The only thing QE did was destroy trust in the Fed

From its inception, Quantitative Easing has attracted an outsized amount of attention. Is this because it has a destabilising effect, or is it just because people don't trust something so complex?

There is little evidence that Quantitative Easing (QE) has the effect of lowering yields and flattening the yield curve. In fact, the evidence points to the opposite being true.

Examining what the yield curve does under bond buying periods reveals a contradiction – bond yields trade in the opposite direction to the Fed’s buying.

This makes it similar to all other types of monetary policy easing. More easing improves the outlook for the economy, which causes curve steepening.

Periods of QE are better for the equity market than when the Fed reduces its balance sheet. However, this is almost all due to a recovery in economic conditions rather than some QE driven bubble.

There is another explanatory variable. In each strong equity environment, QE was matched with large sized deficit expansion by the government.

QE’s complicated nature has destroyed trust in the Fed, outweighing any possible benefit it brought. This cost should’ve been considered at the outset.

An incredible amount of ink has been spilled on QE, and the supposed market warping effects of it. No other topic seems to generate as much emotion as the Federal Reserve’s version of extraordinary monetary policy.

Born in the unstable period after the GFC, QE was invented to allow the Fed to ease monetary policy past the zero lower bound for monetary policy (which the Swiss and European central banks managed to subsequently defeat).

Did QE manage to achieve this goal? Yes it did. There is no reason to believe that it didn’t ease monetary conditions, and the reaction of the bond market to QE confirms this.

Did QE encourage risk taking? At the margin, yes it did. QE works by taking interest rate risk out of the market. This is marginal however, and is worth only a few interest rate cuts, if that.

QE is frequently argued to cause yields on long-term bonds to decrease. But this isn’t the case. QE tends to lift yields, directly in opposition to the “portfolio rebalance theory”.

Let’s get into the truth about the effect of QE on markets, and whether it has been a big of a deal most say it has.

Examining the evidence

The hypothesis surrounding QE is that large scale asset purchases should keep rates lower through the constant intervention across the entire yield curve. Let’s test if this theory became reality. How do we do this?

It may be tempting just to look at outright bond yields to see what happened while the Fed was buying and when it wasn’t. This chart is presented below.

The outcome isn’t convincing at all. In some periods where QE was in force, like 2010, bond yields rose spectacularly, while they fell in others. At best, this presents a mixed picture for what happens during QE, and doesn’t prove whether yields are affected at all. Not a good start for the null hypothesis so far.

However, considering outright yields isn’t the correct way to view the effect that QE has had on bond yields. This is because yields are affected by central banks in other ways, the most notable being the setting of the base overnight rate.

The primary determinant of the level of the yield curve is the base rate. In normal times the yield curve will then exhibit a slight upward shape, reflecting the increasing “term premium” that an investor should receive for taking more interest rate risk in longer tenor bonds. The term premium is earned by investors as an offset to the greater price volatility experienced for every Dollar invested as the maturity of a bond is further away.

The term premium is only visible in an obvious way when a central bank is expected to keep the overnight rate steady in the near future. This is because the yield curve not only contains the term premium, but it also captures the future path of the overnight rate set by the central bank.

It’s in the shape of the yield curve that the real effect of QE can be found.

Explaining the yield curve

The future expected path of the yield curve is the dominant reason for why different yield curve shapes seem to repeat themselves in different economic environments.

When it is becoming more obvious that an economy is heading towards recession, the yield curve tends to invert, through a process known as “bull flattening”.

“Bull flattening” is where the yields on the longer-end of the yield curve fall more than the shorter tenors, to the point where the curve can invert where bond yields on longer term maturities can be less than short-term yields.

This is saying that forward interest rates (or interest rates expected in the future) will be lower than what they are today. We all know the yield curve that defines the interest rate for an investment over that period. By using some mathematics, we can convert that yield curve into what we expect interest rates (say 1 year interest rates) at each point in the future.

The steeper an inversion is, the quicker these 1 year forward interest rates will fall. It’s a useful way to know what the market is expecting in the future.

The key here is that it is a market expectation. It is not set by the central bank, it is set by the myriad of market participants who buy and sell bonds and derivatives that affect the shape of the curve, and thus the future expectation.

