Charts & Notes: Problematic Private Credit

Core issues with retail investment in private credit can easily act as a contagion

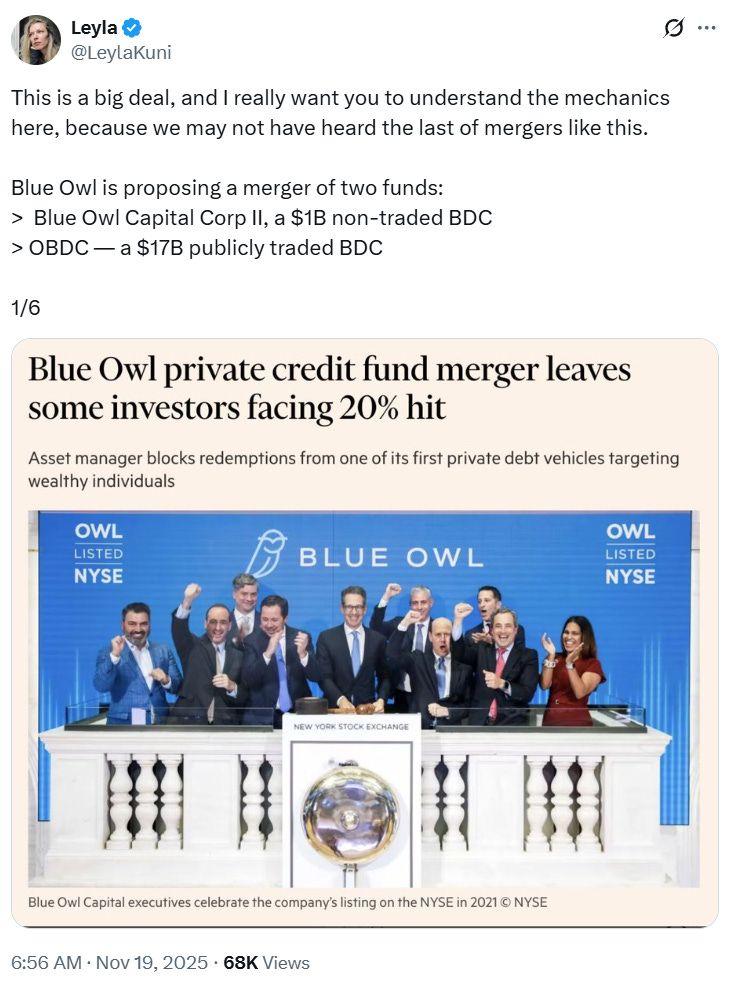

Private credit as an asset class once again grabbed headlines this week with a very sneaky merger proposal to relieve redemption risk on the non-traded fund, which allows investors to redeem at NAV (which seems very much like a free option to me which can possibly be sustainable).

While this proposal was later withdrawn, it is very important to talk about how it elevates financial contagion private credit presents.

Stress in this asset class can filter to revolt by investors very quickly. Exposures aside, I believe there are some core reasons why a revolt is inevitable.

The thread above goes through the initially proposed terms of the merger. In short, the non-traded fund will merge with a traded fund, where redemption liquidity is provided by trading shares.

The kicker is that the traded fund is trading at a much more realistic 20% discount to NAV, resulting in the investors in the non-traded fund losing their “sell at NAV” put and taking an immediate hit of 20%.

