Are we even capitalist?

We've drifted as a society, and anger for this on both sides of the aisle is misunderstood

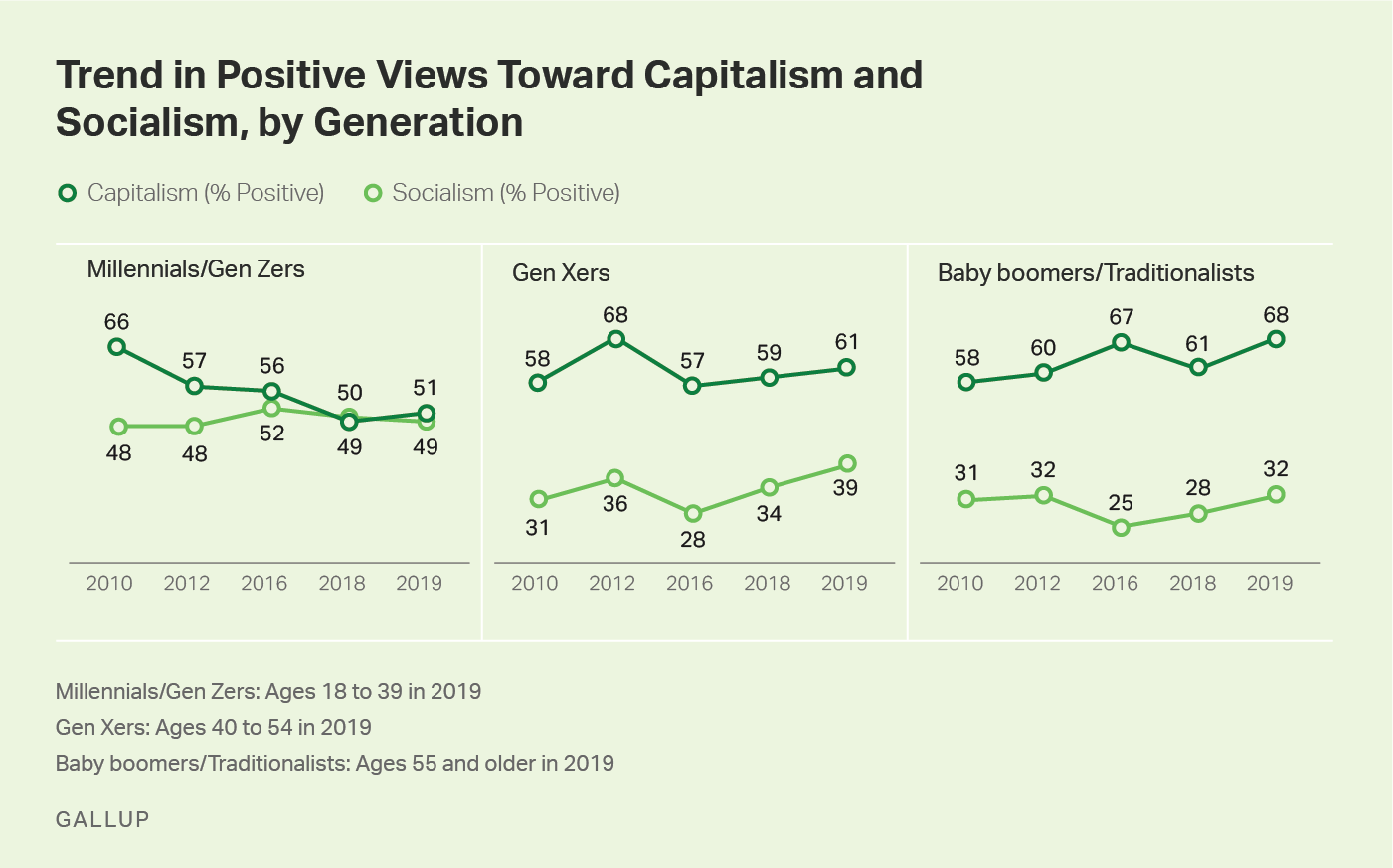

Anti-capitalistic and anti-government sentiment has been rising rapidly since the Financial Crisis. Political division, also rising rapidly, seems to be less about policy or value arguments but is more related to intensifying views on the very core ideologies western democracy is built on.