Investors who are buying a 10-year US Treasury bonds require a view on whether that future path of interest rates will end up higher than the yield they are buying at or not. If they think it will be higher, then the current bond price will be too high and they will have to wait for better levels.

The shape of the yield curve is what QE theory says should be affected, with the aim being lower yields relative to the that central bank’s choice for the overnight rate. These are two distinct policy levers, and you can only consider once you eliminate the effect of the other.

Does QE affect the yield curve?

Analysing the changing shape of the yield curve should give us a better look at the effect of QE on bond prices.

If QE was effective, yield curves should flatten as the central bank is buying the long-end of the curve, driving down yields relative to short rates (which may or may not be cut at the same time).

This is what most think QE is meant to do. It should ease financial condition by bringing down rates and making funding cheaper, therefore stimulating the economy.

With that in mind, let’s look at the results.

The outcome, as shown by the chart above, is the exact opposite of what you would expect. Curves steepen rapidly in the first 6 months of QE, and flatten viciously during periods of QT.

These findings are unanimous, and even apply during the periods of “Yield Curve Control” (YCC) in the US. The explicit aim of the YCC is to flatten the yield curve through purchasing long bonds and selling short bonds. Despite the direct and intentional attempt to flatten the yield curve, it couldn’t even do that!

The opposite-to-expectations behaviour by the market requires an explanation through other means, encouraging us to look past the actual effect of bond buying, and what the actual underlying intentions are of an operation like QE.

QE is bond buying, but that doesn’t really matter

Most people focus on the pure operational aspect of QE, being the bond buying. Net-net, the argument goes, a large buyer of bonds is entering the market, therefore bond prices should go up and bond yields should go down. This isn’t to mention the ridiculous size of the Fed balance sheet! Surely that has an effect too?

To evaluate this view, we have to investigate whether the size of the purchases by the Fed has a significant market impact.

The answer, by a number of measures, is likely not (in normal market environments).

The chart above describes the average daily traded volume of physical Treasury securities by month.

At its fastest pace, the Fed bought $100bn a month in bonds under QE. Yet physical bonds traded somewhere around $550bn PER DAY. The Fed’s influence begins to look irrelevant, and gets worse once you consider the size of the derivative market that sits on top of the physical market.

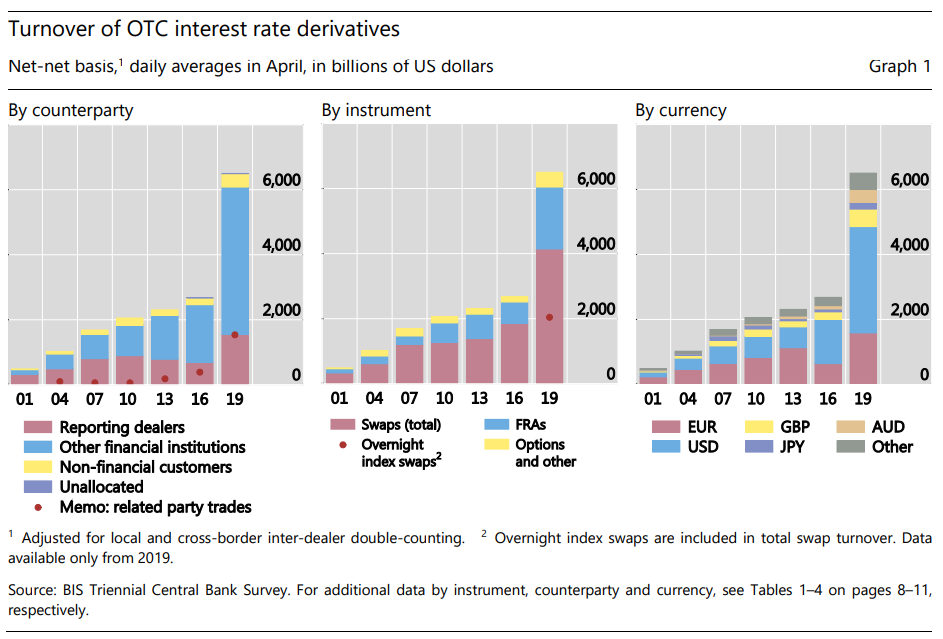

The chart above details global turnover of interest rate derivatives. Derivatives on USD based interest rates (all based on the US Treasury yield curve) make up 50% of turnover, or $3.3 trillion. That figure is a PER DAY amount.

