In the throes of policy error

Too fast, too hard and without caution – After throwing everything and the kitchen sink at deflation, Central Banks are trying to compensate with serious consequences

Escalating rhetoric combined with rapidly accelerating action from central banks has resulted in sky-high bond volatility, declining liquidity and, more recently, forced liquidations.

Markets are on the back foot because rate hike expectations are continually uprooted, leaving the bond market with little basis for valuation.

Central banks are conducting an experiment on the global economy while changing the method of that experiment rapidly. This seems to have be done for no good reason other than what appears to be panic.

The uncertainty associated with this strategy is causing other problems which makes achieving their goal of “less inflation with recession” harder. This is what policy error looks like.

Generally, I’m not a fan of dunking on the central banker. Doing that usually means that other responsible parties, such as the government, get away with causing the discontent that so many express with asset markets and the economy.

This is not to say they are faultless either. I liken them to a bad trader, doubling down on momentum trades at the wrong time. Predicting the future is hard, and it’s clear they are no better than anyone else at it.

Right now, however, they are causing more problems than they are solving, and are directly and solely responsible for disorderly markets.

This newsletter is a follow-up to one of my most popular, entitled “on the brink of policy error”. In that newsletter I talk about the danger of an about face on the narrative central banks have been hammering on about since the GFC: the risk of deflation.

The trend has been for central bankers to come from academia. Academic central bankers are driven by economic theory, and the theory (at the time of the GFC) was that outright deflation was a death knell for an over indebted global economy. So, we got zero rates and as much Quantitative Easing (QE) as it took to avoid the outcome that was feared.

Then the pandemic supply-side shock along with a record government debt issuance and a confluence of other issues (mostly resulting from years of irresponsible energy policy) brought about heavy inflation, something that central bankers themselves had been praying for over the last decade, ironically.

As inflation worsened and became a key political issue, monetary policy tightening became progressively more urgent, and rate hikes moved from the traditional 0.25%, to 0.5% and then, suddenly, to 1% and beyond.

This represents a severe escalation and presents a problem for markets. This problem, entirely created by the violent swing in central bank behaviour, has recently resulted in issues that have now required more intervention.

By attacking the inflation problem in this manner, central bankers are effectively conducting a science experiment whilst changing the method of that experiment. This shows a lack of caution that may create other problems and unintended consequences which need even more intervention (sometimes contradictory).

This is what being in the throes of policy error looks like.

I understand high inflation is a sensitive issue, and I am not making any value judgements about the pace of inflation. Arguing for patience and caution from central bankers is more about avoiding the worst possible outcome through either destroying markets or putting the economy into a much bigger recession than might be necessary to slow inflation. This, in my mind, is what constitutes policy error, rather than the choice of any goal at the outset.

The requirement for further intervention is the reason for this follow-up newsletter. Below, I analyse the emergency action required by the Bank of England to put a ceiling on long-term UK bond yields and how this perfectly illustrates policy error.

The controversial Bank of England action

After a stunning rise in long-end UK bond yields, the Bank of England was forced to step in as a lender of last resort to buy up to £65bn of 30-year government bonds (Gilts) to stop yields spiralling higher.

In a little over a month, 30-year Gilt yields doubled from 2.5% to 5%, with the bulk of that move occurring in only a few trading sessions. It doesn’t take long when yields are moving in 0.5% clips!

The action came about due to the acute stress felt by UK pension funds as a result of these large moves. Pension funds are large users of interest rate derivatives which allow them to match the duration of their assets to their liabilities. The net effect results in a conversion of shorter term cash assets to 30-year assets, which revalue with the 30-year bond yield.

There is nothing inherently wrong with this, as this use case is exactly why derivatives exist in the first place. It would be a different story if the use of derivatives made these funds insolvent (where liabilities exceed assets), but this did not happen. In fact, the rise in yields resulted in outperformance of this type of strategy, a rare brag for anyone in 2022.

It wasn’t the use of these derivatives that caused this problem, but the requirement to “collateralise” the loss caused by such a violent market move.

Collateralisation reduces credit risk between counterparties. Forcing capital into escrow for the current loss on a derivative minimises the losses associated with the collapse of a counterparty. This all sounds prudent, on the surface.

However, the requirement to raise funds to post collateral creates another risk. In the case of a derivative user that has an opposing position to the derivative that doesn’t benefit from collateral coming in, posting collateral causes a liquidity risk rather than a solvency one.

The Bank of England action to backstop the 30-year part of the curve was due to this collateral situation affecting UK pension funds. The brutal speed of the sell-off meant that the pension funds couldn’t raise enough cash by selling other assets to keep up with the margin calls, despite not losing money as a whole.

