Why the short-end trends

Policy rates are made to trend by their human overseers – and this is great for returns

The Fed has heavily signalled that rate cuts are coming. This is meaningful – it will be the first non-crisis rate cut since the ‘90s. We will see if they will cement that change in direction in the next few meetings.

Over the last 25 years a change of direction to policy rates has meant a trend to rate changes that lasts years. This cutting cycle alone is priced to take 2 years to end. This trend creates a significant amount of momentum in rates markets.

Momentum is one of the most underrated investment factors in trading. While it’s normally associated with quant trading, I would argue that the best qualitative traders rely on momentum more than anything else.

A good trader they know when the tide has turned, and a trend becomes self-sustaining, understanding which analysis to consider when justifying that position.

Similarly, when that trend turns, they honour their stops and exit those positions. Trend following just systematises this.

Interest rate markets are one of the best markets to use this factor – and it’s because humans oversee the primary valuation tool of the entire yield curve.

The central bank’s policy rate

Setting the price of money is the primary job of the central bank in most economies. This is done by setting some form of interest rate (whether a benchmark rate or by utilising a repo rate that is set through central bank operations) for very short-term borrowing and lending. The term is usually for 1 week or less but is usually overnight.

The policy rate is set either by a board of governors or in some cases dominated by the decisions of one person. Since the ‘90s most central banks have had their policy rate guided by achieving some target related to inflation over the medium-term.

The driver of the decision making is not particularly important, as it could be anything. Ultimately a group of people decide on the price of money using some process that that might be deterministic to a certain extent (we want inflation at 2%!) but is almost always mostly qualitative (inflation is at 2%, but we are worried about it slipping higher or lower in the future).

The reliance on qualitative decision making is what gives a chart of a central bank’s policy rate the “shape” that is has.

This “shape” has consistently been an irregular wave, with both the amplitude and wavelength of this wave being massaged by the qualitative decision making of the boards of central banks.

The global wave of policy

Charting the base rate of all the major central banks shows a consistent pattern, and looking over the last 30 years, this global wave of policy looks extremely similar in each jurisdiction.

Policy rates have tended to fall since the inflation of the ‘70s, peaking somewhere in the ‘80s and falling ever since, with each subsequent peak in rates being lower than the last (until the latest cycle of course).

In addition, each country seems to share the same turning points, the same lower highs/lower lows, and the same consistent trend during hiking and cutting cycles.

There are a few exceptions to these observations, but in general they apply. For such highly correlated policy rates to be correct we can rely on two explanations:

Growth, growth expectations, inflation and inflation expectations must be far more correlated across countries despite their innate differences; or

The qualitative processes that each central bank employees have little to do with that specific country’s economic circumstances and prioritises “following the herd”, in effect saying the local circumstances don’t really matter.

The first explanation is more complicated than it looks. Over a long time scale, both growth and inflation are highly correlated across developed markets. They all tend to move in the same direction, and (until recently) it that has been down for both.

However, on a shorter time scale, they aren’t correlated, except around crises (especially financial crises).

Growth and inflation expectations are similar. On a shorter time scale a central bank will tend to forecast the same growth an inflation that only just prevailed, leading to similarly poor short-term correlations with other countries.

Once again it is the crisis that merges growth and inflation expectations and encourages co-ordinated rate cuts. These crises and their projected effect on economies is a qualitative decision which converge across borders.

So, when you put these effects together, we can explain the long-term decline in policy rates by the correlation of long-term growth and inflation, and the quick fall in policy rates due to the synchronisation of crises, and a synchronised recovery after based on converging qualitative forecasting. But what happens outside of these crisis events?

Unfortunately, there are very few events where rate cuts have occurred without there being some sort of crisis, usually recession fears with the addition of a financial system trigger.

The issue is that this is what we are facing right now. A consensus view amongst all central banks that inflation is over, and that cuts are appropriate because the risks to an upside breakout of inflation are limited.

Disinflation has not progressed uniformly, with some developed nations still printing well above their self-published targets. Yet the turning points in rates seems synchronised across the globe.

This would suggest that other factors are at hand, making their behaviour lean more towards the second explanation – that their evaluation of the data changes based on other factors, and is not consistent.

Hold on – how is this capitalist?

When you think about this phenomenon a little deeper, it does seem very odd that we have a committee of people, who are generally unelected, setting the price of money purely by diktat rather than some sort of market mechanism.

There is little in the way of checks over how they apply their qualitative processes, and while their behaviour is explained through minutes and press conferences and speeches and testimony in congress/parliament, there isn’t consistency or auditable historical decision making.

On the face of it this sounds like something that would happen in Soviet Russia, where the politburo would set the price of grain. Why does this exist when we set the price of money in the capitalist west?

