How long until they say “don’t fight the PBOC”?

China's central bank will have indirect control over Fed policy as it refuses to follow global policy tightening

By choosing to ease policy rather than tighten like the rest of the world, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) will place a cap on the Fed’s possible rate hikes through currency and trade pressures.

The Fed has never really had to consider any other bank in setting its own monetary policy before, but it will have to from now on.

Lower average global policy rates will drive more debt and asset price growth, leading to further imbalances.

You’ve probably heard the trading advice - “don’t fight the Fed”. This previously sage advice has been relevant since its inception in the early ‘80s but it might have finally hit its use-by date, and it’s not a good thing for long-term global stability.

“Don’t fight the Fed” wasn’t just reserved for markets that the US Federal Reserve affected directly, like US Treasuries. The phrase has been commonly repeated outside of the markets that are affected by the Fed directly, recognising the respect for the Fed’s effect on global markets.

Obviously, it still applies for those markets under the Fed’s direct control. Outside of this, however, recent moves by the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) add to nearly a decade of agitation of the status quo. The agitation has mostly been subtle up until this point, but now it’s out in the open for all to see. The PBOC’s move for dominance will bring into question which central bank smaller countries should look towards.

For the first time being “equals” on the global stage, the Fed and the PBOC are going head to head with opposing monetary policy stances over the next year. The Fed, at the time of writing, is broadly expected to hike rates five times next year, lifting the Fed Funds rate to ~1.25%. China, in stark contrast, cut it’s 7-day Repo Rate by 0.1% in mid-January. Whether or not there are more rate cuts to come, the signalling effect of this is immense.

These moves have taken the battle for monetary policy dominance out of the shadows and into the open. Previously it was tough, if not impossible, for any individual nation to move against the Fed when it comes to setting monetary policy. The PBOC is telling everyone that it doesn’t have that issue.

Without the default position being to follow the Fed, the US will find itself with difficult decisions to make. In the past a problem for the US was a problem for the world, so other nation states’ monetary policy would happily move in tandem with the Fed, allowing US policy to be extended onto the rest of the world. China, from this point onwards, through its focus on its own agenda and its sheer size, is bringing this luxury to an end.

The Fed has never been challenged before

The Fed has essentially been the Fed that we know today since the early ‘70s. Before China, the only legitimate competitors since that time have been the Soviet Union, and later on, Japan.

The Soviet Union, whose economy reached 60% of the size of the US economy at its peak, didn’t challenge the Fed on the global stage. Being a communist state it had strict capital account controls and a pegged currency which meant it didn’t compete when it came to monetary policy. Trade was limited to states that were friendly to the Soviets, and the hard currency generated through exports of energy were offset by much-needed exports of high tech items from the West.

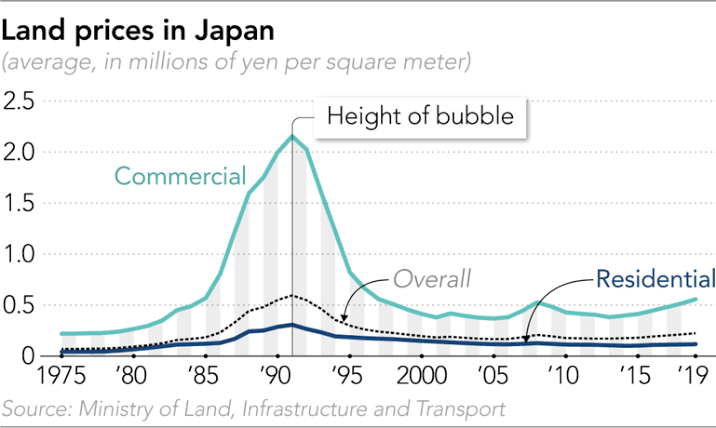

The writing was on the wall for the fall Soviet Union by the mid-80s. Japan was the next challenger. Japan grew quickly in the three decades leading up to its own bubble bursting in the early ‘90s. Similar to China more recently, Japan achieved this through a mercantilist model focused on exports. During this period the Bank of Japan grew in significance as the Yen became a currency that could no longer be ignored. At the height of the boom, Japan’s economy (in USD) was 70% the size of the US.

