The battle between the Yen and the Yuan

It might look like Toyota vs BYD - but it's really about open vs closed

The moves in the Japanese Yen over the last few weeks are, on their own, pretty spectacular. A large amount of the move can be described by just pointing to interest rate differentials - which is to be expected with such divergent monetary policy.

If you’ve kept up with my posts on X, you’ll know that I find the relationship between the Chinese Yuan and Japanese Yen to be far more interesting. The performance of this FX pair is so compelling because it captures so much of the narrative around monetary and external policy and the different ways China and Japan achieve those policies.

The move from a rate of 15 post-pandemic to breaching the 22 level in the extreme volatility on the 29th of April is a huge shift in foreign competitiveness on exports – but this only captures a small part of the story.

The pair summarises how competition in high-value exports has pitted the open economy versus closed economy battle on the market screen right in front of you.

China and Japan are the same in one very important way

I recommend reading my primer on how the world order of trade and external balances is the single most important balance that exists for the maintenance of the current economic and monetary order.

In that newsletter I spoke about Japan and China who play incredibly important roles balancing out the US as the world’s main consumer, who in turn provides US Dollars and financial securities for the world to invest in.

To many it appears that the split between deficit and surplus countries reflects the competitive advantages of one group over the other, and to a certain extent this is true.

In the case of China and Japan I would argue that today’s current account surplus is both the cause and symptom of parts of their competitive advantage, especially in its role of supressing the growth of household wealth to help maintain that external surplus into the future.

This is the key observation that links the two close (if not so friendly) neighbours. Digging into how they got there reveals many other similarities between the two economies that are putting them on a collision course, driving the large moves in CNH/JPY.

Is China just Japan shifted by 30 years?

The two countries are more similar than they’d like to admit, with one likely about 30 years behind the other.

Debt was the problem in Japan before the bust, and there is no lack of ink spilled on China’s reliance on debt for its growth model.

After debt, it’s impossible to talk about the two countries without mentioning population growth (or the lack of it). These trends have been done to death and shouldn’t be news to anyone, however it is interesting to see the population growth rate charted against the share of urban population.

China experienced its demographic bonus (as charted by Nomura below) leading into the 2000s. In the 2000s China’s growth miracle was a result of the productivity boost associated with urbanising a large part of population.

Not only did individual workers become more productive working in a factory versus subsistence farming in rural areas, but the very movement itself created demand for infrastructure and housing of which the construction also drove growth.

This mirrors Japan 20 years earlier, with a demographic dividend paying coupled with urbanisation (if on a smaller scale than China given the higher base).

What does demographics have to do with the persistence of a current account surplus? Nothing in itself, but when combined with high debt loads it makes the threat of being put in a position to rely on external capital even more ominous, making the decision to focus on exports by both economies less of a mystery.

China is encroaching on Japan’s markets

If nominal growth was helped with population growth, or if current debt loads weren’t as high as they were, China and Japan possibly wouldn’t need to rely on their export sectors as much as they do.

In the early days of their growth when they could be fairly called “emerging markets”, a reliance on the external sector made sense because it would:

Earn hard currency (such as USD) to fund local investment and capital goods imports;

Supplant local growth with the ability to grow faster in foreign markets; and

Make most use of likely cheaper inputs as a competitive advantage.

While Japan has been classified as a developed market for some time, China, while still classified an emerging market by MSCI, is well past the point of not being able to attract outside capital for investment if necessary.

Adding to that just the sheer size of China means that it has both the geopolitical and financial weight to be on equal footing with most countries classified as developed. How many other emerging market nations fund infrastructure projects in foreign nations as a soft projection of power?

China’s continued focus on supply-side stimulus has driven its export engine over increasing consumption. This export engine is massive now, totalling $3.3 trillion, towering over Japan’s 2021 exports of only $757 billion.

China’s exports have grown by nearly 3 times since 2007, while Japan’s have stayed broadly static, slightly underperforming the growth in the total global export market.

It’s tough to imagine that China hasn’t taken some share away from Japan over that time given the difference in growth rates.

The long-term USD/JPY exchange rate suggests the same, requiring far weaker levels for the Yen to achieve a smaller current account surplus when compared to the 2000s. This isn’t the same export market than it was then, and the reason is China.