The key difference is that the central bank who is setting the policy rate can produce an unlimited amount of the product they are setting the price of (money). The politburo doesn’t have that ability regarding grain, or anything else tangible. This changes the risk associated with settings prices by diktat, at least on the surface.

The ability to manufacture an unlimited amount of money in effect creates a “economic singularity” in the same way that the singularity in a black hole breaks physics.

The idea of money is so artificial that it doesn’t matter in which way you think about this problem it always leads to the same solution – there is no way for the market to be able to act rationally when there is an unlimited amount of a good on offer.

There, unfortunately, needs to be someone that oversees it. A person or a group of people that can decide when and at what price that unlimited support needs to be deployed.

Everyone has their ideas on how it should be done, and these things will always be supported by some qualitative reasoning based on how they think the economy works, with each of these opinions being entirely untestable via experimentation.

So, while it doesn’t seem right – it’s the best we’ve got (leave a comment if you would like a newsletter discussing these ideas).

No erratic and unpredictable moves

If you blame rising interest rates for the crisis that eventually causes them to come crashing down, then you would deduce that central banks will keep on hiking rates in a trending manner until something breaks.

Qualitative reasoning and mechanical forecasting of current economic conditions are the actual reasons behind this behaviour. A forecast will rarely show a significant change in economic conditions, with most forecasts being employed in a way in which they are used to explain current policy and used to justify it.

The forecast of economic expectations offers the means, the motive, and the alibi. It’s perfect.

It’s the equivalent of being a trader that just says every quarter that things are probably going to stay the same as they are, so I shouldn’t change any of my positions. Central banks are the equivalent of the momentum trader!

It’s for this reason that short-end rates trend just like a momentum trader would like them to, with varying degrees of effect depending on their proximity from the short-end of the yield curve.

Signalling a direction

This persistent trending nature of policy rates makes identifying turning points crucial for markets.

We’ve recently seen that happen. From the signalling and then confirmation that rate cuts were on their way, the Fed turned markets around, both in bonds and equities.

Communication and foreshadowing can only do so much, however. The Fed, setting up the market for rate cuts will need to deliver to guarantee that monumental shift in policy, the first that hasn’t occurred as the result of a crisis since the 1990s.

The Fed’s foreshadowing has seen nearly every other central bank shift their policy towards rate cuts, with some even pricing in the simultaneous or near simultaneous rate cuts.

Once they cement this change, it will set the trending path of rates until the next crisis. Cutting outside of a crisis will also mean another co-ordinated decision to signal a pause, or to pursue further hiking if they are wrong about their forecast for inflation.

There is an element of circularity in the market right now. If the Fed doesn’t pour the cement on the change in the direction of rates, then bonds and equity may reverse their recovery moves.

This pivot towards communicating cuts triggered a huge rally in the US 10-year note. On its own this left people searching for other answers for why such a large rally happened, but the explanation is nearly all in the re-pricing of Fed expectations over the next year.

The 10-year benchmark

From the November FOMC until year end, the US 10-year rallied 1.07%. Nearly the entirety of this rally can be explained by a re-pricing of 2024 expectations for short rates, rallying 0.82%, or adding a bit more than 3 cuts into the year.

In other words, the move in expectations for the path of the Fed Funds rate explained 77% of the move in the US 10-year note yield. The residual can be explained by any number of factors, including views on supply for new issuance or a reversal of short positioning affecting different parts of the curve in different ways.

