Steel will tell you when to care about China

A proper Chinese slow-down will propagate to US markets through a commodity stoked flight to the US dollar

The decline in the “engine” of the Chinese economy – property – has been precipitous.

Residential property construction and sales have fallen by 50%, leading to a decrease in housing investment (as % of GDP) to fall by 30%.

Investment in residential property along with all the ancillary activity is said to account for up to 40% of the Chinese economy. This hasn’t been news to most investors – the importance of Chinese housing as an asset class have resulted in a decade of forecasts about this being the central factor to the fall of China.

The level of activity and the leverage contained within the system that supports housing investment has been the primary cause for concern. It spreads even further than that, as local governments, through their financing vehicles, were the source of the stimulus for their province which was a large driver of GDP growth in other parts of investment (mostly infrastructure). Land sales to developers were the funding for these vehicles.

So why haven’t these problems affected the rest of the world like they have in the past? The prophecies came true, didn’t they? Large-scale property developers have been defaulting, even those that were previously believed to be “too big to fail”.

Outside of property, China has become harder to read as an external investor. I’ve covered China for more than a decade, and the quality of economic data has never been worse. A quantitative representation reflects this reality.

This newsletter will try to reduce our Chinese indicators that you need to watch, what needs to happen for property woes it to transmit outside of China, and how to trade it when it does.

The mitigation

If you showed the chart of the decline in property investment in China above to an investor 5 years ago and asked what the world would look like if this happened, there answer would unlikely be that US nominal GDP growth is running above 5% and equity markets were at an all-time high.

Part of the reason for this is that the decline in residential property investment wasn’t primarily a result of a lack of demand, limiting the transmission of property weakness into the Chinese banking system.

Housing prices have fallen but not by any of the standards set during the GFC. Secondary property transactions continue to grow, albeit at a slower pace. Housing, after all, is still a key destination for the savings of the household sector in the Chinese economy due to the lack of any pension or retirement wealth aggregation system.

The reason why transactions have reduced from the new housing category is because of the issues surrounding the highly leveraged property development sector. Purchasing a new apartment from a developer involves paying for the full value of the apartment up-front before construction is completed. This was a moderate risk previously, but one that buyers are reticent to accept now.

This makes the decline in demand for new housing partly a demand issue and partly a supply issue. By not being entirely a demand issue, pricing has managed to be stable, and this has ensured that the value of collateral backing trillions of Yuan in mortgages has remained intact. This is important.

Economic growth has also been kept in check through growth in investment in both manufacturing and infrastructure.

Infrastructure investment is straight from the old China playbook of increasing debt to buoy GDP growth. Manufacturing investment has been focussed on autos, resulting in huge growth in Chinese exports of EVs. This has caused China to continue to drive exports higher than they’ve ever been, despite the continued move against this mercantilist policy by both the US and the EU. Restricting Chinese access to these markets has been one of the few bi-partisan issues in today’s politics, however China has managed to overcome this with continued supply side expansion, undercutting western manufacturers.

All of this allowed China to hit 5% real GDP growth targets for 2023 (on the “official” numbers). Continued supply side expansion has created other problems however – from further suppression of household consumption as a driver of growth, to outright deflation.

The compounding debt problem

By concentrating on increasing supply side capacity over local demand, China has fallen into deflation if we use the GDP deflator as the measure.

This has occurred as the total debt burden has risen, worsening debt-to-GDP doubly so, as debt load is measured to nominal GDP.

Most expect the deflator to jump back to positive territory as several one-off and seasonal factors correct, but it’s very unlikely it will grow anywhere near high enough to eclipse the rate of growth in debt.

The growth in debt is being charged by increases in stimulus from the central government, a factor that has been missing in the past due to ideological concerns around supporting frivolous consumer spending, something that has separated the Chinese from western governments since the pandemic.

Despite this, most are expecting the central government to increase the deficit by 2% (to 6%) this year to help growth achieve 5% growth again. This is likely to happen, because private debt creation is struggling to bounce, and the central government is the only place where there is capacity for debt growth. As mentioned earlier, using LGFVs to push growth higher at the province level is going to be tough with property developers in the difficult place that they are. Their capacity (and demand) to buy land to fund fiscal expansion at the local government level is non-existent.

Despite the troubles, the music keeps playing in China, even if it is at a lower and lower volume.

Why hasn’t the slowdown reverberated outside of China?

The slowdown (but avoidance of crisis) has had far different characteristics than it has in the past for developed economies with strong ties to China.

A large reason for this is that things have changed a lot in the last 10 years in terms of China’s ties with the rest of the world.