China has also moved up the value chain in terms of the composition of its exports, and this is causing the most problems for Japan.

If we compare China’s export in key categories over time, we can see a falling reliance on low value add exports (apparel, footwear), in favour of high value add (machinery, capital goods, transportation).

It’s that last category that has caused the most consternation despite being less than 10% of exports because it crosses over into goods that have significant consumer visibility and employment associated with their manufacture.

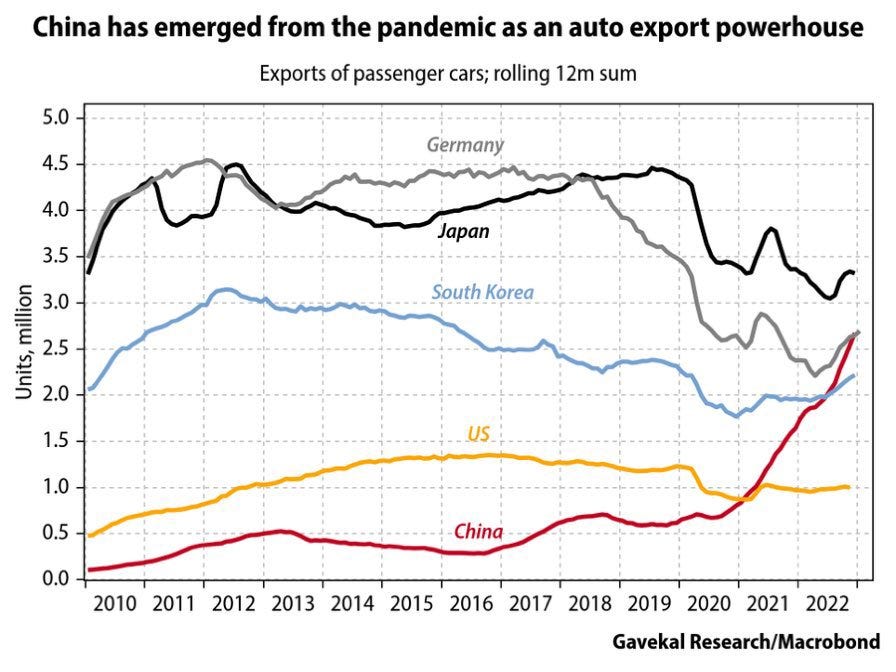

I first pointed out China’s rapidly rising car and truck exports in 2021, and I was surprised at the amount of backlash I got at the time. This was before electric was really on the scene, as cheap combustion cars were flooding most emerging markets, especially in Asia.

This has seen China increase vehicle exports from 1 million to 6 million cars over the last 3 years, with overcapacity in combustion production (reportedly a capacity of 40 million against 15 million domestic demand) driving the need to export.

Since BYD advanced their electric offerings on the global export market, this growth has only increased, and it’s taken away from not just Japanese but also German exports. Despite the overcapacity in combustion production, electric production capacity is still increasing.

Supply-side stimulus is part of the reason for China’s export dominance not only in transportation but in other sectors as well. It is the core reason to why CNH/JPY has moved like it has.

Open versus closed

The movement in the Yen against the US Dollar can mostly be attributed to interest rate differentials, a key factor in described moves in FX markets. Generally, most factor models use the spread between 2-year swap rates in the two countries as an input to a currency pricing model.

The same interest rate differentials don’t apply to Dollar-Yuan exchange rate, due to the managed nature of the currency, that is devalued (or allowed to revalue higher) on China’s decision.

This might make it easy to strike off the reason for why the pair has moved as much as it has by just saying “well the Yuan can’t devalue on its own”, and while this is technically true, it ignores the underlying reasons for why:

It hasn’t yet; and

Why there are good reasons it won’t.

The Yuan hasn’t needed to devalue because China has managed to grow exports despite the strength of the currency - making the advantages of maintaining a strong peg more important for now.

Who needs a devaluation?

Despite countless calls for the next leg of devaluation, we are yet to see USD/CNH shift higher, and it continues to trade in the same tight band since the middle of 2023.

Even though the Yuan hasn’t devalued against the currency of the biggest consumer in the world, and has underperformed nearly every other major exporter’s currency, Chinese exports have continued to rise strongly.

