Charts & Notes: How to turn a European bear into a bull

Oddly, the bear might be arguing the bull case for European stocks

Charts & Notes will move to ad-hoc releases in December and the holiday period and come back weekly in January. In the meantime, I’ll finish working on a much overdue new long-form piece entitled “How Western Governments Go Bust”. I’ve really enjoyed writing these and have appreciated the engagement and since starting the weekly!

The German DAX had an incredible run from the US election last year up until the end of Q1, registering gains of nearly 20%. Trump meant a push back on European defence spending, and domestic political pressures combined with a lagging economy finally put German fiscal spending on the table.

Since then, little has happened. The DAX has traded in a tight 5% range since the Liberation Day recovery in markets. The Eurostoxx has fared better with a bigger tech exposure.

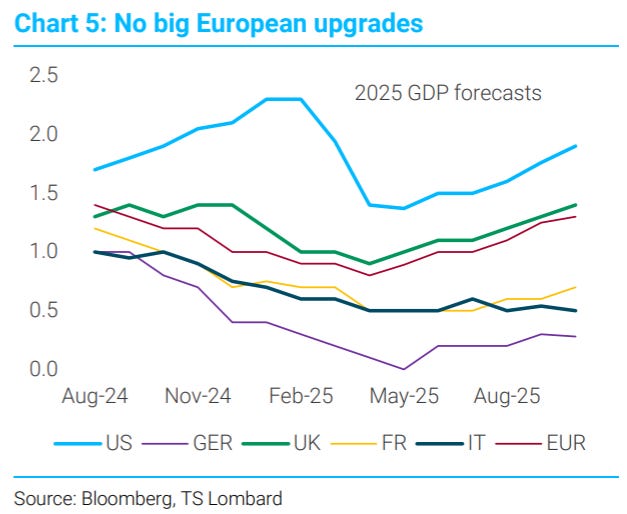

Asset allocators jumped on the narrative and tilted their portfolios towards Europe over the US. For those that got in late, the switch hasn’t treated them well.