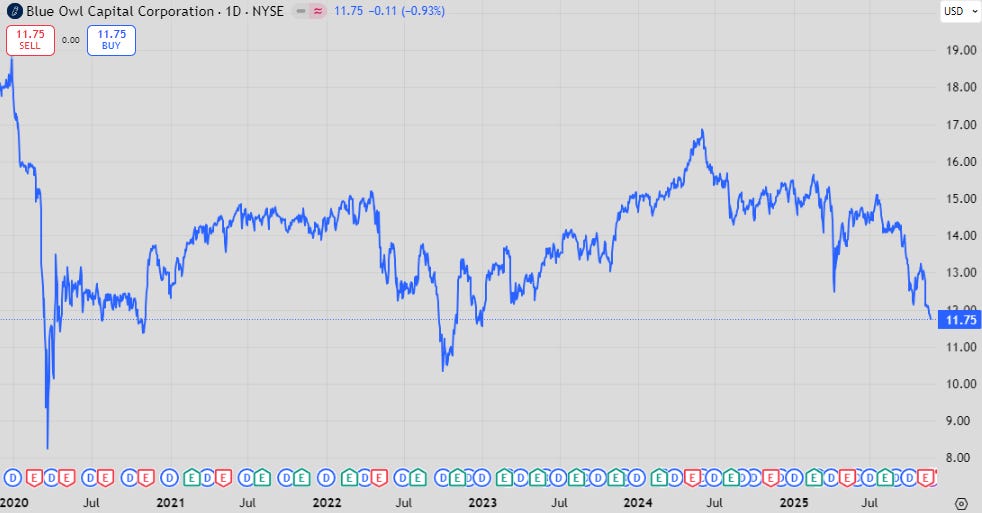

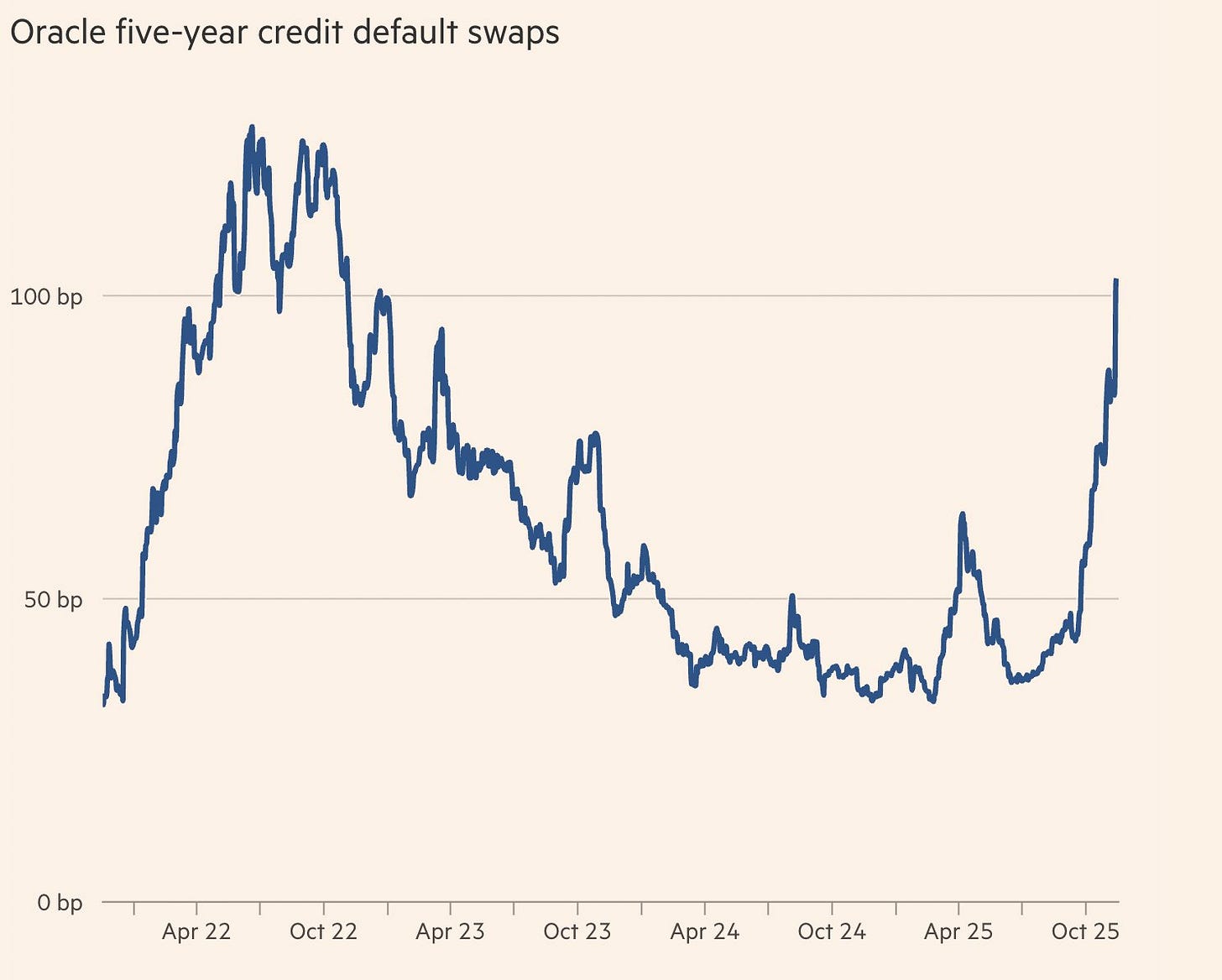

For this particular investment, it seems to be the underlying exposures which have caused some concern recently.

Oracle and Coreweave CDS have widened recently within a similar theme. Oracle (above) hasn’t seen a material widening in my opinion - moving from 50bp to 100bp isn’t a crisis but just reflective of the size of the capital expenditure they’ve committed to. This commitment should cause pricing to correct.

Offering the free option to redeem at NAV is ridiculous in its own right as it’s obviously unsustainable, but this points to why the growth in the sector is a danger to itself.

Blue Owl (wisely) withdrew the proposal after blow-back. This doesn’t change the underlying dynamics. It also leaves the question of what they will do now. If redemption requests were too large in the first place to encourage such an idea (and surely they will only get worse now), they will either have to borrow to fund redemptions or gate the fund. Selling assets will be unlikely as it won’t reconcile with allowing redemptions at NAV.

Allow a revalue to drop NAV and their redemption problem will just increase. The core of the private credit problem.

The core problems with private credit

I believe that Private credit offers unique exposure to the right investor. It isn’t inherently bad in itself, it’s just that it’s illiquidity encourages poor behaviour and incentives from most managers, while simultaneously playing on the uninformed desire for investors to own an asset with what appears to have no volatility.