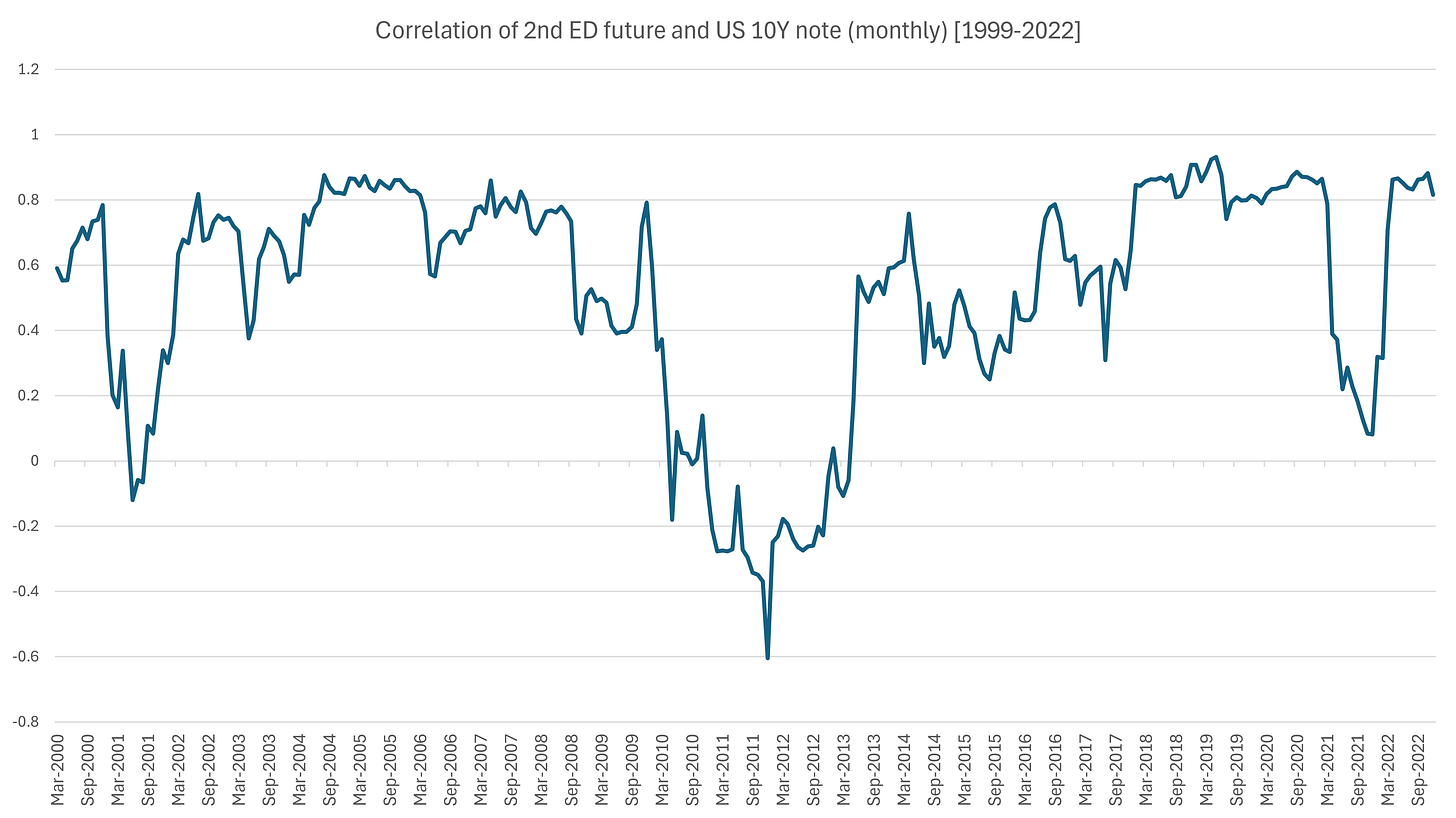

The relationship between short rates and the 10-year is fairly consistent throughout time. The correlation between the 2nd money market future and the US 10-year note is in the chart below.

Outside of periods of recession or when the Fed Funds rate was pinned at zero, correlations are solidly at around 0.80. The average over the entire period is 0.51, or excluding 2010-2013, 0.61.

The beta of short-end rates to long-end varies between 60% and 70% generally, making the 77% of the more recent moves quite unusual.

Despite the volume of market commentary that suggest that the drivers of the move in the 10-year needed to be explained by more than just the view on what the Fed is going to do, a factor of 77% for the relationship between long and short rates is far higher than what has persisted over the past.

This lower (and non-static) correlation dilutes the perfect trending nature of policy rates at the 10-year point of the curve. If we want something purer, we must get closer to the policy rate itself.

Momentum strategies in rates

The further you go out onto the yield curve, the lower the correlation with the policy rate is than the tenors below it. The 5-year is more correlated with the level of policy rates than the 10-year and so on, until you get to the shortest tradeable instruments being the first version of the money market future in that market, and then to futures that trade the policy rate itself.

The reason for this increasing correlation is that the final settlement of these instruments has less time to deviate from the effect of the level and movement of the policy rate.

Implementing this into a rates trading strategy requires more work than you may think. Something that is simple to test in equities or crypto is far more difficult in rates because of the shape of the yield curve and the inability to hold a perpetual instrument like an equity.

Either buying bills or bonds or futures over these instruments cause the same problem. The trend following process needs to roll securities as they get too far from their intended point on the curve, selling and buying the new security including transaction costs. The choice of security and the process makes trend following strategies harder to do than if you were trading buy and hold securities.

An equity will always have the exposure of that equity, as will a cryptocurrency. A bond will go from being a 2-year bond to an 18-month bond in 6 months – an entirely different security.

How well each maturity trends

The table below outlines the performance of key maturities on the US yield curve when some simple momentum strategies are applied to them. All performance includes transaction costs and over related slippage and are sized equally by duration risk.

Momentum is tested across 4 arbitrary moving average periods.

