A new commodity bull market must come with a weak US Dollar

Commodity cycles are the main determinant for long-term US Dollar trends, relegating the influence of the Fed to short-term wobbles only

Over the decade long cycle window, the US Dollar trades inversely to commodity prices. It has done this consistently since the end of Bretton Woods, and will continue to do this for as long as commodities are priced in US Dollars.

This mechanic is driven by commodity producer economics, which drives differential growth and capital flows in a causal relationship.

If this is the start of a new commodity boom cycle, the top for the US Dollar may be set at the peak of this Fed hiking cycle.

The “petrodollar” is not an advantage to the US, it’s a burden. Any country that wants to take this burden on must have the economy and military to back it.

The invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in February 2022 has abruptly ended a prolonged (and rare) period of peace in Europe.

This period of peace has made us forget about the realities of our need of resources for modern society. Tech, and all the evangelism associated with it, does not solve the need for base commodities. In fact, it drives it.

This base (some would say primal) need means that commodities cannot be separated from geopolitics. What follows from this is that you also cannot separate the global monetary system from commodities. The last month has reminded us of that.

Since the global monetary system is dominated by the US Dollar, and the global monetary system is so closely tied to commodities, the US Dollar is intrinsically linked to commodities – with commodities trends being a key determinant of the direction of the US Dollar. This view isn’t widely held or understood, despite the explanation for it being clear.

Geopolitical events tend to define turning points in the trend for the US Dollar, which instead ends up dominating our focus. These points in time involve a “passing of the baton” for economic growth from the US to somewhere else in the world. Commodities are always involved in this shift.

Further, the market tends to get distracted by short-term swings, which pull attention away from long-term trends. Within these smaller cycles can be seen influences from divergent monetary policies. Monetary policy changes are among the events that can flag the start and end to a long-term commodity driven cycle.

If we are in fact in a new commodity bull market, the relationship with the US Dollar once again will become apparent, and it is important to understand why.

It’s only worth talking about developed market currencies over long horizons

Short-term currency trading is a fool’s errand. In my career I’ve never met a trader or analyst who has consistently made money trading developed market currencies. Those that have succeeded have limited their trading to crises, when risk premium re-emerges.

At the quarterly to annual scale however, the factors to price moves become more obvious.

The key factors are:

GDP growth differentials;

Interest rate differentials; and

Capital flows.

This might seem obvious, but it’s the next step in thought that really simplifies these factors into one overarching/fundamental driver of the US Dollar akin to a unifying theory in physics.

For the US Dollar, all of these factors can be boiled down to the direction of commodity prices. This relationship is special to the US Dollar, and isn’t shared by any other currency. It is not due to the fact that the US is a large consumer of certain resources as the correlations don’t change when the US is a net exporter of oil, for example.

The Euro does not have the same relationship with commodities for one simple reason – commodities are overwhelmingly priced in US Dollars.

Pricing commodities in US Dollars ensures that the three factors mentioned above are all reflections of the trend in commodity markets. Growth differentials are due to commodity strength, which flows to interest rate differentials, and which finally results in capital flows.

When commodities are strong, the US Dollar is weak as producer economies outperform the US. Due to this, they set interest rates higher, and strongly attract capital away from the US.

When commodities are weak, the US Dollar is strong as producer economies underperform. They then set interest rates lower, and lose capital to the US safe haven. US Dollar based borrowing in these countries will sometimes precipitate a crisis at the same time as a strengthening US Dollar makes it harder to repay loans.

No other economy has this “exorbitant privilege” that gives the US a unique status for relative capital flows. Part of this is due to its reserve status, which in turn is the reason why commodities are priced in US Dollars in the first place.

Why the denomination of commodity pricing matters

The key to understanding the link between commodities and the US Dollar is the fact that most commodity producers have costs that are in their local currency, while all their revenues are in US Dollars, the currency in which most commodities are priced.

The value of the global commodity market is tough to nail down, but it is in the region of $6-8trn per year once you include energy, metals and agriculture. Clearly this is a significant amount of activity.

Most commodities are bought and sold using trade finance, with banks operating as intermediaries between buyers and sellers of commodities, providing short-term finance, and also acting as a sort of escrow facility, only paying out funds once delivery has been completed.

The GFC saw severe issues with the flow of trade finance, heavily impacting commodity trade (and broader trade in general). This flow of credit extremely important to the functioning of the global trade system, with the US Dollar having the only offshore market (aka the Eurodollar market) that is large enough to support it.

Trade finance banks also provide the ability for producers and consumers to hedge their exposures. This is far more important for producers than consumers, as consumers can ultimately pass on any price changes to customers, whereas producers have fixed costs to cover that are mostly in the currency of the country where production occurs.

Commodity related currency flows kick-off the counter-cyclical moves in commodity prices and the US Dollar.

When commodity prices are rising, producer transactions in US Dollars are to sell, and in increasing size.