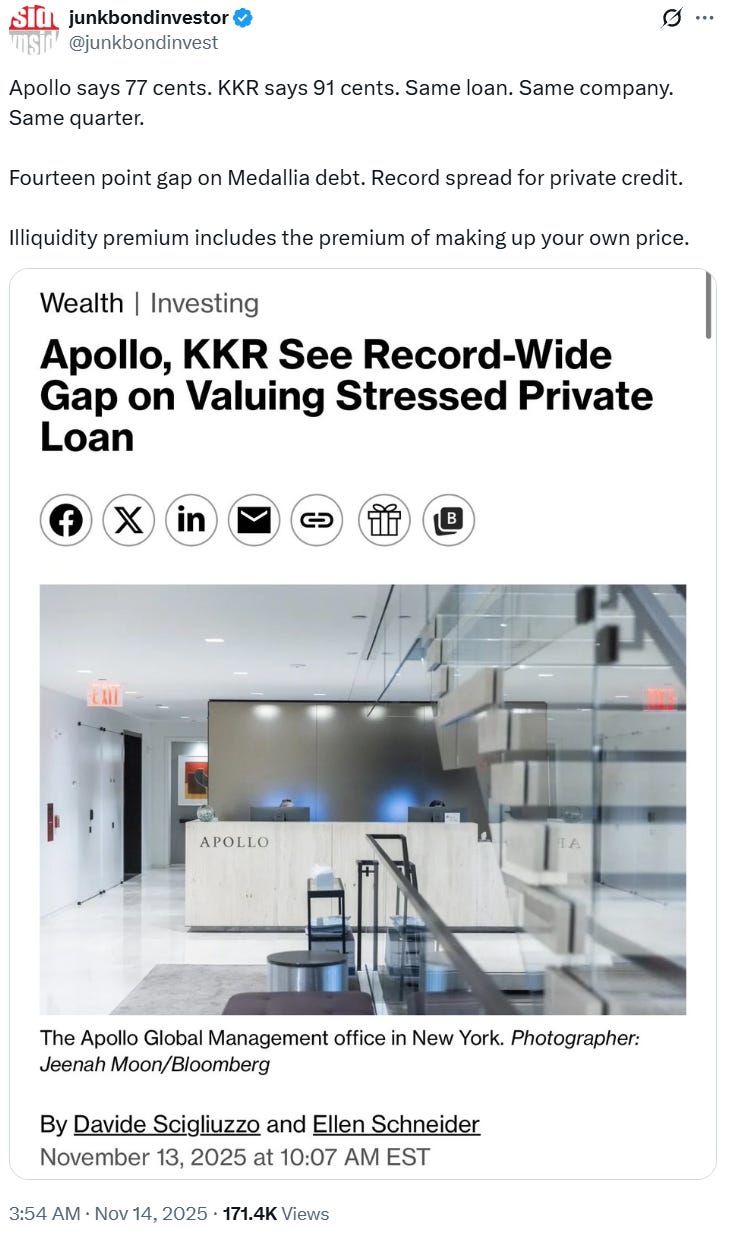

Most of the time private credit will exhibit almost no volatility. This is exacerbated by the behaviour of managers when producing valuations for holdings in their funds. Without any traded markets, they are incentivised to never deviate their marks from par unless there is a very serious chance of non-payment.

This leads us to issue #1:

