look better.

This effect is over. The ECB is doing better than I thought they would at recognising this. Perhaps I’m too cynical after tracking the ECB over many years, but the fact that the slowdown originated in Germany may have made them get up and do something much faster than they would’ve otherwise.

I must admit I didn’t expect the cuts to happen as fast as they have mostly because of the fear of inflation and the historic slow to move nature of the ECB, rather than any other view of the economic trends, for these are obvious. Many have been burned by expecting the ECB to hold back to rate hikes because of the underlying growth dynamics.

Right now, there are still cuts priced in for this year. There is still the question of whether the ECB is willing to go back to zero rates. Will it need crisis again to get back to this point? Less of a question is the ECB’s willingness to buy debt if spreads move too wide. It’s hard to doubt that they will because once that door is opened it won’t be closed again.

The problems Europe faces are systemic and serious. It’s very easy to be negative on Europe and many have lost money playing into the trends that caused Mr Draghi to write his report. Don’t be fooled by low unemployment in Europe, it merely is a mirage.

Now that the ECB has started its cutting cycle the trade is much clearer. The easiest trade in the world in rates is to be positioned for continued rate cuts by the ECB.

Thank you, looked forward to this, a lot to think about.

Going back to easing policy, decoupeling from the Fed cuts makes sense. With high energy prices and decreasing outlooks for exports at least the lending market can be stabilized through artificially created inflation?

I think the fireing of the finance minister is a positive signal, as his agenda was anti-stimulus and maybe was one part of the puzzle which is holding back the EU from building up domestic consumption?

My bingo card, or hope, would be of energy prices coming down further, by an end of the ukrain war and/or lack of china or emerging markets energy demand? This would boost domestic consumption as, after the rising wages of recent years, income and savings get spent outside imported energy?

I would think that government work is, in general, less good for productivity than working for the private sector, only because these are lower-paid jobs, which therefore contribute less to GDP. And even if they are less productive for the subsequent economic sectors in the short term, they create social stability and quality-increases of the overall social infrastructure, which helps the economically advanced sectors in the long run?

Excellent analysis that exposes how superficial employment metrics mask deeper structural problems in the EU economy. Your focus on the productivity impact of expanding public sector employment is particularly insightful, but there's another critical dimension worth considering: the democratic implications.

The shift toward public sector employment represents not just an economic inefficiency, but a fundamental transformation in the relationship between citizens and the state. As more Europeans become directly dependent on government employment, national parliaments' ability to implement necessary reforms becomes increasingly constrained. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle where bureaucratic expansion further erodes both economic dynamism and democratic accountability.

Your comparison between German and Spanish economic trajectories illustrates this perfectly - it's not just about GDP numbers, but about the fundamental sustainability of the European economic model and its compatibility with meaningful national sovereignty.