China and Japan share the desire for a current account surplus to avoid the issue of having to call on foreign savings and depleting them; yet China managed to maintain and even grow its trade surplus despite devaluing a fraction of what Japan has managed to with a 30% devaluation. Japan’s trade balance has only now moved back into surplus relative to when USD/JPY started moving meaningfully higher at the start of 2022.

The reasoning behind this is where the similarities between Japan and China end. China can consistently achieve outcomes like this because of the advantages its closed model affords.

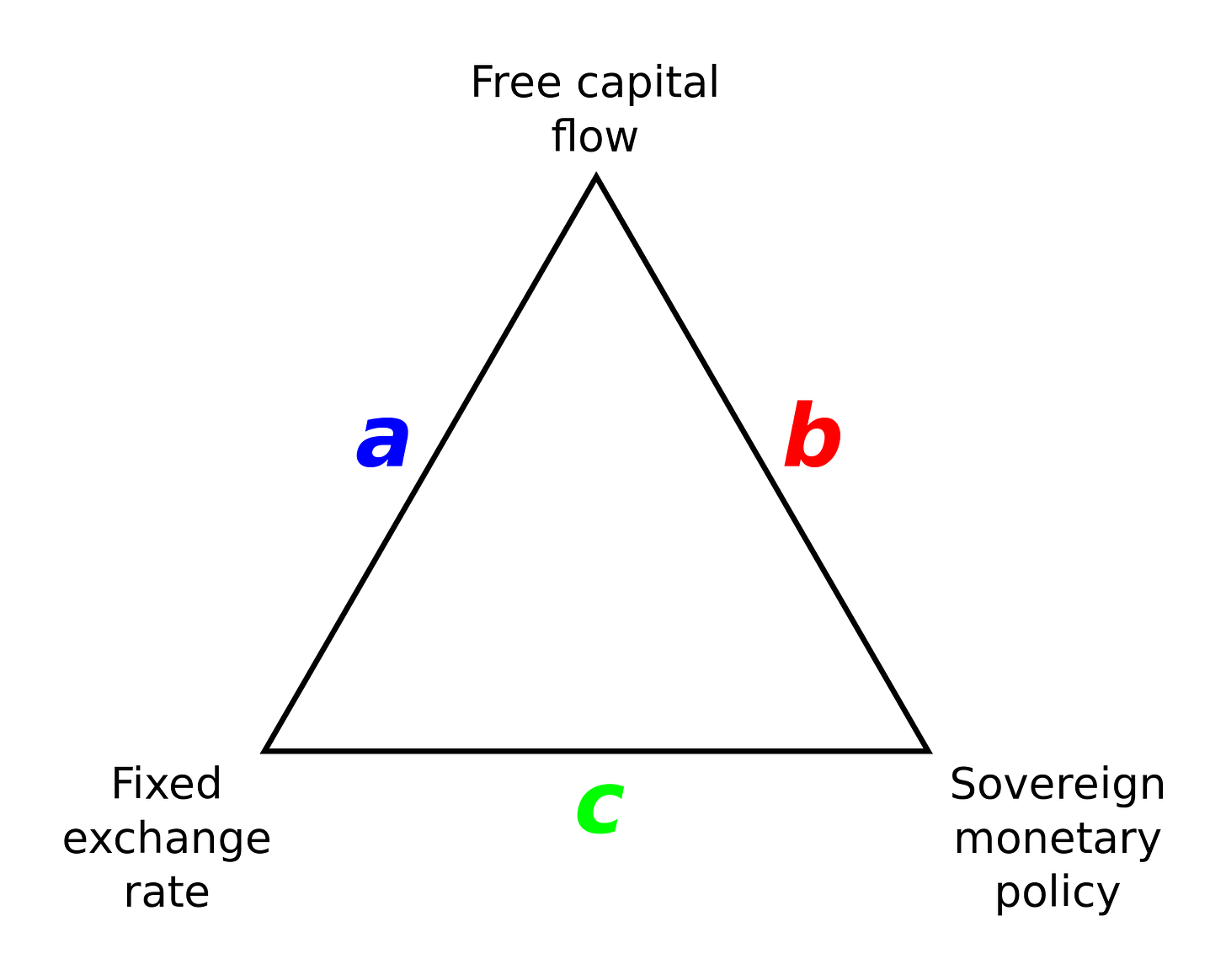

You probably know of the “trilemma” between free monetary policy, free flow of capital and a managed currency. The “trilemma” states that only 2 of the 3 are possible at one time, i.e. you can have fixed exchange rates and an independent monetary policy, but you can’t have a free flow of capital in that regime. This is because free flowing capital will put pressure on the resources of the central bank to prop up the fixed currency which will eventually run out.