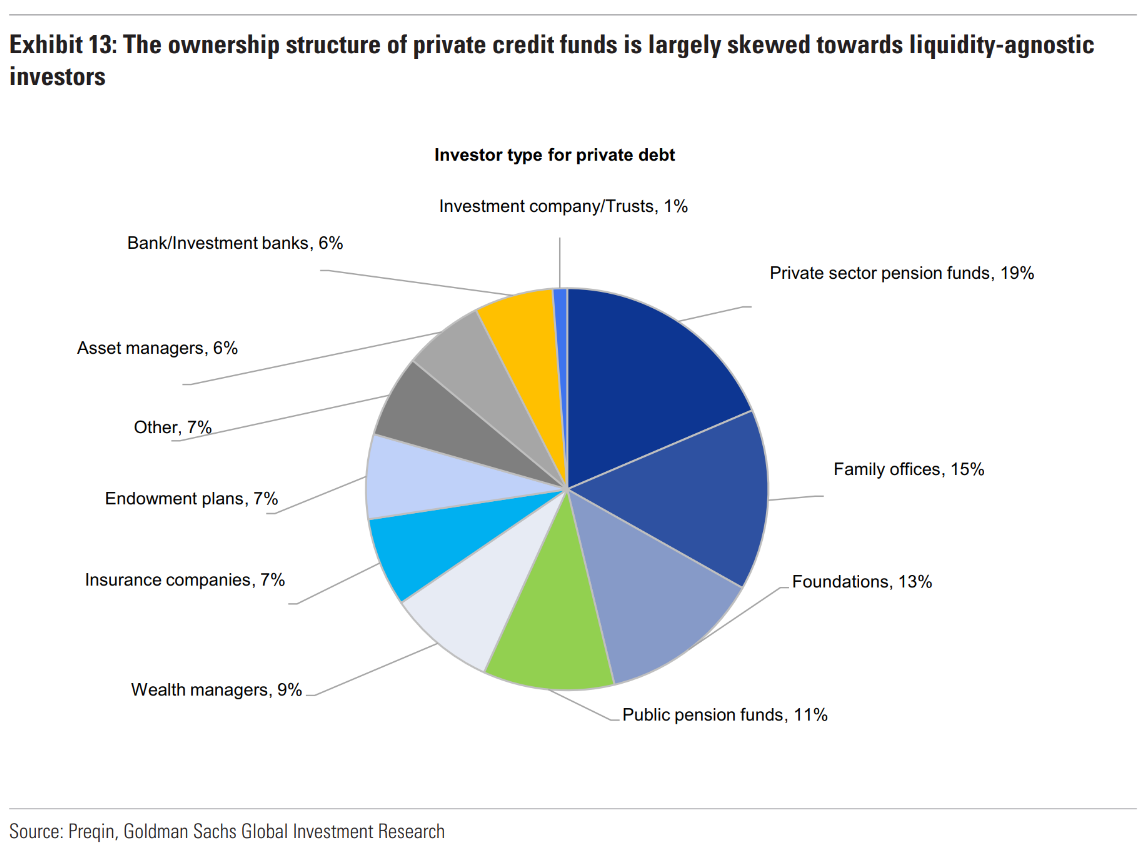

Investors (especially retail) do very poorly with investments that experience an extremely sharp change in volatility.

If they are used to an investment that only increases by the accrual they receive, a sudden 5 or 10% drawdown will have an outsized effect on their interest in the investment, where an investment that is highly volatile investment will be more likely to avoid redemptions even with a much larger drawdown.

It’s really all about expectation. They have been trained to expect little to no volatility, so any change will cause a revolt.

This is rarely limited to the funds that actually have an underlying issue with their holdings. The GFC is littered with examples of credit funds that returned all of investor’s capital many years after they were gated for redemptions.

We can be sure that there are many investors that are susceptible to this because public credit funds have been around forever and haven’t experienced anywhere near the same increase in size. More diversification was a convenient explanation, but the real underlying reason is the volatility history for private versus public credit funds.

This profile isn’t bad for investors that understand it and can live with drawdowns when they occur. For this type of investor private credit makes a lot of sense as it offers far more diversification than public markets, and exposure to industries through specific funds that wouldn’t have been able to be obtained otherwise.

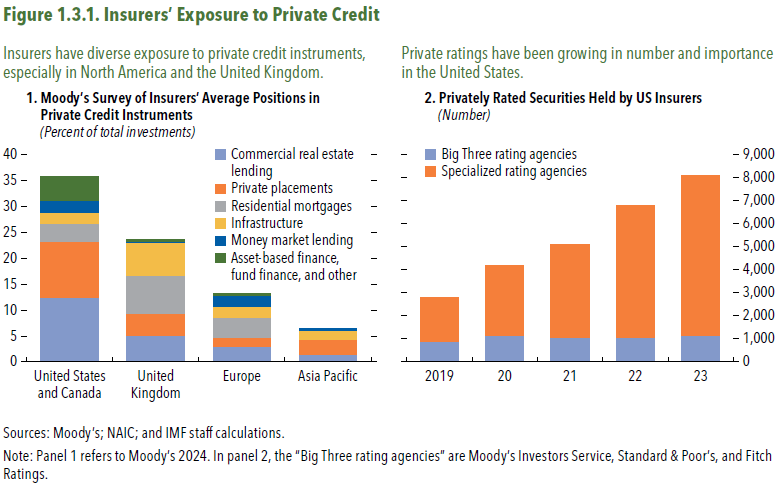

Insurers are an example of this. Insurers tend to invest their “float” (premiums paid but that have been unearned) in fixed income instruments. Private credit is a better way to obtain this exposure, as an insurer would generally hold to maturity anyhow.

The lack of volatility is also partially irrelevant to these institutions who might have an accounting classification would’ve resulted in valuations being kept at par anyway if they held them directly.

It really depends on the type of investor and their expectations on whether having a volatility smoothed outcome is good or not.

Moving on.

Issues #2 and #3 surround credit quality and their interlinked incentives regarding fund raising for private credit funds.

Issue #2: Private credit managers have yet to show that they are better lenders than the banks.

Are private credit fund managers better or worse at choosing credits (whether they be by name or industry) than banks are? Nobody really knows.

Initially the bumper liquidity premium available on private credit lending delivered better outcomes for private credit funds even with the same relative losses. This premium has eroded with the growing size of funds under management, but to be fair this is very difficult to measure this precisely.

Direct lending portfolios seem to have very low arrears rates at the moment, but so do the banks.

If they aren’t any better than the banks, can we expect the same 10-year cycle in bad lending? This cycle generally isn’t deadly for the banks (even though sometimes it can be) but combined with issue #1 they can be for private credit.