The size of the commodity market precipitates an increase in the size of the Eurodollar market. This forces the US to run a larger current account deficit to create Dollars in the form of debt for the offshore market (why this is the case is a topic for another newsletter). This is part of the exorbitant privilege (or burden, depending on your point of view) of having the world’s dominant currency. A larger current account deficit will slow US growth relative to the rest of the world, creating a relative economic growth benefit to producer nations.

This differential encourages capital flows into the producer nations, partially due to the opportunities available through investment in commodity output, but mostly due to higher growth and likely higher domestic interest rates. This boosts producer nation currencies at the expense of the US Dollar as well.

The sum of capital flows and commodity trading form a self-fulfilling cycle. They can also work in the other direction, where a weak commodity complex causes the Dollar to be stronger on a relative basis.

The trends are faster in the case of weak commodity prices because the cycle will exhibit the same links, but in an accelerated manner. Producers, worried about covering their fixed costs, are incentivised to increase supply to try to get volume to overcome the price effect, further pressuring prices downward.

The theory I advance here is that changes in commodity prices cause an inverse movement in the US Dollar. Others believe the causal link is the other way around: that movements in the US Dollar cause commodity prices to rise or fall. My view is that it is the demand for commodities that is the more impactful trigger for currency fluctuations, rather than that currency changes have the major impact on commodity trading.

With this information, we can know go back through history and see the correlations.

The 5 Dollar cycles since 1971

Since the move away from Bretton Woods and the gold standard in 1971 the Dollar has been through 5 major cycles with my assessment being that the last one finished in mid-2020. Here is a quick breakdown of each, highlighting this important relationship. For the comparison I’m using the Goldman Sachs Commodity Index and the DXY Dollar index (see trading notes at the end for further details).

A common theme which we will discover is that each cycle is punctuated by a major event, whether it’s recession or major policy changes or geopolitical upset. These events can result in mislabelling of trends and can detract for the real underlying cause that is already forcing the hand of the market.

#1: Bretton Woods until Volcker

This decade was plagued by so many problems – detailed in my last newsletter, which discussed the sources and reasons for inflation in the ‘70s.

The obvious driver of commodity prices here was the Arab oil embargo which tripled prices in 1974 and then the Iran revolution which doubled prices again in 1978.

The end of Bretton Woods had a little-known effect on this relationship. Ending the fixed currency regime allowed the US to run larger trade deficits, a problem which was appearing in the ‘60s as European and Asian exporters became more competitive. As mentioned earlier, a larger current account deficit is a necessity in a strong commodity market.

Whether you credit Paul Volcker for breaking inflation through aggressive monetary policy tightening, or a fall in oil prices due to abundant supply in the early ‘80s, by 1980 the 10-year run in commodities was over, as so was the weakness in the US Dollar.

#2: Volcker until the Plaza Accord

Commodities plunged early on as oil became abundant, and the Dollar rallied strongly as the US ran increasingly large trade deficits.

You might be wondering why this period is the weakest for illustrating the link between commodities and the US Dollar. In this cycle the GSCI index is affected by its construction by having a lower weight in oil, the key seaborne commodity at the time. This has an impact because the ‘80s was a rare period in which energy and non-energy commodities had an inverse correlation, and is why the relationship doesn’t hold as well. Correlations are fairly static across both sectors in all other periods.

#3: Plaza Accord until the rise of China

The sell-off in the Dollar after the Plaza Accord agreement was coincident with a large rally in commodity prices.

While the third cycle I present was from 1985 to 1998, the commodity rally was over by 1992, with prices tracking sideways until 1998. Both the commodity index and the Dollar tracked sideways with each other over this time.

#4: The rise of China until the GFC

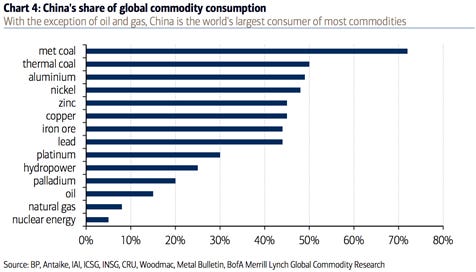

During this period of time China grew quickly, and consumed an incredible amount of resources. In respect of some metals, China was responsible for more than half of global consumption, as it simultaneously built infrastructure while expanding its industrial capacity and urbanising more rapidly than anywhere we’ve seen before or since.

In response to this, the US current account deficit grew rapidly and to historically high levels. The world needed US Dollars to buy commodities and grow credit to producers. The US obliged (with a whole heap of sub-prime mortgages to boot).

It is interesting that this run up in commodity prices over this 10 years from is still smaller than what happened between 1971 and 1980 during the period of the Great Inflation. In the ‘70s, commodity prices grew twice as much in roughly half the time. This says something about the supply side response by producers to the most populous nation in the world deciding it wanted to grow.

It also says a lot about how unique the ‘70s was.