These figures absolutely dwarf the effect of Fed buying, with the possible exception of March 2020, when pandemic panic hit markets. This month likely resulted in an outsized effect on lower yields and a flatter curve, as the Fed competed with nearly everyone else for high quality collateral.

Outside of the panic led markets of March 2020, it’s hard to see how Fed buying had much price effect on markets, making curve steepening an entirely probable event.

If QE isn’t bond buying, what is it?

To understand why QE steepens curves, we need to go another level deeper than just the operational manifestation of QE.

For this I can offer a number of explanations, each as likely as the other. These factors are impossible to test individually, and are part of the magic that makes up the behavioural psychology of markets.

#1: The bond buying is priced in well before it happens

Markets are forward looking. Yield curve inversion precedes the expectation of easing. This is true when interest rates are cut to the point where equity markets are encouraged enough to start rallying again which also steepens yield curves.

For every case of steepening during bond buying, the period before is defined by an aggressive flattening of the curve, sometimes even to the point of inversion. QE has generally only come when interest rates have already been heavily cut, muddying the waters concerning which factor is responsible for the subsequent curve steepening.

#2: QE is easing, and easing is a yield curve steepener, always

This explanation is the simplest of the four.

Monetary policy easing is always a curve steepener. The more rate cuts are delivered, the less inverted a curve will be as the short rate gets closer and closer to the lower yields at the longer end of the curve.

QE is just more easing. It is meant to provide accommodation to the economy like lowering interest rates does. While we aren’t sure how that exactly works (see #4), it may lead the market to think less interest rate cuts are needed than without QE. This has the effect of curve steepening as the yield curve doesn’t need to invert more for lower rates.

QE might be the reason that the Fed never had to make the journey into negative rates like the ECB did.

#3: Interest rate risk removal excites risk markets

While the bond buying effect through QE might be muted to non-existent, there is one aspect that is real, and that is the removal of interest rate risk from private markets by the QE mechanism. By locking up a bunch of long duration assets, the market, with a certain requirement to take on risk, will have to look elsewhere to obtain that risk.

This could possibly cause credit markets to perform more than they otherwise would, as risk taking follows where the risk is available to take.

This can have a cascading effect, working its way down the capital structure through debt to equity.

#4: Call it accommodation, and the market loves it no matter what it does

The last section is related to behavioural psychology of markets and perception versus reality.

I haven’t seen much evidence how QE eases monetary policy, so it’s worth asking the question of whether the efficacy of any moves in monetary policy are even relevant at all.

If the market merely perceives the effect of QE to be positive on the economy, then that should be enough to engage “animal spirits” and make the belief self-perpetuating? This is especially true with action that sounds so large in absolute terms (buying $100bn) and total perceived effect ($9trn Fed balance sheet size). While these numbers can be debunked in terms of their effect (especially the Fed’s balance sheet size which is mostly unrelated to QE) the predominant belief is all that matters.

I’m a strong believer in this explanation mostly because of the forward looking aspect and herd-like nature of markets.

Does QE even prop up equity markets?

I’ve raised a number of questions in the prior section about how QE affects risk assets such as equities and high-yield credit.

There is no doubt that the announcement of a QE programme seems to time with a market bottom in both asset classes some of the time, with the most notable being during QE1 and QE4.

It certainly does appear that large scale QE lifts equity prices over the longer term as well, especially once you include this shorter-term disaster recovery period. The famed equity rally of 2020 and 2021 seems unmatched in history, and regularly gets attributed to QE and zero interest rates.

Let’s look more closely over the longer term. Does a persistent QE programme actually increase equity returns? Or is it only useful as a panacea to a panicking market?

The table above catalogues the return of the S&P500 total return index in every QE, QT and regular time period by official start and ends days of each programme.

What are the results? At first glance it is a open and shut case, with periods of QE easily seeing higher equity market returns. There are a few data points that refute this, however.

The biggest return on the table was during the “QE4” episode, at 31.77% per annum. This is the period most people focus on when lambasting QE, since the market rally out of the pandemic and over 2021 was so strong.

This will be contentious, but it’s disingenuous to consider the “QE4” rally to be entirely down to the Fed buying more bonds. The recovery from the pandemic low was also due to the support extended by governments, which was enormous. Taking the pandemic equity drawdown out of the mix, annualised returns over “QE4” fall to 13%, much more in-line with other periods.