China respects the trilemma by closing its capital account and stopping free convertibility of its currency (the reason why the derivative only CNH offshore currency exists). In return it has independent monetary policy and has a managed currency.

I would argue that this trade-off is perfectly fine for China because a closed capital account is no issue if you can generate all the credit you need to power investment internally. With a captive banking system, China is the best in the world at doing this. China doesn’t need an external sector to achieve what it wants internally, so why bother with the fuss and volatility of an open capital account?

The advantages of remaining closed off to the rest of the world and having a captive banking system get even better when you realise with no foreign capital and thus no foreign say about how bad credits is dealt with allow China to do whatever it wants regarding allocation of capital.

These advantages have been used to their fullest extent by leadership in China, and directly explain why they have been able to improve their trade balance despite being relatively less competitive on their exchange rate.

Supply-side stimulus and investment have been hugely successful as well, which not only has helped it climb the technology tree but has been able to do it in a way that has resulted in a far cheaper product than competitors.

As mentioned earlier, the headline grabbing export has been EVs, due to the labour intensity of manufacture of cars and their visibility to general consumers. EVs have the added complication of being the target of politicians for climate reasons, making recent decisions to tariff these imports controversial indeed.

The dominance China enjoys in owning the entire production chain for EVs has meant that it has enjoyed benefits that exceed just the financing for supply expansion. While only a small share of total exports, it has been important in broadcasting the positioning of China on the world stage.

Why not close all the capital accounts then?

There are a laundry list of reasons why maintaining a closed capital account (or fixed exchange rates) are ultimately harmful for an economy and are usually a losing strategy.

Most countries have some form of control over cross-border capital flow. Control over foreign investment through some sort of government board who decides whether assets can be sold to offshore buyers is implemented by most countries. This stops the total free flow of capital.

Outside of this however there is a big gap between a country like Japan and China were only a few regulated entities are allowed to execute a foreign currency transaction in onshore Yuan.

My last newsletter went through in detail how the provision of credit for state directed investment is the primary driver of Chinese GDP growth, requiring the flow of credit (and the production of steel) to continue to make up for a repressed household sector and keep GDP growing.

This strategy, especially since 2009, has displayed an obvious cost. The accumulation of debt by the Chinese to fund this endeavour is a source of much concern. Even if it is sustainable (in that the projects that this debt funded are economically productive enough to cover their interest cost), it forces China to maintain a closed capital account until it is viewed as sustainable internally and externally.

It not all flowers in Japan either

This doesn’t make the case for open capital accounts an easy win either.

The recent volatility in the Yen have made Japanese people far poorer on a global basis than they were previously. In other words, they are less able to consume the goods and services of the rest of the world, because the currency they predominantly earn their income and park their wealth in has depreciated.

Not only does this mean that luxuries like a holiday to Hawaii will be out of reach for many Japanese, but necessities like energy will be permanently more expensive. This isn’t a problem for energy as input to goods that are exported, but it does mean that domestic consumption of energy has to slow.

Despite having a floating currency and an open capital account, Japan finds itself in the same outcome as China in that domestic consumption slows to maintain policy that ensures a current account surplus. Two different paths to the same outcome.

Open versus closed is what is making the currency move – but it is the same mercantilist policy that is driving the underlying economy of both the Japanese and Chinese in the same direction.

By the way – this isn’t a crisis

A sharply devaluing Yen brings all the “doomers” out into the sun, unfortunately. While a persistent current account deficit would eventually erode Japan’s foreign savings and make it call on foreign capital to finance consumption, it is a devaluing Yen that takes it further away from this end game!

A weaker Yen delays any sort of funding crisis by supporting exports in preference for slowly eroding the wealth of Japanese citizens. This is the exact opposite of a sudden financial crisis.

The age-old trade-off

China’s closed policy has maintained the purchasing power of Chinese citizens by pumping the supply side to maintain competitiveness.