Across the US interest rate curve, our expectations are fulfilled, with short-end money market futures delivering the highest per annum returns, only starting to drop at the 8th contract (which represents the 3-month forward rate from 1 year and 9 months to 2 years in the future).

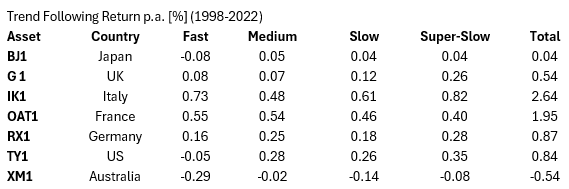

Below we replicate across different countries for front-end money market futures.

The US leads as the market with the best trends in short rates as it had both the GFC and early 2000s issues that the Fed had to adjust rates for. It also had the largest uplift in rates in the post-pandemic inflationary period.

For bond futures further out the curve, returns decrease as bond yields trade in a smaller range and more divorced from the perfectly trending central bank policy rate.

Finally, we can compare the 10-year point of the curve across different countries.

Per annum returns at the 10-year point of the curve are weaker than front-end returns, except for Italy and France which benefitted from credit-like widening against Germany during the Euro crisis, with this widening occurring in a solid trend which was able to be monetised.

What will stop short rates from trending?

None of this would likely be possible without the ultra-smooth trend in the level of policy rates as set by central bankers the world over. Their tendency to hike smoothly over many years and then cut aggressively in large >100bp moves guarantees continued performance of momentum strategies on short-end futures.

But what can change this?

The obvious answer is that there is a global change to the way monetary policy is conducted. This has happened before.

Most countries have targeted the level of the policy rate directly over the last 50 years. There have been periods of time however where the policy rate wasn’t targeted directly.

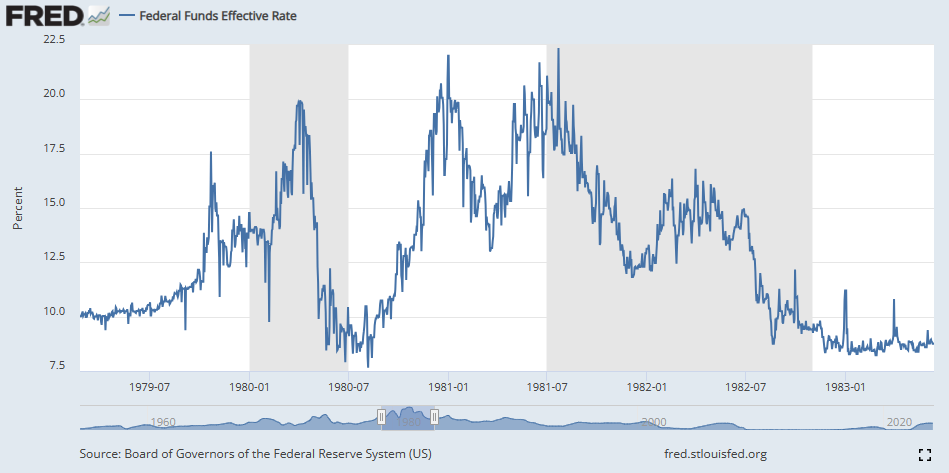

One that few know about was the during Volcker’s term in the ‘70s. Between 1979 and 1982 the Fed was targeting the supply of money rather than the policy rate, opting to apply a large range to the policy rate and letting the market set it to achieve their money supply goals. This is why you see so much volatility in the Fed Funds rate chart around this time.

They failed at controlling the money supply, something which we are probably thankful that happened.

The other time in history that would obviously bring an end to trend following as a beneficial strategy in rates trading is a period of static rates.

The currently accepted “ideology” around central banking is that a central bank should use all tools available to it (through the unlimited creation of reserves) to primarily ensure inflation is held at a desired rate, and with as little volatility as possible. Secondary to this is implicit support for economic growth and employment.

The opposite would be to set policy in line with underlying growth, which is driven by total factor productivity growth and population growth and leave it as it is.

This piece - one of my favourites - discusses the incentives in place that means that would never happen. Voters are just too addicted to forever growth in asset prices.

The next cycle

Trend following has been a fantastic trading strategy over the last few years. The huge move in rates, especially in the US, has been a gift to active managers.

The next cycle, potentially beginning in the next 6 months, may deliver something a little different.

A recession-less easing of rates won’t deliver the same strong momentum as cuts due to a financial crisis but will still work if the cutting cycle is extended and consistent.

Interesting stuff. I was actually just thinking the other day what correlation/quantifier/metric exists that shows lag/moves the long end makes when the short end is cut. This piece is just a “piece of the puzzle”. A very important piece however.

Peter - this is a fabulous piece. Thank you!