These funds weren’t running too much risk, in fact they performed well given the dislocation in bond markets. Whilst UK pension funds were able to choose not to clear, market pricing for un-cleared derivatives essentially forced them this way regardless. This regulation was entirely a result of government action after the GFC, forcing nearly all entities to centrally clear their derivatives no matter how they used it, or with recognition of the actual risk that the user added to the system.

The construction of centralised clearing regulation is well covered by Craig Pirrong, otherwise known as the Streetwise Professor. His blog is well worth a follow. This specific blog covers the frequent hiccups of centralised clearing which is creating pro-cyclical risks in markets. The first paragraph covers the high-level well:

In the aftermath of the last crisis, I played the role of Clearing Cassandra, warning that in the next crisis, supersizing of derivatives clearing would create systemic risks not because clearinghouses would fail, but because of the consequences of what they would do to survive: hike initial margins and collect huge variation margin payments that would suck liquidity out of the system at the same time liquidity supply contracted. This, in turn, would lead to asset fire sales, that would distort asset prices which would lead to further knock-on effects.

His blog on the pension/LDI issue is here. Well worth a read.

Like the Fed’s $9 trillion balance sheet, broad regulation is creating unintended consequences that may introduce risk elsewhere, and the case of the UK pension funds is just another example of this.

The problem of one-way expectations

The Bank of England, like most central banks, regularly has its decision makers and economists give speeches to justify the Bank’s position and guide the market to its future moves.

The market takes these speeches extremely seriously, with not just the actual words having effect, but also the general tone.

The tone of these speeches by not only the Bank of England, but every other central bank, has recently been so hawkish and forceful that they broke equity and bond correlations that persisted for more than 20 years.

Examples of this type of absolutist speech can be found directly on the Bank of England website.

Catherine Mann, a member of the monetary policy committee (emphasis mine):

When thinking about the tightening undertaken to date, my concern is that the gradual pace of increase in Bank Rate has not tempered expectations enough, allowing the embedding of the short-term inflation overshoot into the persistent drift in medium-term expectations.

She then follows:

We cannot be complacent in the face of the short-term spikes and medium-term drift. Acting more forcefully now, to ensure that the drift does not become the norm, is designed to avoid depending on a deeper and longer contraction to return inflation to target.

There is little room here for any other interpretation than a single-minded goal which is to get inflation back to target. This tone has been repeated consistently by other members of the Bank, including the Governor, Andrew Bailey:

My best estimate is that inflationary pressures will necessitate a bigger response than we may have anticipated in August.

Each piece of aggressive communication just builds on the last, and like the UK 30-year yield, causes a compounding effect on expectations.

The Bank of England was just one of many

Strong messaging has been replicated by nearly every developed market central bank. It has ramped up slowly, coinciding with the panic associated with continued high inflation prints in nearly every jurisdiction.

The recent September meeting minutes for the Fed are just as clear:

The possibility that a persistent reduction in inflation could require a greater-than-assumed amount of tightening in financial conditions was viewed by the staff as a salient downside risk to their forecast for real activity.

This newsletter would be painfully long if I were to include all such examples.

Normally, forceful messaging can only go so far. The market will discount aggressive rhetoric, acknowledging that “jawboning” the market into a certain direction (in this case a higher terminal rate given their view on inflation) has value to the central bank.

However, in the last few months, a higher terminal rate (or the policy rate where the central bank has finished its hiking cycle) has been explained to be required to be able to bring inflation back to target. The market fulfilled this by increasing the pace of expected rate hikes per meeting and/or stretching out the length of the hiking cycle to match the rhetoric.

Simultaneously, the view on forward economic growth also improved during the August-September period, supercharging the sell-off in bond markets.

This manifested itself in higher terminal rates, less cuts after the terminal rate, and thus less inverted or steeper yield curves, depending on which market you look at.

From the low in yields in August until mid-September, expectations for rate hikes in the US by the end of 2022 increased by approximately 0.9%, and the US 10y Treasury bond increased in yield by 0.8%.

Despite the contortions in the yield curve during this time, the bulk of the move in US 10-year yields came from more immediate hiking expectations. This is generally the case, as the level of the 10-year bond yield is mostly explained by short-term rate expectations.

The moves in yield to mid-September were normal and reflected changing expectations. It was after this point where things became unhinged, which ultimately resulted in the Bank of England having to act as back-stop in a market that was quickly becoming disorderly.

It was by the second half of September that the aggressive rhetoric of the two months prior clashed head on with higher-than-expected inflation prints globally and, most importantly, accelerating action to back the rhetoric.

The chart above shows the cumulative total of interest rate hikes in each quarter since central banks started to unwind low rates after the pandemic. It is exponential in nature.