Unlike the Soviet Union, Japan was relatively open and embraced a free-floating currency. Everything was in place for Japan to be a challenger to the US in size and influence. Japan had a chance to push for economic dominance.

Even before the bust of the Japanese asset bubble in 1991, the chances for the Bank of Japan to butt heads with the Fed disappeared with the signing of the Plaza Accord of 1985.

The Plaza Accord of 1985

The Plaza Accord was signed by the US, UK, France, Germany and Japan in a secret meeting at the Plaza Hotel in New York in September 1985. The Accord outlined an agreement where the US could reduce its trade deficit with Germany and Japan by letting the US Dollar depreciate significantly. Germany and Japan would also agree to rebalance their economies more toward domestic demand rather than exports. The meeting was held in complete secrecy to ensure the most significant market effect on announcement. It’s unclear whether this worked or not, as the US Dollar started depreciating well before the Accord was signed.

And did the US Dollar depreciate! In total, the US Dollar sank by nearly 50%. It worked so well that the follow up to the Plaza Accord, the Louvre Accord, was agreed in 1987 to reverse the Plaza Accord almost in its entirety.

The impressive appreciation of the Yen during that period obviously hurt Japan’s export sector. To counter this the government set about implementing huge stimulus to grow the domestic economy. This, along with irresponsible commercial bank lending, caused a credit bubble which eventually popped in 1991.

Whether or not the Plaza Accord caused the asset bubble to pop and Japan’s subsequent “lost decade” of economic growth isn’t the point here. What is amazing, however, is that countries like Germany and Japan agreed to appreciate their own currencies, which is equivalent to tightening monetary policy by decreasing your competitive position, in favour of a competitor.

In the context of international relations in this day and age, frankly, this sounds absolutely mad. Every country with a slowing economy wants to depreciate their currency and to be rescued by growing exports. This is because a lower currency makes your exports seem cheap to trading partners, making your export sector more competitive. An expensive currency makes imports cheaper, driving domestic demand, which helps to balance a strong export economy.

Why on earth did Japan enter into this agreement? A number of reasons can be cited as having forced their hand. The primary worry of the Japanese was that the US would impose tariffs on imports, crushing their export sector. The agreement allowed Japan to avoid tariffs, while giving them time to rebalance towards domestic, rather than external, demand. This was the right long-term choice for both the Japanese and the Americans, they thought, so signing the agreement made sense.

Ultimately, it was the combination of the Plaza Accord and domestic policy that hurt the Japanese. They never needed to agree to what the Americans proposed, and if they hadn’t, then they could’ve relied on their superior export sector to drive growth.

The Chinese have clearly learnt from Japan’s experience.

The Chinese are refusing to follow the mistakes of the Japanese

The PBOC’s control of the Yuan against the Dollar has been a flash point concerning the US congress since the early 2010s. The US has argued that China has persistently kept the Yuan too weak by avoiding floating it. Managing a fixed currency to be weak is similar in economic effect to running easing monetary policy.

The fear, and then the imposition, of tariffs by President Trump wasn’t enough to scare the Chinese into compliance either. Clearly US officials were angling for a deal given the numerous (tense) negotiations they had before tariffs were imposed. It could well be that the Chinese’s decision to wear the tariffs was the right one, as the trade deficit between the US and China is as wide as it ever has been .

I say ‘it could well be’ that they made the right decision because it appears as if the Yuan has been depreciated significantly against the USD over that time, probably offsetting the tariffs, and more.

The chart above shows the Yuan in a band of 6 to 7 since Trump’s election in 2016, which wouldn’t suggest any meaningful depreciation. We do know, however, that the PBOC has been active in keeping the Yuan cheap by changing bank forex holding requirements, and, more importantly, setting the Yuan to a total of 9% cheaper than the ‘fair value’ basket just in the last year.

It’s quite possible the tariffs didn’t work because the Chinese countered with something far more powerful - currency depreciation. If there was an antithesis to the Japanese approach in 1985, this is it. And it’s for this reason that the PBOC’s moves are such a strong indicator that the fight for control of global monetary policy is on.