Debt defaults, especially in the property development sector, have seen foreign buyers of corporate bonds being treated poorly over local holders of debt in restructures. This has seen the amount foreign debt on issue (and weighting in global bond indexes) plummet, reducing any direct financial linkages from China to the west.

The relationship between foreign corporations and China itself has also changed. This is partly from continued breaches regarding intellectual property matters and movements against executives in China under the auspices of “espionage”.

Foreign corporations also don’t have the same exposure to Chinese growth as they once did. Successful foreign companies in China 10 to 15 years ago derived a large part of their growth from the rise in China – this is no longer the case.

However, there is still one pillar that remains in China’s link to the rest of the world, and that is through commodities.

The commodity channel

China is the world's largest consumer of commodities, and the problems in property haven’t seemed to affect this one bit.

While only being 20% of global population, China consumes far higher than this in a number of key commodities. Part of the reason for this is that it is the manufacturing base for the world, resulting in displaced consumption.

This doesn’t explain all of it though, with iron ore imports being one of the standouts. This (along with steel and cement) are directly a result of supply side expansion and construction of infrastructure and property.

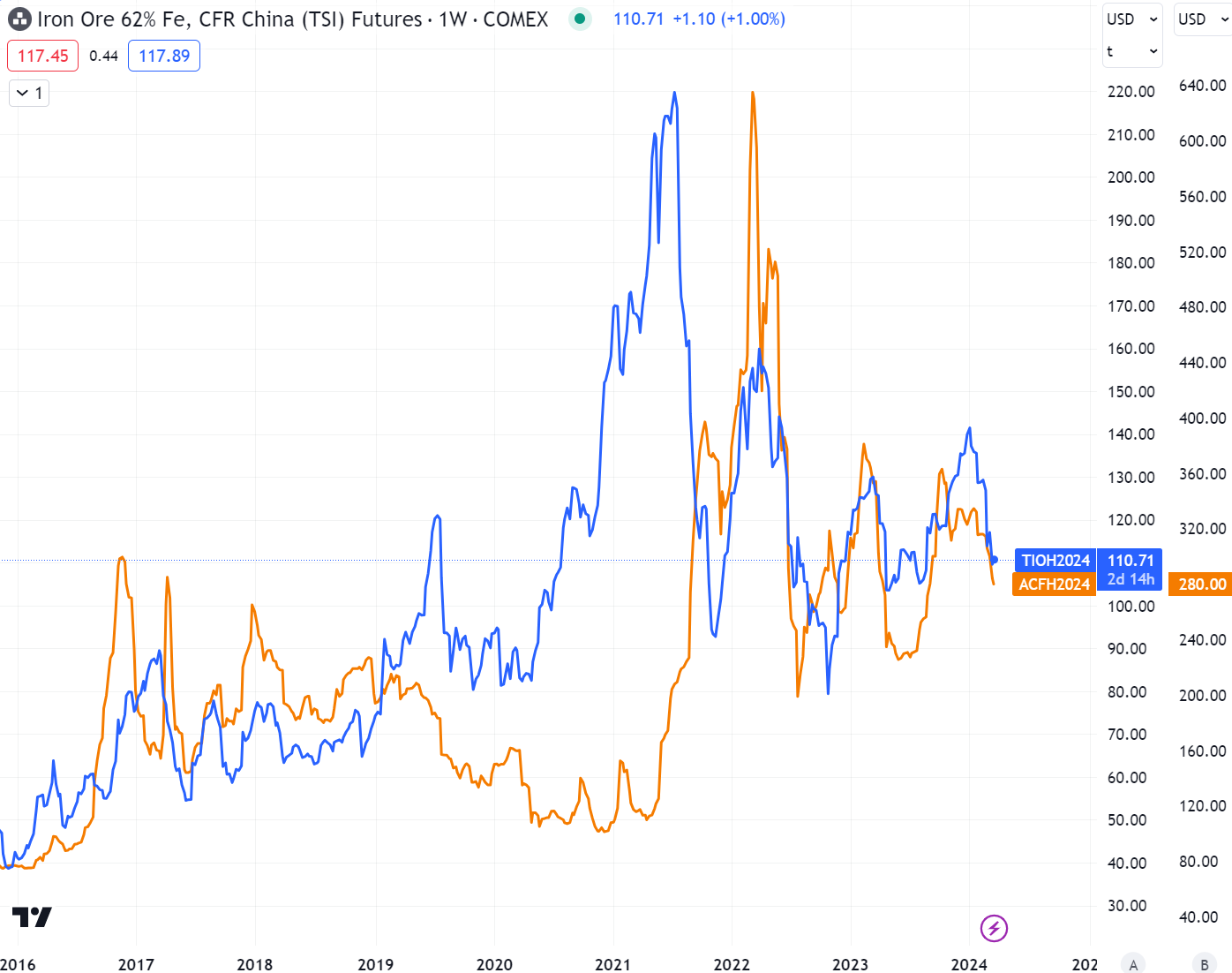

The decline in new floor space started should be seen in demand for steel (especially rebar) contracting heavily, with a decrease in pricing to match. But this hasn’t seemed to have occurred. Steel and its main input, iron ore, continue to trade like it was 2018.