Movements like Antifa, BLM, January 6 and the Tea Party have become part of the mainstream. These movements at their core are highlighting a perceived injustice and are actively trying to correct it by pushing an agenda to purposely change the role of government in determining outcomes one way or the other.

Those looking to reduce the role of government see government being stronger than ever, especially after COVID related restrictions. Those that call for more government see it as the only solution to rising inequality and social injustice. Individualism versus collectivism. Decentralised versus centralised. Libertarian versus authoritarian. Capitalism versus socialism.

These ideas go to the root of an individual’s sense of freedom, and as such encourage a visceral response, so it makes sense that each side is becoming more entrenched and fighting harder.

I argue that the economy has drifted away from being a free market, and this has been the driving reason for this increase in tension. This has happened because of combination of factors – the government has become a larger part of the economy while other parts of the economy have become monopolistic. Ultimately, the market has become less free, and as a result has possibly become less fair as well.

The drift away from a system that has historically made people happy and prosperous has happened in two directions, both towards communism and simultaneously towards a more extreme version of capitalism.

Centralised vs decentralised

If you believe that capitalism isn’t the best way to organise an economy, then you believe that economies should be centrally controlled. Centrally controlled economies rely on individuals to set prices, allocate capital, and determine supply and production for all the products in the economy rather than the economy as a collective.

Giving individuals this responsibility may seem appealing but is doomed to failure. To highlight the difficulties with this, consider a popular product like “Remote Control Poo (Sparkly)”.

In a centrally controlled economy, there is somebody that has the right answer for the following questions:

1. Should we deploy resources and capital to producing “Remote Control Poo (Sparkly)”?;

2. If so, what features should “Remote Control Poo (Sparkly)” have (should it drive forwards, backwards AND spin?);

3. How many “Remote Control Poo (Sparkly)” products should we produce to satisfy demand?; and

4. At what price should we sell “Remote Control Poo (Sparkly)” that delivers the best outcome for everyone in the economy?

The idea that there could be a person or committee that can determine the right answer to these questions so that the economy obtains all the utility it can from this product, while achieving an equitable and fair outcome for all, to me, seems impossible. While the absence of a product of this nature wouldn’t affect society meaningfully, its existence in our capitalist-like economy means that someone appreciates it and derives utility from it (no judgement from the author), and someone is making profit from it.

This absurdity of this is example is one of the best ways to show how a centrally controlled economy would achieve sub-optimal outcomes, purely due to the infinite number of decisions and infinite amount of knowledge needed to deliver all the products and services that there might be demand for. These decisions exist at every point of the supply chain, and any mistakes compound and multiply as you move closer to the final product.

When you move towards the provision of food or other vital services, these errors in capital allocation and price and volume setting become much more serious. Either prices are set too low, and losses must be funded from other parts of the economy, or prices are too high, and a large proportion of people end up without any food at all. This endgame has affected every nation that’s attempted communism in the past. The USSR had bread lines towards the end of its existence, and more recently Venezuela has experienced the same issues.

Ultimately in a purely communist society, even with the purest intentions and zero corruption, deciding on all these things by committee is impossible. The first few years of communism would be pretty good, but mistakes will inevitably be made, and soon enough the economy will, at best, operate at a low efficiency and, at worst, result in starvation and death.

This isn’t to say a purely capitalist society would be any better. Initially capitalism would be able to achieve the greatest breadth of products in the most efficient manner as individuals would optimise for profit and therefore efficiency. Any niches would be exploited, resulting in the best possible outcome for both producers and consumers.

However, without anybody enforcing any minimum rights or any other ethical standards, those that amass the most capital will be able to out-compete anyone else without any accountability. Profits turn from being an incentive to produce a better product, to rents extracted from monopolistic positions. Workers can be exploited, and the environment trashed. The incentive to achieve any level of efficiency in production becomes lost because there is no competition to enhance efficiency, so eventually the same issues that destroy a communist society will destroy a purely capitalist society. The people will rebel and lead a revolution that dismantles the structures of power.

I’ve considered the extremes of both ideologies to illustrate the point that there is no “perfect” system, and, like most things, the best outcomes are found in a compromise between the two. Both communism and capitalism have faults that arise from different issues, but that ultimately lead to the same outcome.