Issue #3 covers incentives for lending:

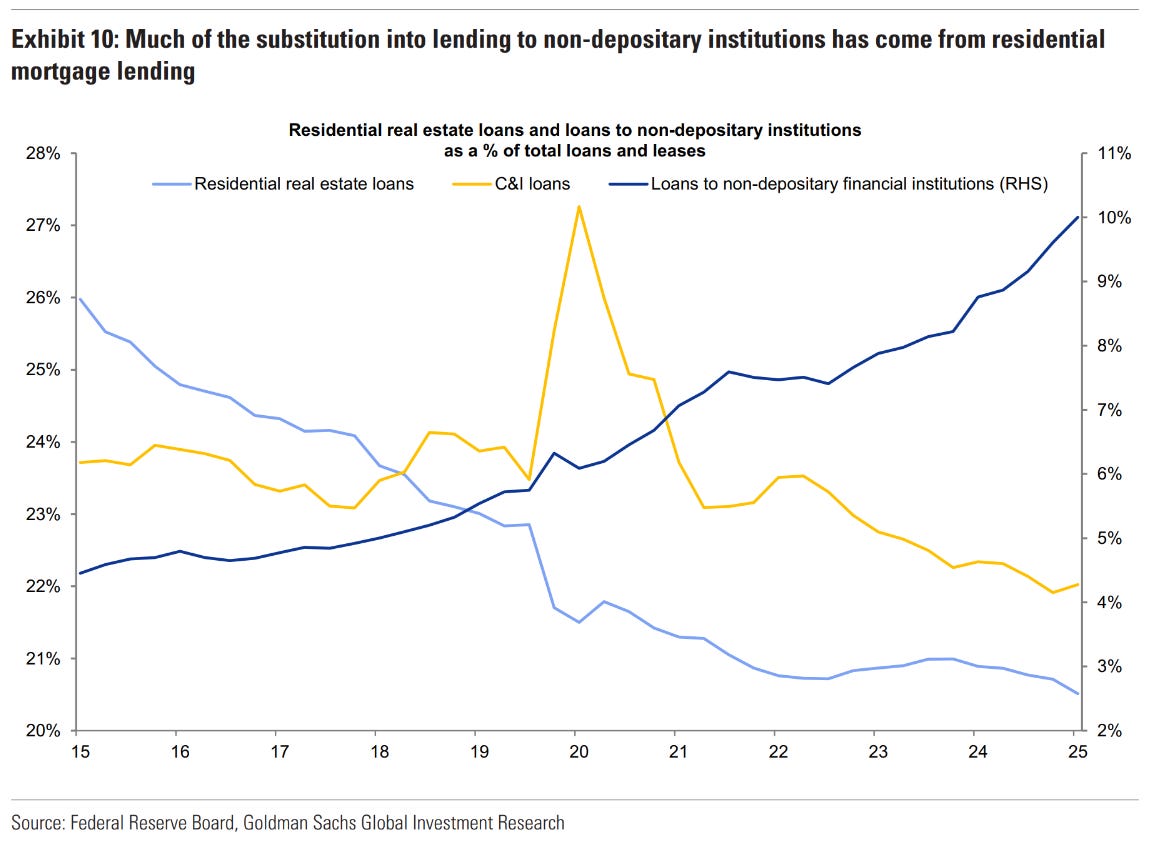

Issue #3: Bank lending is driven by demand for loans; private credit lending is driven by demand for private credit as an investment.

This last core problem is the tinder for the other two issues to come into focus.

The underlying reason for the GFC was that banks were aggressively expanding into low-quality real estate lending because of:

Profit competition between banks

The regulatory capital arbitrage for the rating on this lending

Bank wholesale borrowing to fund this being practically unlimited

Adjustment of capital requirements has broadly fixed all of these problems to the point where banks are now driven primarily by demand for credit rather than trying to create their own supply of it.

Private credit has different drivers here. If applications are coming into your funds, you have to find someone to lend to otherwise the dilution will diminish returns for other investors. This is dangerous.