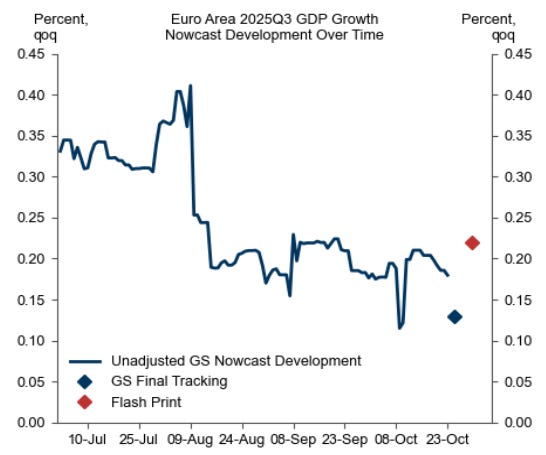

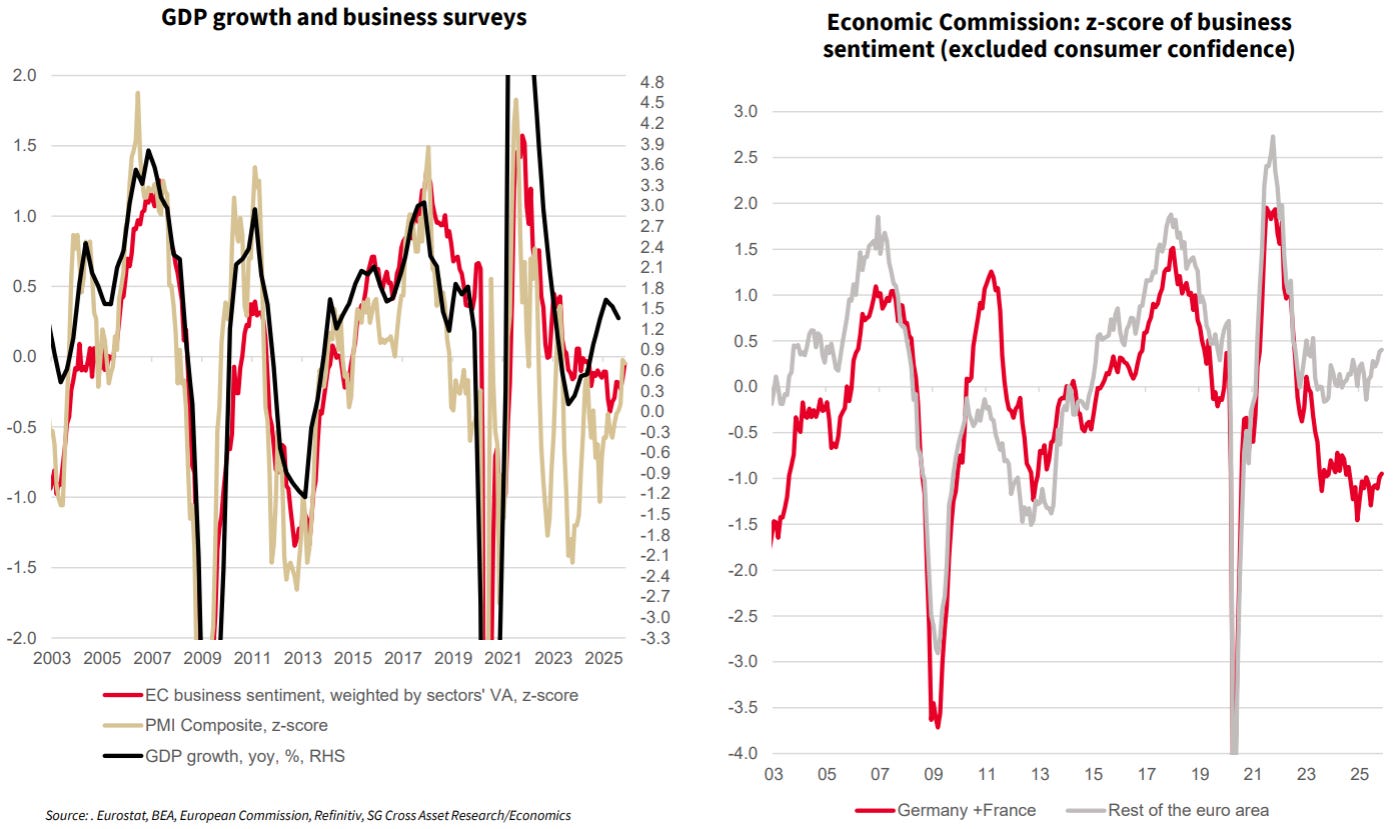

Recent GDP data has the Euro Area growing at 0.2% QoQ, with Germany basically posting (once again) zero growth.

The breakdown doesn’t deliver any good news, with exports and consumption dragging. Inventories are climbing. Bulls will say this is historical data that doesn’t point to where the economy is going.

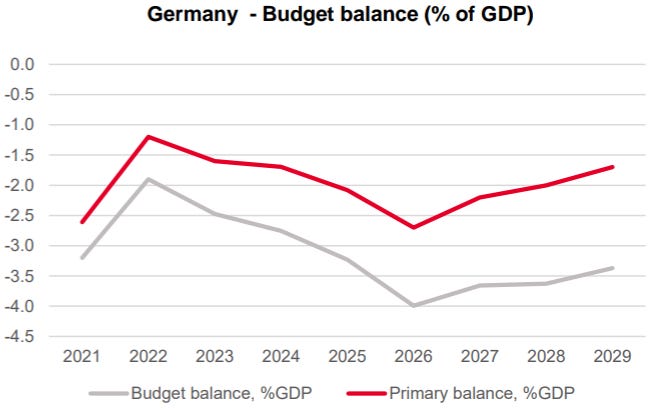

Q1 should see German stimulus starting to be deployed. The market has done its thing and priced this equity market friendly stimulus, but the slow delivery has many asking questions, and those that are doubtful have had the hard data backing them up.

Views fall into 2 camps:

Bearish: China has weakened the German export machine too much for the fiscal impulse to overcome.

Bullish: The slow delivery has tempered expectations, and Europe will over deliver in 2026, while exports will bottom.

Let’s have a look at both.