A continuum of ideologies

When someone says they are a capitalist, they are unlikely to mean the extreme version as described above. What they really mean is capitalism with socialist characteristics, with the socialist part adjusted for the extent of that person’s sense of moral obligation to members of society who are less well off. This leaves room for the role of government in society.

The same goes for card-carrying “communists”. These people might cling to the utopian idea that someone in charge will remove all the injustices of modern life creating an equal society, but they also wouldn’t give up their own Apple iPhone if asked to achieve equality. Utopian idealism is more common with younger people, hence the popularity of socialism in universities. However, when the same students are asked if they would distribute their exam marks to those who didn’t perform as well, their attitude towards success based on personal merit typically changes somewhat. Contemporary “communists” usually want a version of communism with capitalistic elements.

The only people that support the extremes have a vested interest in them. The incredibly wealthy would prefer a strict capitalist society as it would allow them to accumulate more wealth, faster. You may think that the poor would be cheering for communism but that isn’t true – it is the bureaucracy that have the most to gain, as they will be the people allocating the capital and making all the decisions.

A poor person is equally as disadvantaged in capitalism and communism. Where the fight really occurs is between the politician or bureaucrat and the wealthy businessperson or company. The bureaucrat is powerless in a strictly capitalist society, and the wealthy person loses all they have in a communist society.

For this reason, democracy has never been able exist in either extreme. A politician that has successfully converted an economy to communism would never give up the power. In extreme capitalism the only vote is through each dollar you hold, so your rights as a person don’t really exist. This would be a hellish existence.

Working out what ‘capitalism’ is

Most of the developed world operates somewhere on the continuum between communism and capitalism. When people speak of where individual countries reside on this continuum , they would normally put China at one end, then the Scandinavian countries, then Western Europe and finally the US at the other extreme.

The main reason most agree with this categorisation is due to the perceived amount of social support the government provides in each of these countries. Scandinavian countries provide state-run free universal healthcare, free schooling etc, where the US has less of this.

The comparison based on social support falls flat when considering China, which has very little in terms of a social safety net available to the populace. This isn’t very communist, even though China’s ruling party has the word “Communist” in its name. The Chinese banking system is almost entirely owned or controlled by the state, however, which would suggest it is more controlled than our other comparison countries.

I would argue that socialising services is not necessarily contradictory to capitalism. In the case of schooling, for example, having the government as the main buyer of schooling services and offering these social programs in a universal way, may result in a better outcome for children, while deploying capital in the most efficient fashion.

In this sense it is useful to think about government as a corporation that has achieved monopoly status in this sector. Elon Musk said the same recently, and on this point, I agree with him. Schooling, even though it is administered by the state, may be the best, or close to the best, way of providing this service. Private schools can’t seem to beat the public system on a per-dollar basis in most countries, so maybe state-run schooling is the path that balances needs and efficiency.

Somewhat contradictorily, the staunchest commentators on the right in the US will argue strongly to keep the current medical insurance system, because the alternative that those other “socialist” countries have of state-run medical care represents a shift to “communism”, and for this reason Medicare-for-All remains politically untenable in the US.