The drive to control global monetary policy is driven by survival

They’ll never directly admit a problem, but China has been trying to rebalance away from its mercantilist and debt driven model since the GFC, as if they know that it isn’t sustainable for the long-term. China has wanted to move private consumption from about 35-40% of GDP to closer to the US at 60%. The IMF have recently commented that the rebalancing task has become more difficult as a result of the COVID crisis.

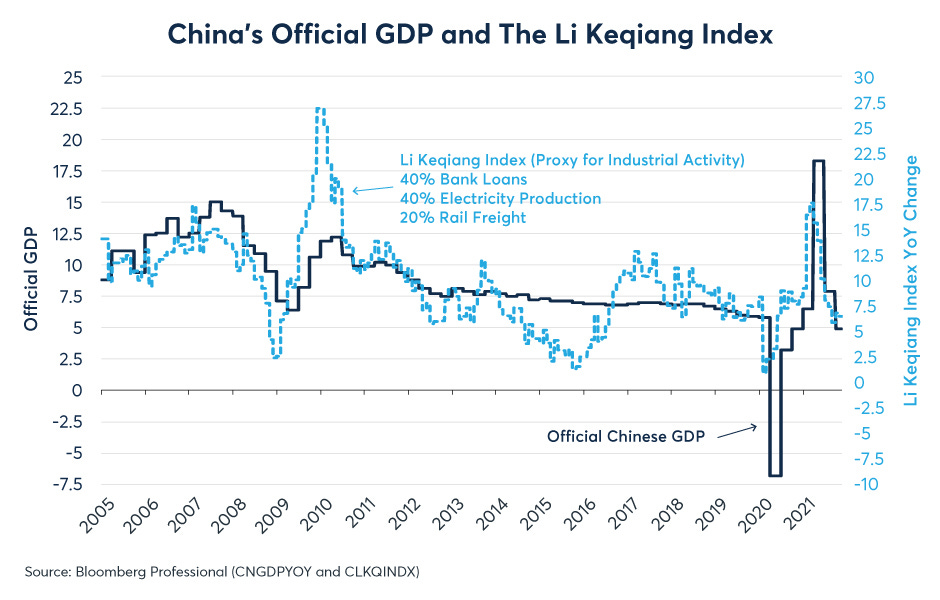

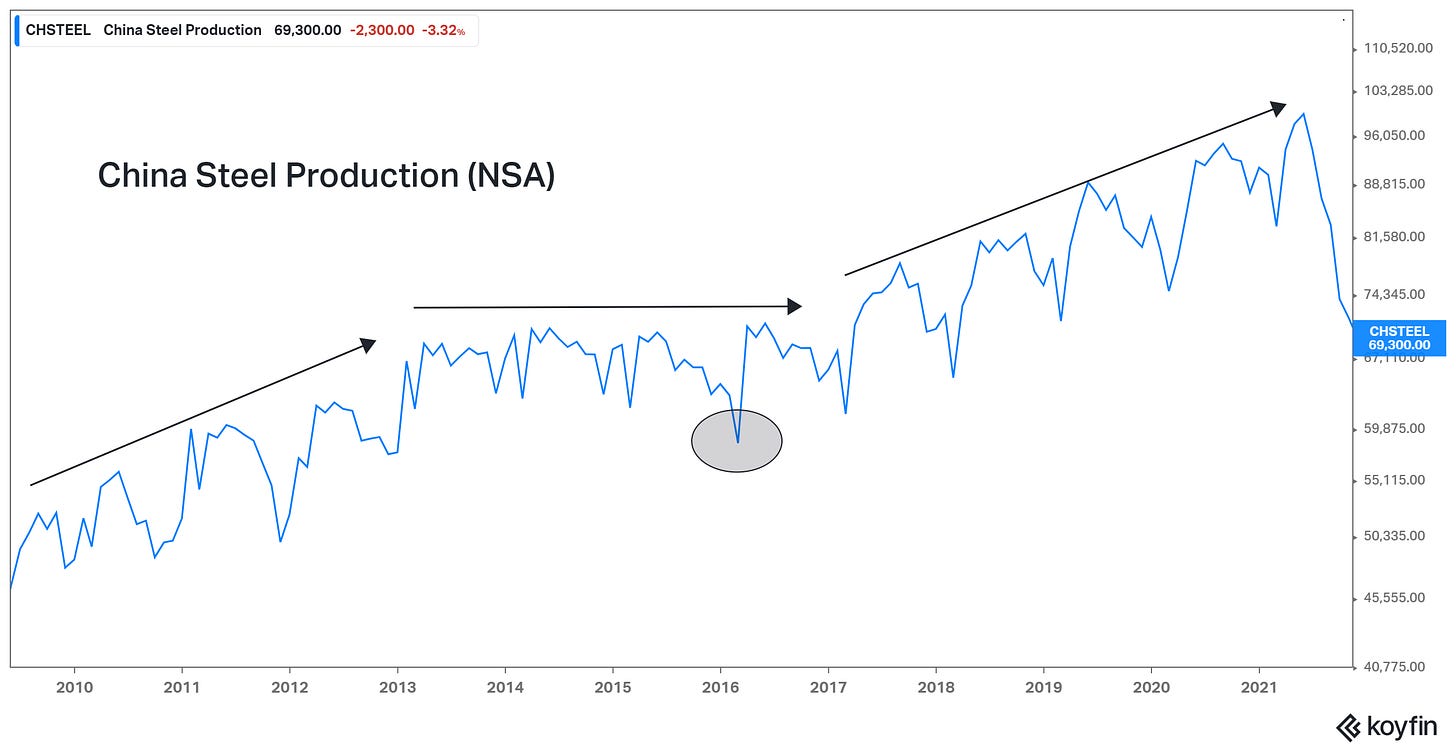

Each and every time China’s tried to fix unbalanced growth issues, things have only gotten worse. The economic downturn of 2014/15 represented the end of the last genuine attempt the Chinese had at addressing reliance on trade and investment to drive GDP growth.

Ten years prior to that, in 2005, the Chinese started to allow the Yuan to appreciate against the US Dollar, which resulted in a large 33% appreciation over the period until 2015. To moderate the reliance on investment as a component of GDP growth, they also reduced the amount of credit creation in the economy through its state owned banks.

The short of it is that this rebalancing attempt didn’t end well. The Li Keqiang index highlights the industrial slowdown that the country experienced in 2014/15, which rippled through the world in the form of plunging commodity prices. Despite the fact that GDP growth remained suspiciously constant during this downturn (hmmm), China’s trade partners really felt the slowdown, as did markets in general. To a panicking market it seemed like the China miracle was over.

Once things got bad enough, in 2015 the Chinese ended the appreciation of the currency and then depreciated it over the next year by 15%. They also turned the credit taps back on, and deployed it wherever they could including building cities that nobody wants to live in and coal power plants that would never be turned on.

This episode of economic downturn is telling. The Chinese didn’t need an equivalent to the Plaza Accord to undertake what it knew to be better for the long term. However, the economic weakness that came about as a result of the rebalancing process was politically untenable. The Belt and Road Initiative didn’t generate enough demand to offset the weakness in domestic investment, and threatened to sacrifice this important piece of foreign “diplomacy” altogether.

This realisation has forced the Chinese government (and as such, the PBOC) into defending top-line GDP growth at all costs, even if it means adopting a short term approach of maintaining a weak currency and continually growing debt and funding investment. More recently, easy monetary policy has been used to offset the effects of dealing with over-leveraged property developers and political issues with the Chinese tech sector.

Competing means moving to a shorter term, and more selfish, focus

So, the PBOC is driven into policy conflict with the Fed out of pure survival, as it is highly likely that economic disaster will follow on any further rebalancing attempt. If China wants to remain a global power, easy policy is a requirement. Economic rebalancing is frankly out of the question at the moment.