Humans that are trading markets are sensitive to this this sort of chart. In equity markets, prices following the same trajectory either up or down reduce liquidity and become self-feeding. Bond markets are no different.

An added problem was that the most important factor contributing to long-end bond yields, central banks, kept dislodging expectations by hiking even more than elevated expectations were ready for.

In one week, Sweden hiked by 100bp, Hungary hiked by 125bp. There was a bunch of above expectation inflation prints which didn’t help the situation, and then, finally to add insult to injury, a “mini-budget” out of the UK that was tone deaf to any of the trends currently happening in their own bond market.

Exponentially increasing expectations were being met with exponentially increasing action.

This last event was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. Panic escalated, and a relatively small market like the UK, stopped working properly. Selling created more selling, and yields were out of control. There is little explanation for yields moving higher by 50bp in one day, as expectations just don’t adjust that quickly. There was something seriously wrong.

What was wrong was that the market had lost all basis for valuation of yields. The market’s thinking is simple and rational: central banks have told us they’ll stop at nothing to slow inflation; they are acting on that with increased forcefulness; actual inflation is not slowing signs of slowing; and governments are making the job harder.

This rationale became circular until forced selling took over as the primary force driving expectations, rather than the other way around.

This illiquid and volatile market then took over as the determinant of UK policy, forcing a firing of the Chancellor and has put the Prime Minister’s job at risk, all because the Bank of England didn’t keep some control of its interest rate path, and instead let a malfunctioning market set policy.

How to temper expectations

The announcement to buy long-end Gilts introduced a bid for UK bonds that had disappeared as the market spiralled into disorderly operation. The reintroduction of a bid from the lender-of-last-resort encouraged others to bid as well and brought back an orderly two-way market.

But the fact remained, the Bank of England used emergency intervention in the market to offset out of control expectations of rate hikes caused by aggressive communication combined with an exponential acceleration in central bank action.

The hypocritical nature of their action is captured well by the tweet below:

Using emergency powers in this way to offset irresponsible expectations management is the worst possible way to use these powers.

It is illustrative of how panicking about inflation translates in unpredictable ways to a panic in markets. Control over the short-term rate path is the most effective tool a central bank has, and by losing control of the market’s interpretation of that path, it became impossible for the market to form an opinion on fair value with any level of certainty.

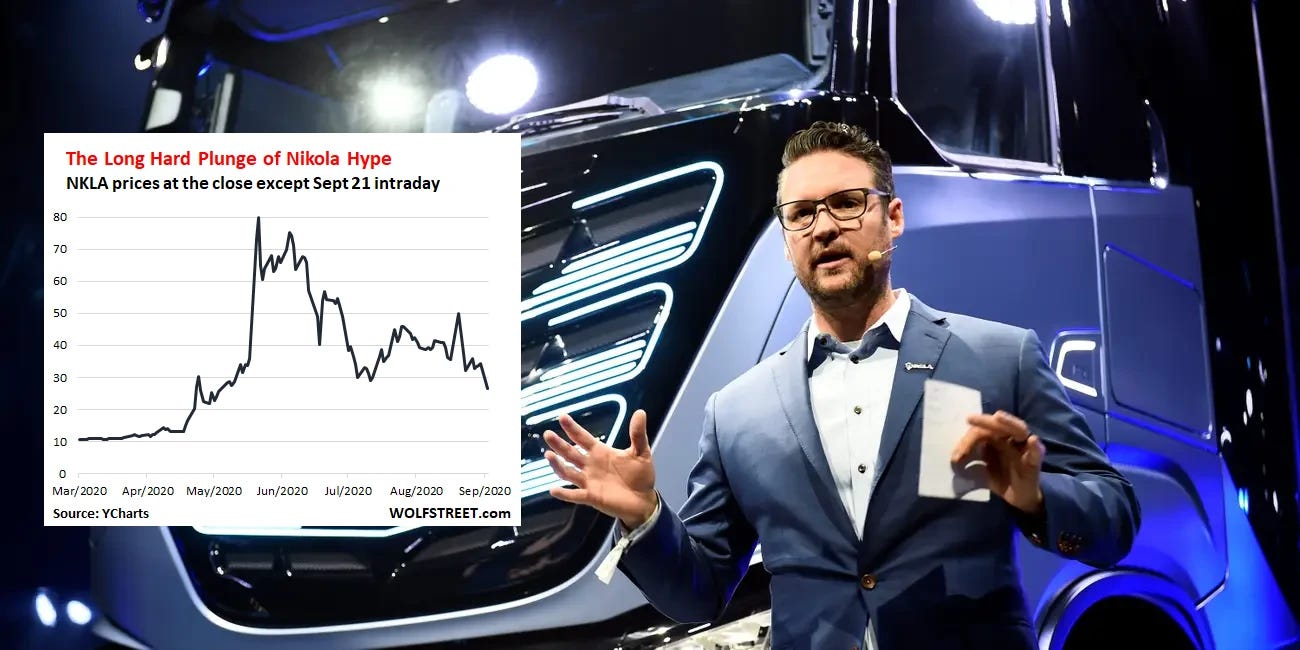

You wouldn’t be surprised when a company with exponential growth in earnings and guidance to more of the same had a stock price that traded exactly like the yield of the US 2-year Treasury bond this year.