How US health care confuses the continuum

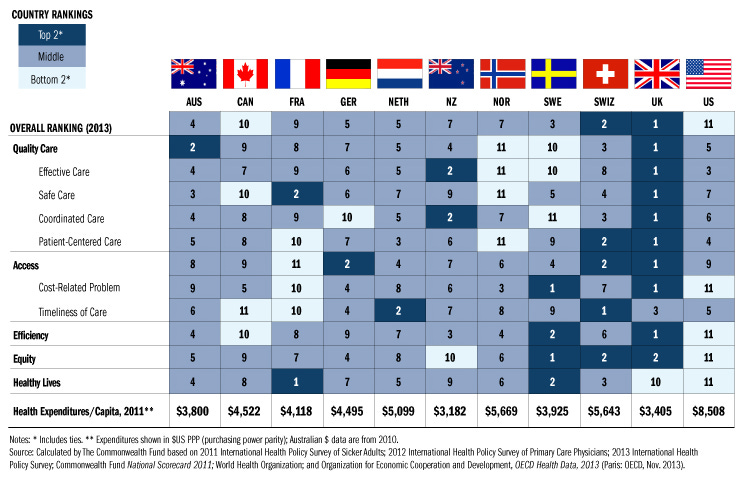

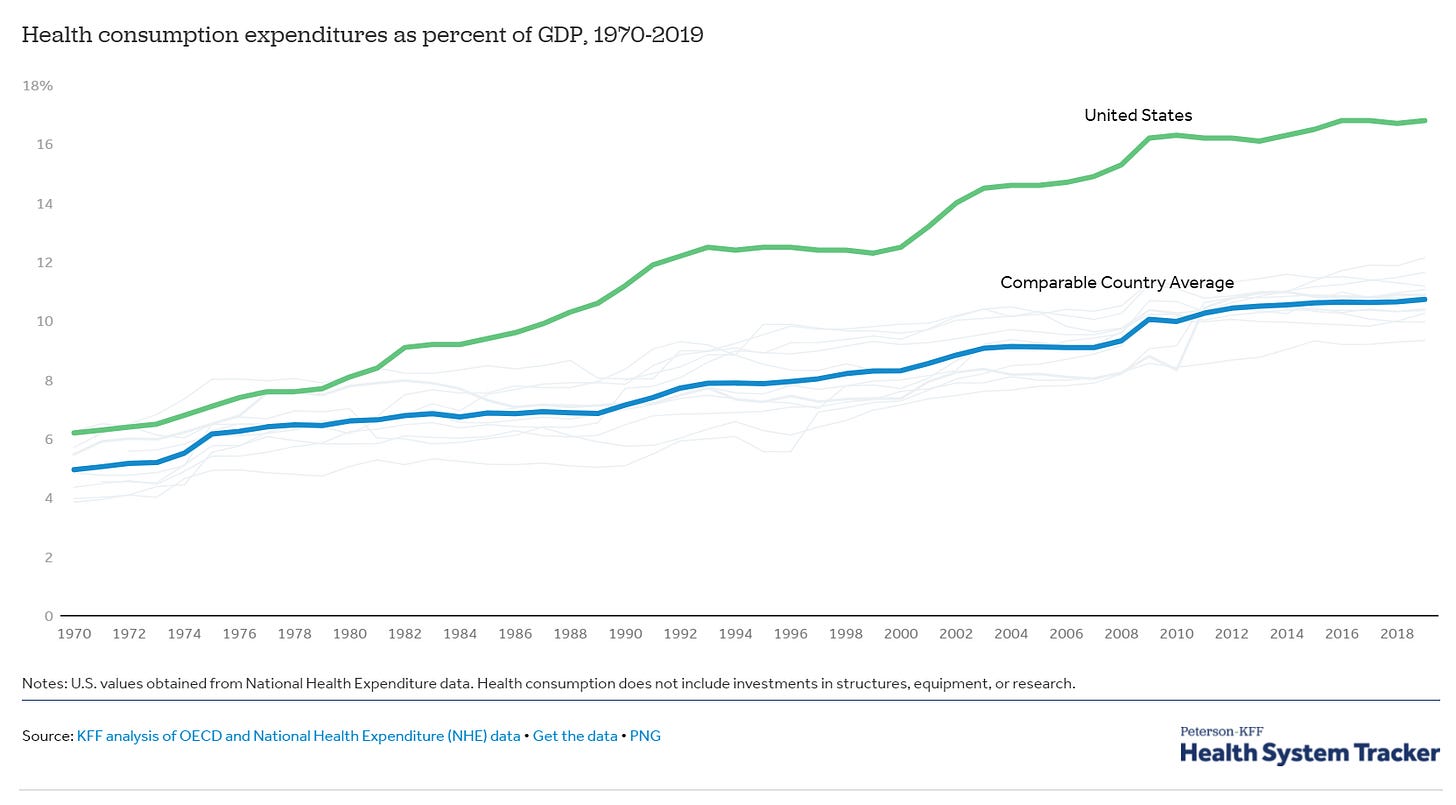

The US health care system is inefficient, while simultaneously being far and away the most expensive in the developed world. Health outcomes, in general, are also worse in comparison. This isn’t news to most people.

At the heart of why the system has such poor cost outcomes is the exact same problem that plagues every communist economy in the final stages of its life. The US health care system has no mechanism to link demand, supply, and price.