At this point you might be wondering why it matters if two large central banks have opposing monetary policies. Surely each can set monetary policy to suit its own needs? To illustrate, consider a world with two countries of similar size, with free floating currencies, and each with their own independent central bank.

If monetary policy moves in tandem between the two countries, their currency exchange rate will remain static, all else equal, as rates are raised. This will leave the exchange rate between the two countries unchanged and the adjustment to rates will only affect each country’s domestic situation.

However, if country A hikes and country B eases, the currency will move, with country A’s currency appreciating against country B. This makes country A less competitive and it will experience a slowdown in exports to country B.

The difference in monetary policy will mean that country A will experience a slowdown in domestic and external demand. This slowdown will be more intense than in the first scenario, and country A won’t need to hike as much to achieve the goal set by its central bank (which may be slowing inflation, or anything else). Country A’s competitive position would be highly compromised.

As a result, country A’s policy rate will reach a lower ceiling as a result of country B’s decision to ease. This leads to the danger of everyone running monetary policy that’s too easy, stoking debt growth and all the issues that come with that.

The core issue for the Fed having a real competitor for the first time in the form of the PBOC is that their ability to run tighter monetary policy is now restricted. If the Fed wants or needs to tighten, they just don’t have as much flexibility anymore.

The upshot of this is that any countries that for whatever reason wanted to have strong currencies would find it easier to do this. However, outside of countries currently in a currency crisis, these are few and far between.

Competitive currency devaluations are dangerous as any notion of prudent monetary policy has to be thrown out the window in favour of doing whatever is needed to preserve your competitive position globally. If you believe monetary policy has a role in managing price or asset inflation, this is a concern.

The PBOC will win because easing is easier

While this is the first time the Fed and PBOC have diverged on short rates, China has many other tools to ease policy. The most notable are through the currency as discussed above, and by the RRR (Reserve Requirement Ratio) which sets the amount of reserves the bank need to carry against their loan books. Lowering this requirement allows more credit to flow into the economy, easing financial conditions.

In 2017 the PBOC hiked short rates with the Fed, and in 2018 started easing with every other tool it had. This subtlety is no longer present today.

This is helpful for understanding the divergence in 10 year bond rates in both countries in 2018. The PBOC lowered the RRR early in 2018, while simultaneously devaluing the Yuan. The China 10 year bond yield fell in response to this easing, countering a Fed that was only in the middle of its multi-year hiking cycle. Despite the Fed’s hiking, US yields eventually fell in sympathy.

In this case, the Fed misjudged the amount of hiking for the US economy in 2018/19 because of the PBOC’s easing. The old rules do not work anymore, and the market should take heed of this.

The Fed has to now be aware of the PBOC’s stance

I liken competitive devaluation to the behaviour of the US banking system in the lead up to the GFC. Merrill Lynch and Deutsche Bank famously bought into large subprime lenders in 2006 because the profits from this sector were huge, and the management of each bank were being pressured by the market to generate the profits of their competitors. If they felt like that type of lending was a bad idea, it had to be ignored because they were losing favour against their competition that was lending in that space. Short term gain came with long term pain.

The same happens with competitive devaluation. Keeping easy policy is great in the short term, but embeds serious imbalances that make the eventual rebalancing more painful.

The cut to the PBOC policy rate in January marked the end of the Fed being in charge of its own destiny in regards to monetary policy. As such, the market has to seriously think about the Fed Funds rate range in context of what the PBOC is doing. This will be confronting for both the Fed, and the market.

The Fed has been accustomed to being the leader in setting global monetary policy, and has never really had to consider what other banks are doing in determining a path for themselves. Central banks from the Reserve Bank of New Zealand to a bank the size of the European Central Bank have always had to consider what the Fed is doing. To avoid any future policy mistakes, it would favour the Fed to consider the PBOC now, just like those smaller banks consider the Fed.

Whether the Fed works it out or not, the impact of the PBOC on the length of the next Fed tightening cycle is a certainty.

Great article. I have been thinking the same thing as you.

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4453669-the-fed-needs-flexibility-to-factor-in-both-the-american-and-chinese-versions-of-common-prosperity