While experiencing some weakness recently, both iron ore and steel rebar futures are trading well compared to the attempted rebalancing of the Chinese economy in 2015. As you would expect, steel pricing in China adjusts to input pricing to maintain steel producer margins at a somewhat static level (and is a big reason for weakness recently, rather than anything related to demand).

The other important input to steel production, coking (metallurgical) coal, has also kept the same relative price chart. At first glance this seems amazing given the weakness in the main sector that drives demand for steel.

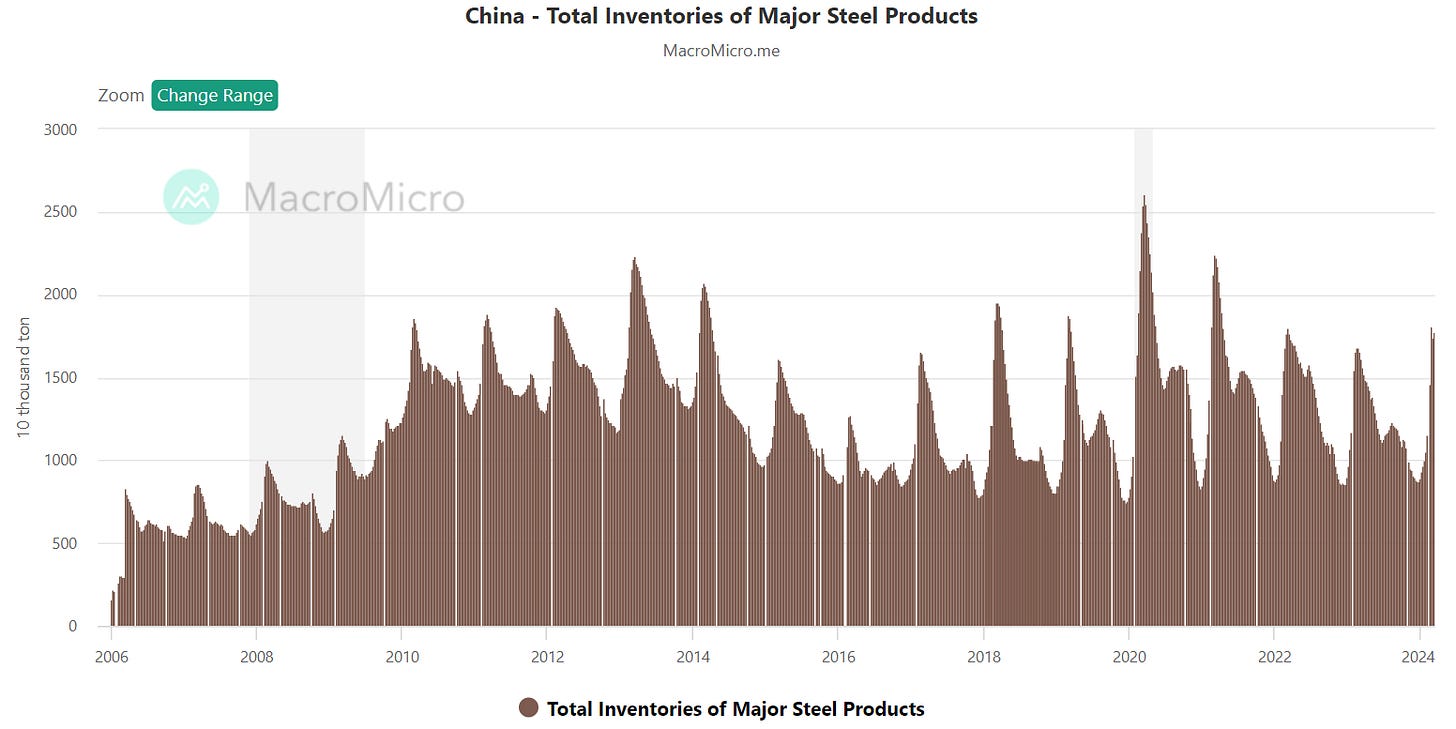

These price charts are well supported by steel production still holding at a level well above that of 2015, even if it has been starting to exhibit some weakness well above the usual January and Chinese New Year dip.