The HMOs (Health Maintenance Organisations) that administer the private health care system have very little incentive to reduce costs as the bigger the health care spend, the bigger the profits. The end user of the “insurance” doesn’t really feel the cost of the “insurance” as it is paid by their employer, so they are effectively cost indifferent. Finally, there is no incentive for the suppliers of health care to reduce costs as the HMOs are more than happy to fund more expensive procedures in-line with their incentive structure.

Importantly, HMOs don’t work as “insurance” in the same way as the rest of the world generally defines it, in which there is an insurance policy that covers you only for those times of misfortune, either an accident or some other sort of catastrophe that someone wouldn’t reasonably have the savings to get through. The HMOs cater for everything, as do the US public systems of Medicare and Medicaid. The HMOs are meant to be the gatekeepers of the system, ensuring supply and demand is met while keeping prices in check, but they have no incentive to.

Despite continual efforts by US Congress to keep a lid on costs by installing new rules and regulations on how the system runs, these are always gamed. Ultimately the key factor that keeps the system in its stasis is that nobody in the chain – HMOs, doctors, patients – really care about the price their services are delivered at.

If nobody cares about price, you’ll have a system that costs 2.5 times your nearest comparisons per patient. The costs have real effects as well. The deficit for Medicare and Medicaid are unsustainable and are currently raising the Federal debt burden, and rising health insurance premiums eats into disposable income for employees as premiums are part of total compensation. Goldhill estimates that the average person will put $1.2 million into the US health care system over their lifetime.

The US health care system is a fascinating example of a failing "combination” economic system. Here we have a system that is simultaneously administered by public and private institutions, both achieving equally poor outcomes. If the US couldn’t easily raise external debt to pay for these inefficient services, an avenue not available to the USSR or Venezuela, the health care system would’ve collapsed a long time ago. They deliver the outcomes that you could imagine a Soviet style system would.

This is not to say that the HMOs, pharma companies and health care providers aren’t acting in a capitalist manner. They definitely are. My favourite anecdote in Goldhill’s book was one in which a drug company, concerned with slow sales against a competitor, raised prices to be more competitive and lift volumes. They are merely maximising profit within a framework that is dictated to them by the government. This mix, however, causes an outcome that is horribly inefficient and wastes capital and resources.

A system where such bad outcomes and inefficiency seems to go against the benefits of capitalism that introduced earlier. In fact, it seems to have the disadvantages of both system. The irony is that the US health care system is present in capitalist America, the same capitalist America that is meant to be far more capitalist than the rest of the developed world. This is not to say that a Medicare-for-all scheme would achieve any better outcome, because the core of the system doesn’t allow Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ of the market to guide pricing to the equilibrium.

Free markets and price discovery

Just because the US health care system is privately run, it doesn’t mean that it represents capitalist ideals, and therefore outcomes. It could, in theory, be considered ‘fairer’ as all medical costs are shared, but many would dispute this point as well, given that if you aren’t employed (and therefore have medical insurance) or within the groups that allow you Medicare or Medicaid cover, you must get your health care by waiting in the emergency room of your nearest hospital.

The US health care system is run ‘privately’ yet doesn’t look like it is really ‘capitalist’. The reason why people conflate the two is that ‘private’ is usually considered to be ‘free market’. The difficulty in identifying whether something is capitalist or not is in determining what is operating as a ‘free market’ system and what isn’t, without necessarily relying on the relevant organ of power being clearly identified as a private corporation or public bureaucracy.

Allowing price discovery in as much of your economy as possible is the key to deriving as much as possible from the benefits of capitalism. Allowing price discovery enables each person with a dollar to spend to “vote” on what goods and services should be available, and at what price. This idea is closer to the pure democracy, in which each person has a vote on what direction society should go in. Both democracy and capitalism rely on distributed decision making whenever possible.

Measuring price discovery in developed economies

Let’s accept that a system that embodies the values of ‘capitalism’ as using the free market for price discovery wherever possible and limiting decision making by diktat to only parts of society where the free market doesn’t work. From this point on, we will describe the optimal mix of capitalism and socialism as the free market. Anything else is considered less free, and as a result, more inefficient.

The question is how do we measure how much price discovery is occurring? This is easier said than done.