Japan’s open and floating policy has lessened the purchasing power of Japanese citizens abroad, but also hasn’t attracted the increase in debt associated with supressing the production costs of their export sector.

The cost for China chasing this policy is in the future when those debts come due (if they ever do). Japan has opted to take those costs upfront through a devaluation of their currency.

Japan could have mitigated those costs by raising interest rates in-line with the rest of the world and perhaps stopping the currency from devaluing as much as it did. Why Japan didn’t do this is because of the symptom of decades of policy that slowed growth and inflation in preference of maintaining an external surplus.

Open versus closed is no different than mark-to-market versus hold-to-maturity; the former lets you adjust to market forces immediately and stop you for building up bigger losses (from greater imbalances) in the future, while the latter stops volatility from locking in losses too early.

Mark-to-market leaves you open to the market overshooting and being irrational for short periods of time, but whether it is irrational or not is only ever clear in hindsight.

Rejecting the information the market gives you can also result in far more pain in the future, when that day comes where it isn’t possible to ignore what the market is telling you. This can be more painful than experiencing even the most irrational market at an earlier time.

Which one wins?

The move in CNH/JPY perfectly captures what happens when two countries have a similar growth model and take two different approaches to achieving it. It’s the underlying policy that is dominant, not the path chosen to get there.

China’s model has allowed a strong external position while keeping the currency strong – Japan’s has devalued the Yen to an improved, if less solid, external position.

Despite being a managed currency, the Yuan is still subject to market forces, which sees the banks and the PBOC needing to defend on occasion, with quite a large defence mounted in April.

A Chinese Yuan devaluation is ultimately a political decision, and I don’t think the politics demands one now. Chinese growth has at least levelled out, and China’s very strong trade position doesn’t require a weaker currency. Leadership will balance this against the downsides of devaluation which include heightened capital outflows, further annoying angry trade partners, and the perception of geopolitical strength a strong currency gives.

For Japan, the pressure on further Yen devaluation has subsided more recently but this has been swapped for Mr. Market forcing JGB yields higher – moving some of the adjustment required away from the currency.

The Bank of Japan can push against this to some extent; by throwing water onto any idea of rate hikes implied by the level of the 2-year JGB. The curve however has more room to steepen and could be the relief valve against further currency depreciation.

At this juncture (and evaluating on a short-term basis), the Chinese model is winning given the goals of both countries. Closed is winning over open, and supply-side expansion is better for an export-led outcome. This will play out very differently in the future.

The lesson

How each approach plays out 10 years down the line is anyone’s guess. Closed will usually win out in the short run but will cause more chaos in the long run.

Ultimately it is the politics and the growth model that follows that puts both countries in the position that they are.

Export-led growth is perfectly fine for a maturing emerging market economy that has natural advantages of cheaper labour and higher tolerance for poorer working conditions. As they climb the wealth ladder these natural advantages disappear, making export-led growth harder to achieve.

Both China and Japan (including other countries such as Germany) have maintained this focus by supressing domestic consumption to create artificial advantages for their export-sectors, each in a different way. They rely on the Anglosphere markets to consume their product to maintain an external surplus.

Much of the reason for this focus is cultural, and larger than economics itself. Continuing down this path will only force more of these compromised outcomes on each of these export powerhouses; ultimately lending to countries like the US to buy their wares and make it appear like they are “saving”.

You be the judge of what the use of savings is when they are being put into the securities of the countries that will perpetually buy from you and you can never effectively call on. They essentially just become numbers on a board, when the real effect is a domestic household that gets poorer relative to the rest of the world.

If you enjoyed this post, please like and subscribe!

That last sentence is a banger.

Both of these are forms of fiscal repression, the Japanese one is simply more market-driven and therefore up-front in allocating losses directly to households on day one.

One quibble: “How many other emerging market nations fund infrastructure projects in foreign nations as a soft projection of power?” Is not, in my opinion, an accurate representation of the BRI.

It is yet another of the innumerable instances in which the Party has found it more palatable to lend abroad to facilitate foreign consumption of Chinese production than to engage in structural reforms that would disrupt employment… in this instance, of the construction materials and equipment sectors. Given the demand to tighten down on domestic credit growth in the housing and infrastructure sectors after Xi’s ascension, there was no other option but to shift that credit growth “off books” by offering credit abroad.