Considering the market movement from the pre-pandemic high may be unfair, however. Another method is to merge “QE4” with the “Reserve Management” period (in which the Fed had to start expanding bank reserves after pushing QT1 too far). Both periods involved expanding the balance sheet and bank reserves, it’s just that the “QE4” period accelerated this buying. Doing this sees the per annum return fall to 23.4%.

“QE1” also saw a large return, but I would make the same argument here as with “QE4”; the equity market benefitted from a very large backstop provided by the American taxpayer in the form of TARP supporting the banking system. To assign the reason for the market rally to QE alone is a difficult proposition.

Periods with balance sheet contraction (periods “QT1” and “QT2”) offer well below average returns. It is worth noting that both of the periods also saw interest rate hikes, and a slowdown in economic growth.

This leaves periods with neither QE or QT. Returns were OK during these periods, at 5%, 10% and 17% respectively. Lower than during periods of QE, but not substantially so.

Chaining the periods of QE generates an annualised return of 19.94% per annum. The 1990s, a period notable for its lack of any QE type policies, generates per annum returns of 18.2%, with the added factor of not starting its measurement period from a market nadir, although it did end it during the dot-com bubble (which you could argue is not too dissimilar to the end of the “QE4” measurement period).

It was the 1990s that saw price-to-earnings expansion that generated these outsized returns, but we haven’t seen this in the post-GFC period at all, with P/E ratios staying in a reasonable band, well below the post dot-com bubble reality of the early 2000s. While the post 1990 period is elevated relative to the rest of history, within this context it is perfectly normal.

If price-to-earnings isn’t expanding then it must be that performance of equity markets must has been matched with earnings growth, and therefore unlikely that prices were “frothed up” by anything related to QE.

I just can’t find any convincing evidence that it was directly responsible for anything related to liquidity or enhanced risk taking or any other of the myriad excuses that seem to be thrown around when trying to explain bullish equity markets.

The reality is that it isn’t QE which has driven markets – it is, as always, about debt.

Earnings growth when economic growth is poor is always about new debt

The enormous government response to closing economies during the pandemic supported economic growth and benefitted earnings growth of the biggest companies with the biggest reach. This is fact.

We can estimate how much this help added to GDP growth by taking a view on when the economy started producing again at its pre-pandemic level (I estimate this a mid-2021) and seeing how much higher GDP growth was at that time.

GDP growth turned out to be 6.2% higher than the pre-pandemic high by re-opening in the second quarter of 2021. This compares to the expansion in US government debt, which was 10% greater than what the trend would have suggested at the same time.

It is irrefutable that the US government elevated GDP growth directly through deficit expansion. This made its way into the stock market, which had two separate forces driving earnings growth – base effects and the debt-affected strong GDP growth.

Base effects are illustrated in the chart above, with large downgrades in 2020 being reversed and then propelled higher in 2021.

2021’s earnings growth only marginally beats out 2010, another year that benefited greatly from the government’s profligacy. Deep equity market drawdowns before both periods also help to make the subsequent equity rally even more supercharged.

The moderation in 2022 earnings shows that the modest uplift to P/E’s by the end of 2021 was a result of misplaced expectations, something that befell the S&P in 2011 as well. This is more likely that QE driven froth.

The chart above illustrates the huge uplifts in public sector debt to GDP just before the two highest returning QE periods. If QE had an effect, we could only be sure after disaggregating from the effect of fiscal stimulus.

This ties in very closely with a previous newsletter where I speak about how it is government that suppresses volatility and drives up asset prices. It usually works very well, however the size and lack of tact with which they expanded debt over the pandemic has ended up causing a situation where volatility is now elevated, primarily due to the Fed’s reaction to high inflation.

What QE really did

QE, and in fact an sort of extraordinary monetary policy, damages a central bank’s reputation far more than any actual positive effect of that policy.

I don’t think that the intention of using QE was to cause any damage, coming about due to the fear of what could happen if they didn’t do everything they could. This attitude forgot one of the golden rules in the finance, however.

Any and all financial engineering requires high levels of trust. The more complicated the financial engineering, the more trust is necessary.