Think about the issue of corporate regulation. Regulation is something most would agree is a necessary function of government. Nobody wants to be in a society where a company can pollute the local river in the name of profit or collude with a competitor in the interest of raising prices.

What about regulation in which certain types of businesses or products are preferred over others? Or regulation which preferences a certain technology over another, giving the chosen technology an artificial advantage? There are scores of examples of these types of regulation which have ended up delivering a worse outcome that only becomes clear with the benefit of hindsight. If you are wondering why the SUV is the most popular type of new vehicle and why small vehicles are disappearing from the market, it is because CO2 limits for larger cars are more lax, incentivising manufacturers to abandon small cars in preference for larger, heavier cars. Nobody in their right mind would suggest this is beneficial for anyone, or the environment.

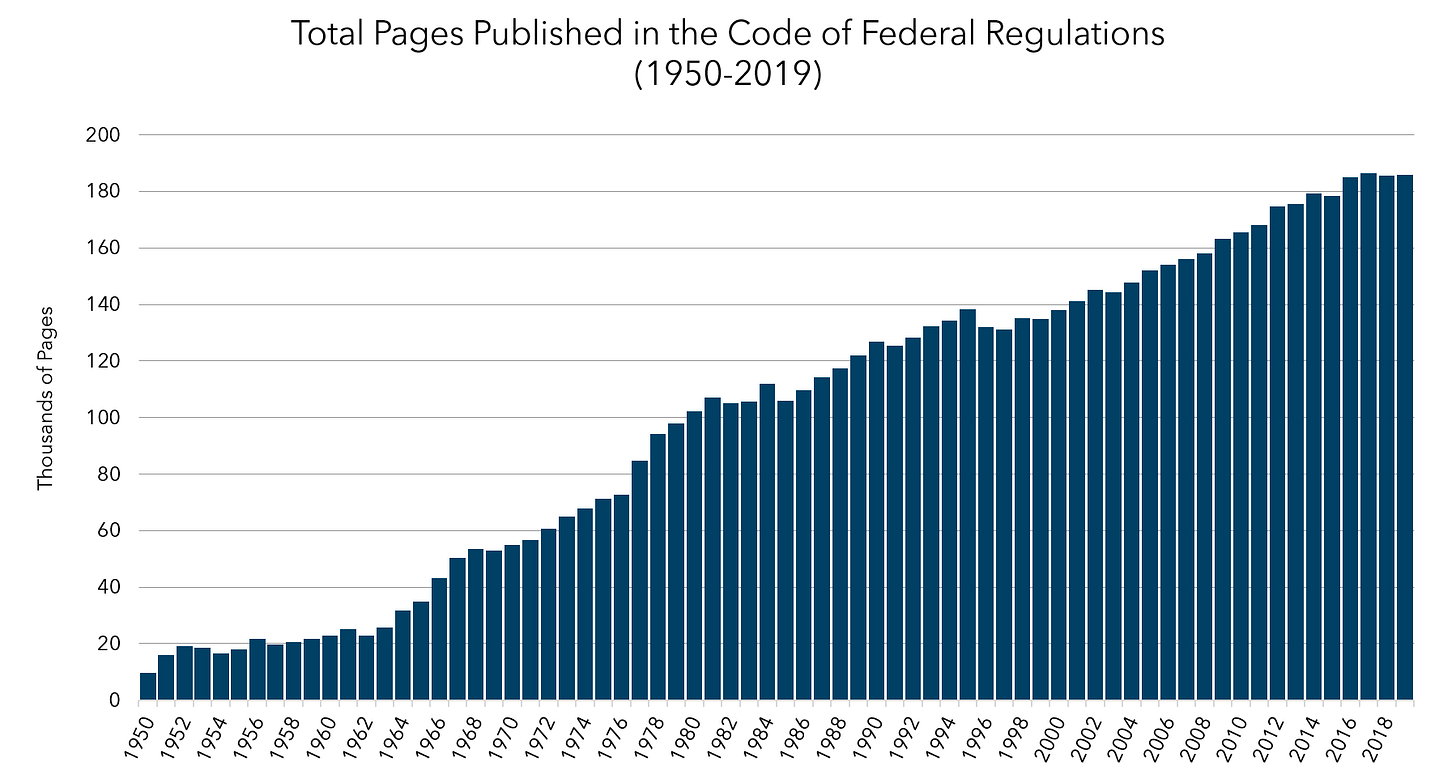

The more rules and regulations there are, the more chance they are of the kind that limits price discovery in the economy. Therefore, as rules and regulations have built up over time, as in the chart below, the trend is towards less price discovery, sliding towards the left of our communism-capitalism continuum.