Reality would have the final say on that company’s guidance, however. The market could still form an opinion on fair value based on the likelihood of achieving these forecasts. This makes the way that a central bank interacts with the bond market unique as it can manifest the outcomes that it guides to.

Imagine if a hype-master CEO could manifest their own exponential earnings path like a central bank governor could? How well would that market function? It wouldn’t at all. You could argue that crypto at the height of the mania traded like this.

The power of being able to deliver on any expectations you intentionally set must be used responsibly, lest you break the market like the long-end Gilt market did at the end of September.

Tempering expectations could have been done by simply putting a cap on the maximum interest rate hike per meeting. This would set a (still very high) ceiling on the 2-year rate, which would have brought the rest of the curve under control.

Predicting inflation and the effect of monetary policy changes is difficult and predicting it incorrectly is not an indication of policy error. The economy is an infinitely complex system, and to expect anyone to know the outcome of any one action, or to know the sum of the factors affecting that system is unreasonable.

However, policy errors occur when they creates adverse outcomes that bring more cost than benefit. This doesn’t mean creating a recession, as this is the explicit aim of hiking rates.

In my last piece on the topic, I argued that acting too hard on inflation too quickly could cause a situation where deflation is impossible to get out of. This would also be considered policy error.

But policy error can also manifest itself in execution. In what seems to be a panic about the lack of efficacy of previous rate hikes, or the stubborn way the economy isn’t falling into recession, the serious acceleration of rate hikes has caused far more problems to appear than are obvious from the supposed benefits of these changes to policy.

A science experiment with no method

Some may think that setting an upper limit on rate hikes reduces the flexibility to “fight inflation”, but 50bp per meeting over a year is still approximately 5% worth of hikes. If this isn’t enough, then the prospect of a disorderly bond market just can’t scare you. In fact it’s to be expected. It’s an inevitability of such a wide possible range of outcomes for the overnight rate.

When unbounded, the range of possible expectations that can be created when a 2% rate hike in one meeting is on the table is immense. In 6 months of meetings the policy rate could feasibly change by 10%.

This newsletter isn’t here to argue the basis of the need for such a high interest rate. I just don’t believe that a breakneck pace of rate hikes is a good idea because we just don’t know what is going to happen. The economy of today cannot be compared to the 1970s, and using that as an example is not responsible.

But like most things in economics, it is a belief. Economics is not a science as much as the academics that staff central banks today would like it to be. Since we haven’t got a tested hypothesis of what will happen if we raise rates this quickly today, what is happening now is a science experiment on the global economy where the null hypothesis being tested is “will aggressive rate hikes cause a recession, and will this recession subsequently end inflation?”.

It's akin to testing for a possible chemical reaction in science class except you don’t get the reaction you want fast enough, so you keep increasing the amount you pour into the beaker exponentially. Hope you’ve got your goggles on.

Nobody would run an experiment this way. The method would be laid out beforehand. Maybe you’d run different versions of the experiment with different “doses”. You surely would not change the method a short way into the experiment because it wasn’t going the way you wanted.

Central banks are conducting this experiment in such a way that they have already introduced other problems in addition to the one they are trying to solve. Their actions have decreased liquidity in markets, along with increasing volatility and hence uncertainty. Rates markets are trading at far higher levels than may ever be needed to achieve their goals.

The only explanation for the central banks’ decisions I can suggest is that they view inflation as accelerating. I just can’t see this in any developed market. Inflation continues to run at the rate it has been over 2022, it’s just that forecasting by analysts has recently been quite poor, with actual coming in far higher than predicted.

My immediate impression is that inflation and monetary policy have become so political that any semblance of caution just can’t exist. Financial stability is eroding and creating problems leading central banks to hypocritical and reactive policy positions.

Aggressively hiking still has the possibility of bringing back deflation far too quickly. Accelerating that aggression adds to the deflation risk, while mixing in a whole lot of financial stability risks as well.

Amateur hour. This, in my opinion, is the only way to describe how central bankers are conducting themselves right now.