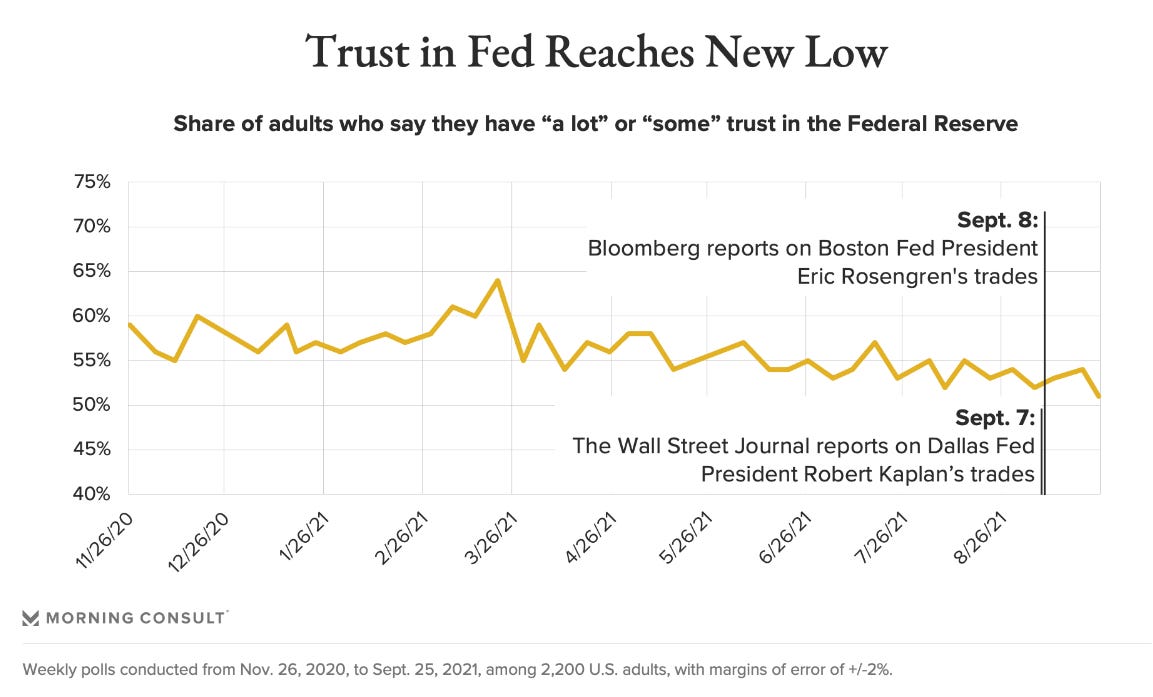

Financial engineering that is perceived to do more harm than good erodes trust. This is what QE has done, as it has been the perception and the narrative that has taken over from fact. The chart below illustrates this, despite the poll being taken at the height of the 2021 equity rally.

The cost of a fall in trust may have been fine if QE did some tangible good. At this point I struggle to see where that is. Some will say that it allowed the government to fund itself, however this reveals the misunderstanding of how the commercial banking system works. This will be a topic for a future newsletter, however read the thread below to get an overview of how that actually works.

QE was and is nearly useless policy that does more harm than good. That harm may not have been in elevating financial market valuations, but through the public relations effect on the Federal Reserve, something that could have serious effects on the future and how they are forced deal (or not) with the next crisis.

Thanks. Great piece. There is an endless holy war about the effects of the QE/QT among all kind of pundits and talking heads. The questions. If “While the bond buying effect through QE might be muted to non-existent, there is one aspect that is real, and that is the removal of interest rate risk from private markets by the QE mechanism” why can’t we think that the removal of rate risk will be same not existed i.e. there is much more risk to absorb in private markets then the capacity of QE to absorb it? Or it all goes through behavioral perception on that removal? So is it correct to state that QE really allows the Fed to ease monetary policy and to avoid using NIRP but it works it’s way through market participants’ perception and like homeopathy?

I had to read this twice. Thank you to the Count for the time required on this thoughtful piece. One thing I might add is to look at Cyclically adjusted PE ratios, not 1 yr forward (I think this article used the latter) and perhaps at estimates of US aggregate profit margins over time (i.e. have margins risen due to QE or due to efficiencies from technology). What we all are thinking about now is what happens next: Will the Fed take actions that cause LT rates to fall, will the affect be the same as last time? It feels a bit different now, perhaps.