Revisiting the health care system, climbing spending could indicate greater coverage or a “sicker” populace. These two things are counterintuitive, however, as higher spending should be producing a healthier society, not the other way around. If prices are spiralling out of control, then the system isn’t working properly. This could be because of the skewed incentives from a system that does not allow price discovery, therefore the larger it gets the less capitalist the US economy can be declared to be.

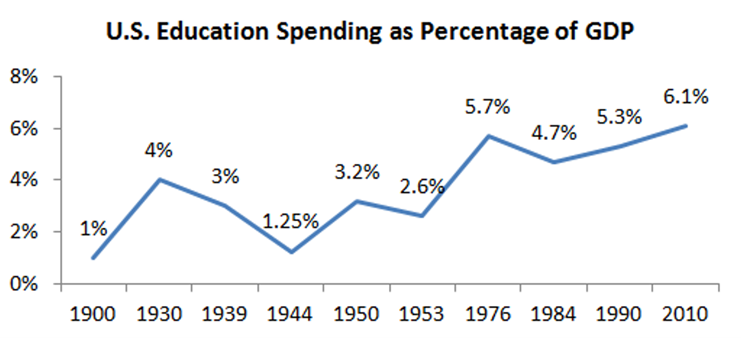

Contrast this with long-term education spending in the following chart. While there has been a slight increase in spending as a proportion of GDP over time, it is not meaningful in comparison with what has happened to health spending. This may be an indication that the system allows correct price discovery.

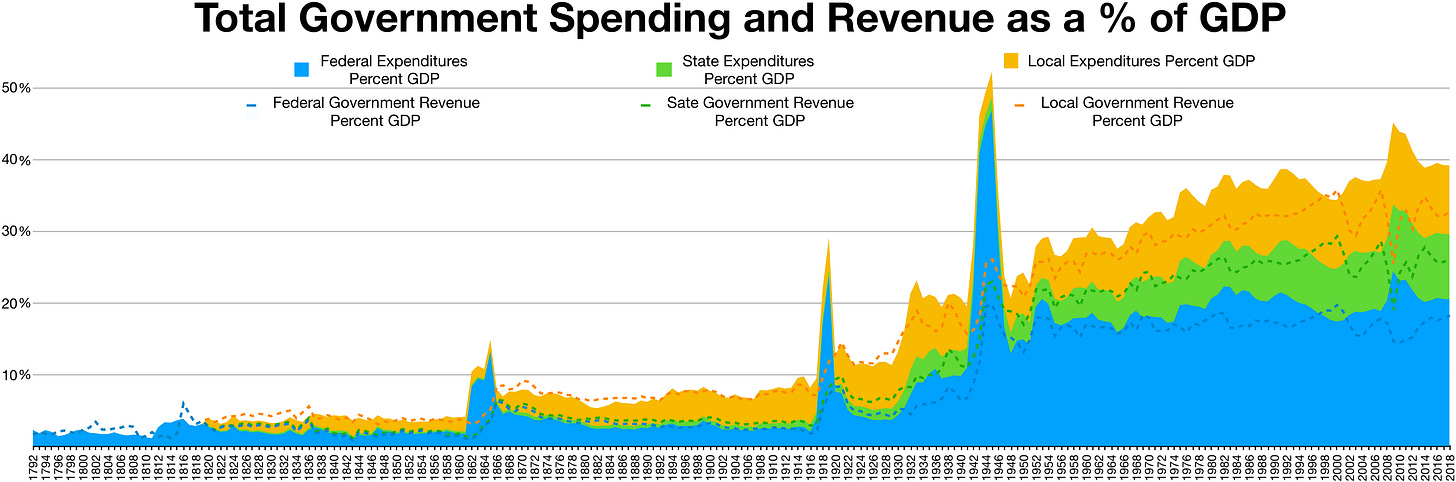

Finally, taking a snapshot of total government spending might be a way to see how big government decisions and government allocation of capital is reducing price discovery in the economy.