#5: The GFC until the Ukraine invasion

The effects from the pop of the bubble in commodities and credit were painful and took years to work through the system. China growth targets fell as the credit amassed before the GFC took its toll.

The most recent cycle shows a particularly strong relationship, especially in 2009/10 and 2014/15.

#6?: The Ukraine invasion until….

There are plenty of reasons to think that we’ve turned a corner in commodity pricing and demand and as such are seeing the start of the next bull market in commodities.

The invasion of Ukraine and the economic sanctions imposed by the West on Russia has created a bifurcated market, separating Russian sourced oil from non-Russian sourced oil, Russian gas from non-Russian gas. This transition will take a long time.

The war and sanctions have had the effect of cutting off supplies of several key metals and chemicals, both from within Russia itself, and from Ukraine. Ukraine is also considered the “breadbasket” of Europe, supplying a large amount of wheat and corn and other foodstuffs. Whether the war ends sooner or later, it’s unlikely that sanctions will ease meaningfully anyhow, keeping pressure on commodity markets.

Global politics more generally is also having an effect on commodities. For the energy sector across the West, an underinvestment because of low prices and demand during COVID will hit the sector for years, along with “discouraged” investments due to ESG and climate concerns stifling output. You can throw any fossil fuel into this category.

Demand for all commodities is, however, overall strong, with the #1 commodity consumer, China, declaring through its GDP growth intentions for this year that it isn’t even considering a slowdown.

The biggest emerging market is the odd one out

Care must be taken about which currencies to short the US Dollar against. There is no real reason to expect the US Dollar won’t depreciate against all major currencies in a bullish commodity environment – the major currencies that are free floating of course.

After panicking the market in mid-2015 with a snap currency devaluation, the PBOC decided to start managing the Yuan against the US Dollar by adjusting it to a basket of currencies by the end of that year. Since this partial de-pegging, the Yuan has exhibited a positively correlated relationship with the US Dollar.

With weak commodities in the post-GFC era, how has the Yuan on average strengthened against the US Dollar? When you zoom in on the smaller commodity cycles in the last decade, why does the Yuan tend to weaken when commodities appreciate when it should strengthen like the Euro would?

The answer is that the direction of the Yuan and the direction of commodity prices are intertwined in a different way, because China’s growth policies produce both a weakening Yuan and stronger commodity prices. This is because:

China has a propensity to forcefully devalue its currency when it needs to prop up growth; and

China holds a place of global dominance in relation to commodity consumption and the use of commodities to prop up growth.

The Yuan is intentionally weakened to encourage growth. This will usually come with other growth measures that involve credit expansion, fixed asset investment and thus commodity consumption. The US Dollar, as a free-floating currency, doesn’t have the luxury of being managed against a broader national goal.

Interestingly, it’s the lack of an open capital account and free-floating ability that limits commodities being priced in Yuan, despite what those that scream death to the US Dollar will have you believe.

Causation and not correlation

The link between commodity prices and the US Dollar is not one of correlation, but causation. While commodity pricing is not widely accepted as the cause of movement in the US Dollar because of the misunderstanding of the role of Dollar pricing of commodities in the world’s monetary system, there remains significant evidence of this causal link.

This historical linkage will remain, and as such a sustained bull market in commodities will bring the next big Dollar bear market.

The timing of the bottom of the US Dollar may not be important when considering the long-term view. However, the absolute high in the US Dollar could be set at the time of the peak of the current Fed hiking episode, which will not be when the last interest rate hike is completed, but when US economic growth starts to turn downwards.

At that point, economies across the rest of the world will once again take the baton for growth, and the US Dollar will embark on its next cycle.

Trading Notes:

In this newsletter I’ve used the DXY Dollar index to illustrate trends. This index is heavily weighted towards the Euro (and prior to its inception, the individual member states). The Euro weight is around 57%, and China isn’t even included.

The Euro would be the top candidate to trade to express this view, followed by the Pound. The other option is to be long the currencies of countries that have most to gain from rising commodity prices, with the Australian Dollar, the Brazilian Real and the Indonesian Rupiah as good candidates.

Alternatively, buy USD/CNH to get to the heart of commodity demand.

For those that want to time the trade perfectly, waiting until hiking expectations reach a crescendo is the best bet. This is particularly important for pairs such as USD/JPY.

Be aware of what can be large swings within this trend. If not trading directly, this information can also be used to inform a general bias to other macro themes.

How does the new commodity bull market and weaker dollar fit into inflation/deflation discussion?

You argue the danger is deflation not inflation. And if not for the war I would agree in 100% - the US economy is structured so that any surplus from government spending eventually will go to the stockholders and higher earners, they tend to invest not spend.

But the war changes a lot. De-globalisation. Instead of just-in-time we will have just-in-time, new supply chains to be crated. US will reindustrialise, can’t afford to have everything manufactured in the rival state, China.

More military spending in general in the world. Net-zero. This requires a lot of spending, a lot of deficit spending by governments.