The bear case

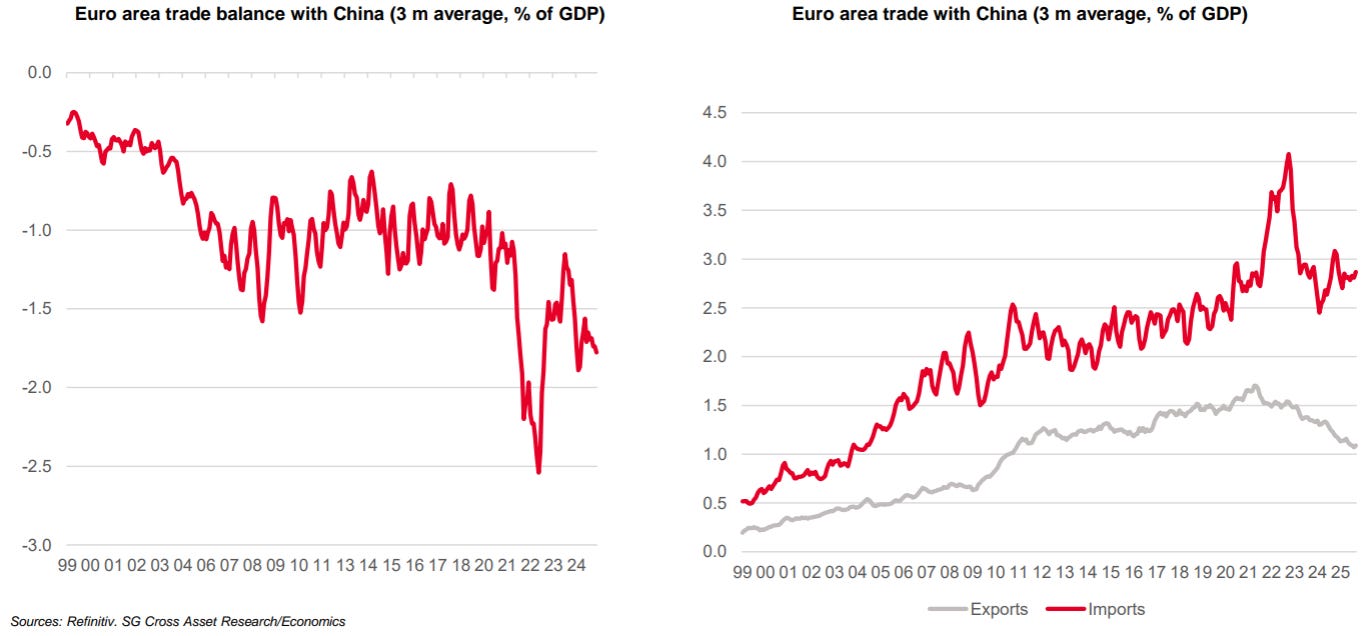

The core of this argument is that the Chinese external balance is only going to increase with the push to grow exports.

This has a large effect on Germany (from Goldmans)…

…with rising Chinese imports into Europe not being met with trade in the other direction.

The chart on the right above shows how dire this has been, with European volume share shifting entirely to Chinese exporters.

Germany was a winner in the rise of China. For much of the last 20 years, the Chinese relied on high value-add intermediate manufactured exports from Germany to enable their industrial machine. You couldn’t make a factory without German parts. This helped Japan as well.

Now Germany runs a deficit with China, and it seems to be getting worse.

The currency continues to be an issue as well. With the ECB either done or with only 1 more cut to come, respite from a better exchange rate is unlikely.

Goldmans estimate that a rising Chinese trade surplus with Europe will further slow growth by 0.6% over the next 3 years. If the core thesis stays intact, this is a significant headwind.

This has seen Germany struggle. While very mild, German GDP is still below the 2022 peak.

Part of this issue has been productivity, something which has affected many western countries. This is all while labour availability has been low (which has driven a low unemployment rate).

Low unemployment is a European mirage

Mario Draghi’s report on European competitiveness won’t contain anything of substance for those who are students of the European economy. It could have been written 10 years ago, with the only meaningful changes being the lamenting over Europe’s lack of leadership in 3D printing rather than AI, like the report suggests.

The nature of the planned fiscal stimulus (defence and infrastructure) is great for stocks, and it’s important to divide the two here (I’ll get to this later).

For GDP, is German stimulus enough when nearly all of the rest of the EU is tightening policy?

The more bullish banks have German growth at above 1% next year, from effectively zero this year. The bears don’t think this will eventuate, and even if it does, they think it won’t be enough to lift all boats.

The bull case

Expectations are where the bull case is strongest.

Expectations are already very low. The easy side to take is the bear case because the trends have been so strong.

Seeing how this quarter’s GDP print has evolved over time is enough. Dire.

On the other hand, the periphery is still doing well. Spain is the standout after finally ditching the ball and chain of post-GFC deleveraging. Even France surprised much to the upside this quarter on exports and business investment, delivering 0.5% QoQ in the middle of the disruptive political situation.

PMIs are heading in the right direction, as is business confidence.

This has been seen in business investment and housing activity as well.

Even recent German auto demand shows that trends can reverse.