You might think that inventories have been building, but countering these concerns is a normal level of inventory in steel products, adding to the utterly unbelievable story around steel consumption given the collapse in property construction.

There are some micro reasons for steel production remaining as strong as it is. The first is a switch away from scrap metal as a source of inventory, and the second an argument that China has started to dump steel into foreign markets, something that is certain to cause even more issues politically than Chinese EVs will.

The 20-odd million tonnes extra ending up in the export channel this year represents a tiny amount of production, with 2023 marking the first year that total steel production exceeded 1 billion tonnes. Both hot-rolled and cold-rolled product grew by ~7% in 2023, an amazing feat given the backdrop.

Steel industry publications have growth in these sectors slowing to 2% in 2024, citing demand from auto production and infrastructure as key drivers of this demand. Changes to this forecast (and steel production data as a whole) should be your key focus.

These forecasts show how strong supply side stimulus can be, and why China keeps focussing its stimulus towards these areas. Chinese leadership is acutely aware of the extreme leverage it has to steel production both internally and externally.

The steel canary

Steel is so important because it summarises everything about the China growth model of the last 10 years. From property to infrastructure to manufacturing. Cheap steel through expansion of production is crucial to all of these growth drivers.

This is exactly why it should be at the forefront of economic data to pay attention to with regards to China and given the decline in financial ties between China and the west, represents the only channel left by which China weakness can infect the rest of the world.

A decline in steel production, apart from signalling significant weakness in key Chinese growth drivers, would result in weakness in commodity pricing.

Since China is such a large consumer of commodities, this weakness in pricing would start the commodity-dollar spiral that precedes sharp slowdowns in global growth.

How weak commodities affect the US and Europe

Weakening demand and falling prices for commodities clearly hits the biggest exporters of those commodities first, reducing total revenue from production, both on volume and price.

How this reverberates into the rest of the world is through mechanisms that aren’t obvious to most investors and are the inverse of what I described in this newsletter, where I outlined the path for the US dollar if the start of the Ukraine war was actually to result in a commodities super-cycle.

If it was the start of a super-cycle, I outlined how you would receive confirmation of this through a significant weakening in the US dollar because of the inseparable link between commodity prices and the dollar, through the channel of USD-denominated emerging market debt and the pure fact that commodities are overwhelmingly priced in dollars.

If you see weakness in demand for these commodities (including others such as copper) this will put this mechanism into reverse, causing a bid for US dollars well beyond what we are seeing now, despite the fact that the Fed might start reducing interest rates this year.

The dollar/commodities mechanism in reverse

The cycle caused by weakness in commodities demand follows a strict causality path that makes it inevitable.

Price and/or volume of a commodity falls.

Countries that produce this commodity experience a fall in the nominal value of their exports, worsening the trade balance which causes a fall in their currencies versus the US dollar. This is the first leg in US dollar appreciation.

Producers, worried about covering their fixed costs, are incentivised to increase supply to try to get volume to overcome the price effect, further pressuring prices downward.

Commodity companies are overwhelmingly funded with US dollar debt. This puts producers in a bind, as US dollar interest payments start increasing compared to revenues and cause further stress.

This same dynamic occurs at the country level, with emerging market countries exposed to commodity exports will also have debt denominated in US dollars. A fall in their currencies makes the US dollar debt less sustainable, accelerating the decline in their local currency against the US dollar.

Financial crisis due to dollar denominated debt will accelerate the decline in their local currency, especially if US dollar reserves are under pressure.

These effects put a large part of the emerging market complex into recession affecting global demand significantly.

As all of these factors accelerate, capital repatriates to the safety of the US dollar, overwhelming any easing that the Federal Reserve may do as the world economy falls into recession.

This self-fulfilling cycle happens like clockwork and occurs entirely because of the dominance of the Eurodollar market as a funding source for emerging markets, coupled with the fact that commodities (for the same reason) are mostly denominated in US dollars. This process converts commodity weakness into financial crisis which can spread.

This cycle also ignites fear into the market, increasing risk aversion which is also a catalyst for a flight towards safety. While dollar weakness during a commodity bull cycle is a slow process revealing itself in a trend that lasts years, everything happens in a much more violent manner when the spiral of lower commodity prices and a surging dollar reinforce each other in a sharp risk-off move.

2015 is your blueprint

You may have noticed that the price charts earlier all have something in common – they bottom out at the end of 2015. This same trend was replicated across the entire commodity complex as China’s attempt at rebalancing away from debt led growth resulted in collapsing demand for commodities, especially those that had the most exposure to infrastructure and property.