Add to this the presence of performance fees, which align itself with the 1st GFC problem. You need to lend riskier to drive returns and earn performance fees, just like the banks did in 2005 and 2006.

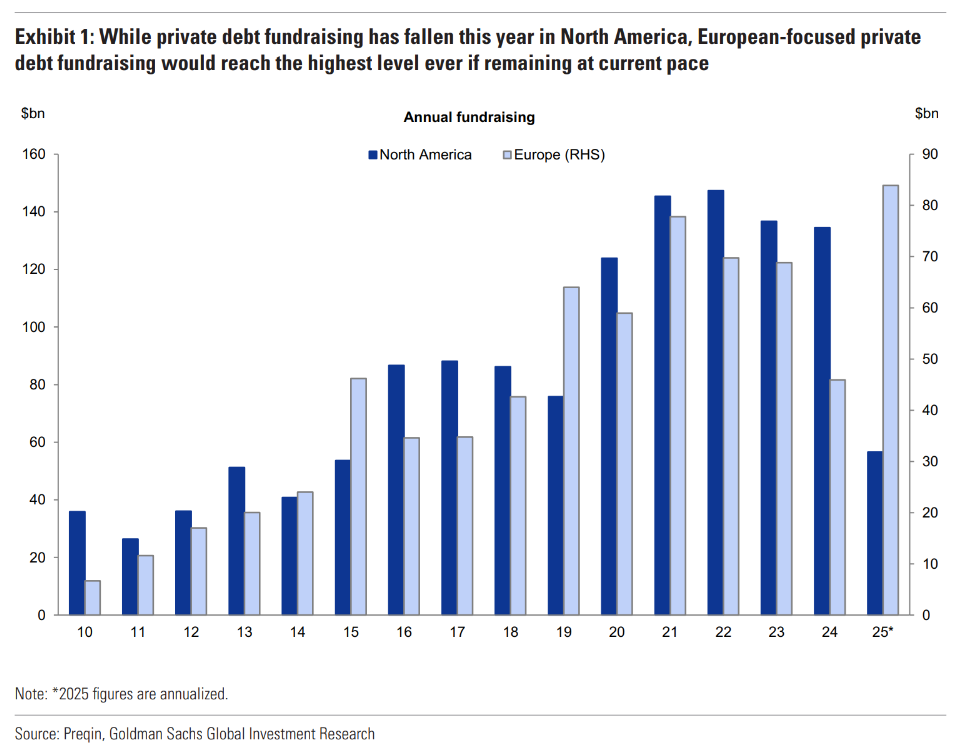

The private credit sector has grown immensely, and with that comes the risk of poorer lending as all inflows have to be invested.

The most dangerous known-unknown

I’m not revealing anything new here about private credit, as many share the same concerns.

When it comes to financial crises it is very rare that lightning strikes twice in the same place.

There is always a new innovation, a new market or a new type of security that goes under the radar and doesn’t get properly regulated until that crisis happens.

Bad lending, financial crises and deep recessions

Note: I wrote this newsletter before Silicon Valley Bank et al. failed, but have added a note about it at the end. As this Twitter thread highlights, I do not consider this failure one that is systemic and isn’t part of this analysis. I am sure you’ve all had enough of SVB already anyway.

Financial crisis and contagion is one of my favourite topics. Please see one of my older posts above to understand how they start, what path they take to spread, and how they can be self-sustaining.

You might need it as the private credit sector tries anything it can to avoid the dreaded “gating”.

Exceptional breakdown of the core pathologies. The 'redemption at NAV' put option is indeed a ticking time bomb, but the most dangerous transmission channel is Issue #3: investment demand driving lending supply. This inverts the credit cycle for mid-market businesses. When the fund inflows slow or reverse, credit availability for otherwise viable companies doesn't gently tighten -it slams shut, as the fund's incentive is to gate, not to patiently steward.

We analyze these transmission channels between institutional capital flows and business liquidity at Trade Credit & Liquidity Management (TCLM). https://tradecredit.substack.com/