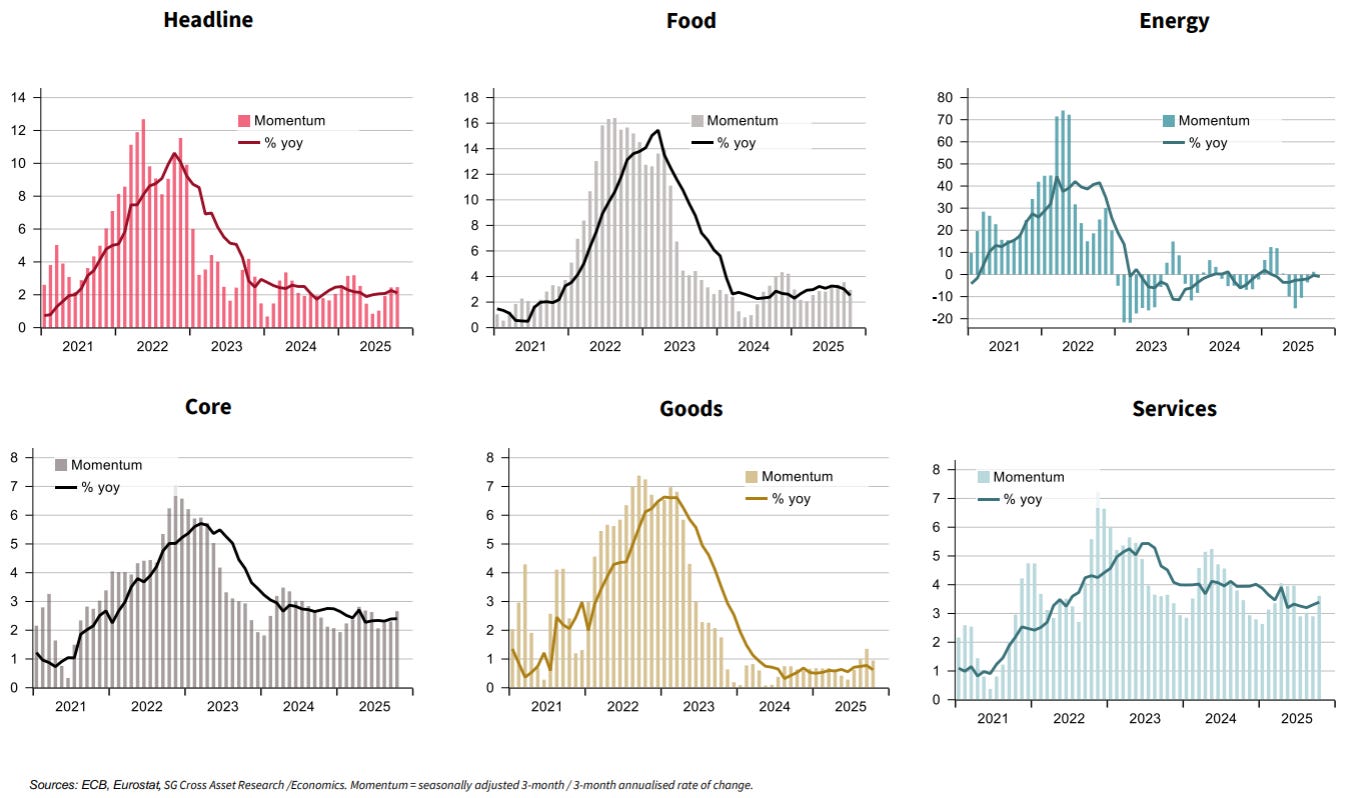

Consumption is also looking up. Wage growth combined with (ironically) the falling price of imports act as tailwinds.

This is reflected in goods inflation above. Inflation in Europe has been at target for a while now and unlike most other countries, is looking weaker. This might allow the ECB to come into the picture again, especially if the immediate effect of German fiscal stimulus is below ECB expectations.

You can’t trade GDP

The bear case might be missing the point a little. Even if it is correct and the trends which have put stress on the German export machine continue, there are other things that might matter more.

You can’t trade GDP. Even if they are right and German GDP growth ends up below 0.5% for 2026, fiscal stimulus is directed right at the companies that make up European indexes, and the trade is in equities, not in broader economic growth.

Declining capacity utilisation might work for higher equities. German companies such as Continental and Volkswagen are redirecting labour and factory capacity to companies such as Rheinmetall. Directing fiscal into supply constraints is usually the worst outcome - declining export demand could actually help the efficacy of the fiscal effort.

Continued Chinese export dominance might force the ECB’s hand. There is evidence that rate cuts are starting to help with consumption and credit starting to grow again. Slowing inflation would cause the ECB to deliver more, with benefits extending to the currency as well.

Low expectations have put the German fiscal narrative on the backburner. If a mean reversion happens, the upside is likely bigger than the downside.

Thank you, Mr. Farac.

Great dive on Europe and it's problems.

Best,

Valentino