In that attempted rebalancing the spigots were turned off in a genuine attempt to have the Chinese economy stand on its own two feet, rather than relying on a continual form of stimulus which hadn’t really subsided since the GFC.

I’ve written about this growth slowdown in far more detail before, and it’s worth a read to understand the background. Given the strength commodities have exhibited this time around however, Chinese leadership clearly learnt from what happened during this period.

The 2015 episode also was defined by large devaluation in the managed Yuan, ending a cycle of appreciation that went hand-in-hand with the attitude of incorporating China in global trade in a more fair and sustainable way. Europe was still deep in a hole at this point as well, putting external pressure on Chinese exports just at the time internal demand lessened due to the decision to rebalance the economy.

The confluence of these factors coincided to result in commodities trending lower over 2014 and 2015. This shoved the US dollar sharply higher against commodity currencies.

After the bottom in commodities was set, EM currencies turned and recovered their losses against the US Dollar, although not to the same magnitude, replicating their exposure to their relevant commodity exports which didn’t recover to previous price levels after the turn at the end of 2016.

Could the steel indicator be wrong?

There is only one way that watching steel as an indicator would be wrong – China completes a miraculous handover of growth from investment to consumption.

This topic requires its own newsletter, but in short, an engineered shift for the source of GDP growth changing from supply-side expansion to demand-led consumption would need to occur. To achieve this without a severe recession, current debt growth would need to be directed towards consumer demand, and that demand would have to be satisfied locally.

While the central government has warmed slightly to doing this, the sheer volume of demand support needed to replace investment makes any shift unlikely.

This doesn’t fix the problems associated with LGFV debt, or any other debt leveraged into the property market. It also can possibly create an issue with driving China towards a trade deficit, something that it would find very hard to fund.

In short, it’s unlikely that consumption will take over. It was tried in 2015 and the transition is harder now.

This isn’t to mention issues around rebalancing in regard to the Yuan or any other policies that are a result of imbalances elsewhere in the Chinese economy.

Before I write about this, please read Michael Pettis or Martin Wolf on these ideas, they have both (especially Michael) written about this issue extensively.

Commodity weakness translates into financial disaster

The reduction in direct financial links between China and the US are, in my opinion, irrelevant compared to the transmission of financial stress through the commodity and dollar debt avenue.

This is the true and only method by which stumbles in the Chinese economy make its way to developed market equities and rates.

The trade in this environment is clear – own developed market bonds and the US dollar against a basket of emerging market currencies, and then more broadly. Supply has increased for a lot of key commodities, including iron ore (which is set to increase further from African exports in the next few years), so any volume falls will have a stronger effect on price this time around.

The aspect of this that hasn’t been addressed in this newsletter is the prospect of deflationary risks emerging because of collapsing commodity prices. An event such as this would have the power to eradicate any fear that central banks have of the risk to upside inflation, having repercussions of bringing back negative correlation between bonds and equities, causing bonds to rally and curves to finally steepen after the bias to flattening over the last few years of inflation worry.

Would it be enough to bring the Fed to the point on considering zero interest rate policy again? That may only be the case if the US government doesn’t end up increasing fiscal deficits more than they are already. This isn’t too hard to imagine – if they are happy with running 7% deficits at a time when real GDP growth is consistently above 3%, what would they do if growth was at zero?

Simplify your Chinese analysis and stick to watching steel like a hawk. There isn’t any real alarm at the moment with steel production expected to grow this year. If this changes, however, your trading plan should be ready to go.

If you enjoyed this, please like and share!

A very interesting perspective - Thanks. It seems to me that we have crossed a sort of macro rubicon in 2008 (hence the title of your Substack?) Both China and the West appear to be stuck in a doom loop as the debt driven post Bretton Woods period appears to have ended with a bang at the GFC. Both China, the US and Europe are now transitioning to an economic mode of competition that relies on fiscal deficit spending combined with various protectionist measures. I wonder therefore if the commodity/dollar doom loop that you describe might now be somewhat different - As you indicate deflation in commodity prices begets falls in currencies of the producers etc which causes flight to safety of …. The USD?? But post GFC - Is the USD really safe given the increasingly apparent fiscal dominance and financial repression policies now being enacted to address the debt to GDP burden. Would the flight to safety not perhaps be increasingly likely to benefit currencies outside of the global fiat $ (fiscal domination / financial repression) doom loop? Ie.Gold and Bitcoin? Things that governments find difficult to debase and default on that are commodities/currency that are not dependent on economic demand but on financial demand for actual safe financial assets. Sorry to drop the Bitcoin bomb here :-). Thoughts?

Great as always. Thanks.