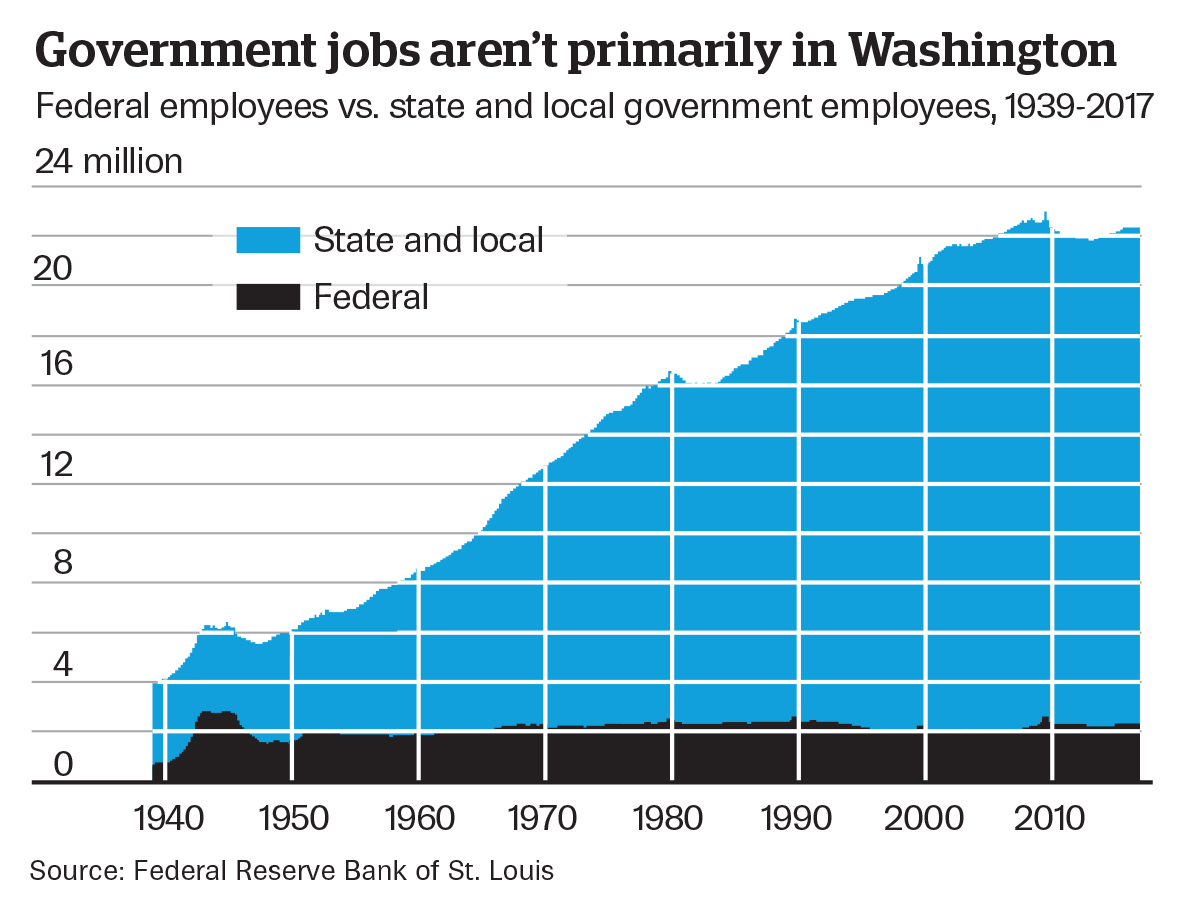

Of course, the increase in government spending could be because of the private sector failing, and the ‘free market’ not delivering as efficient an outcome as what the public sector can. Tending against this argument, however, is the fact that the public sector has seen employee expansion well beyond population growth, a rate far faster than would be explained purely by the country becoming bigger. Government is bigger relative to the population that it governs.

The Index of Economic Freedom

The charts included above illustrate how certain trends in government size can be an indication of a shrinking free market. It is not a complete answer, obviously, as other factors could also explain this shrinking.

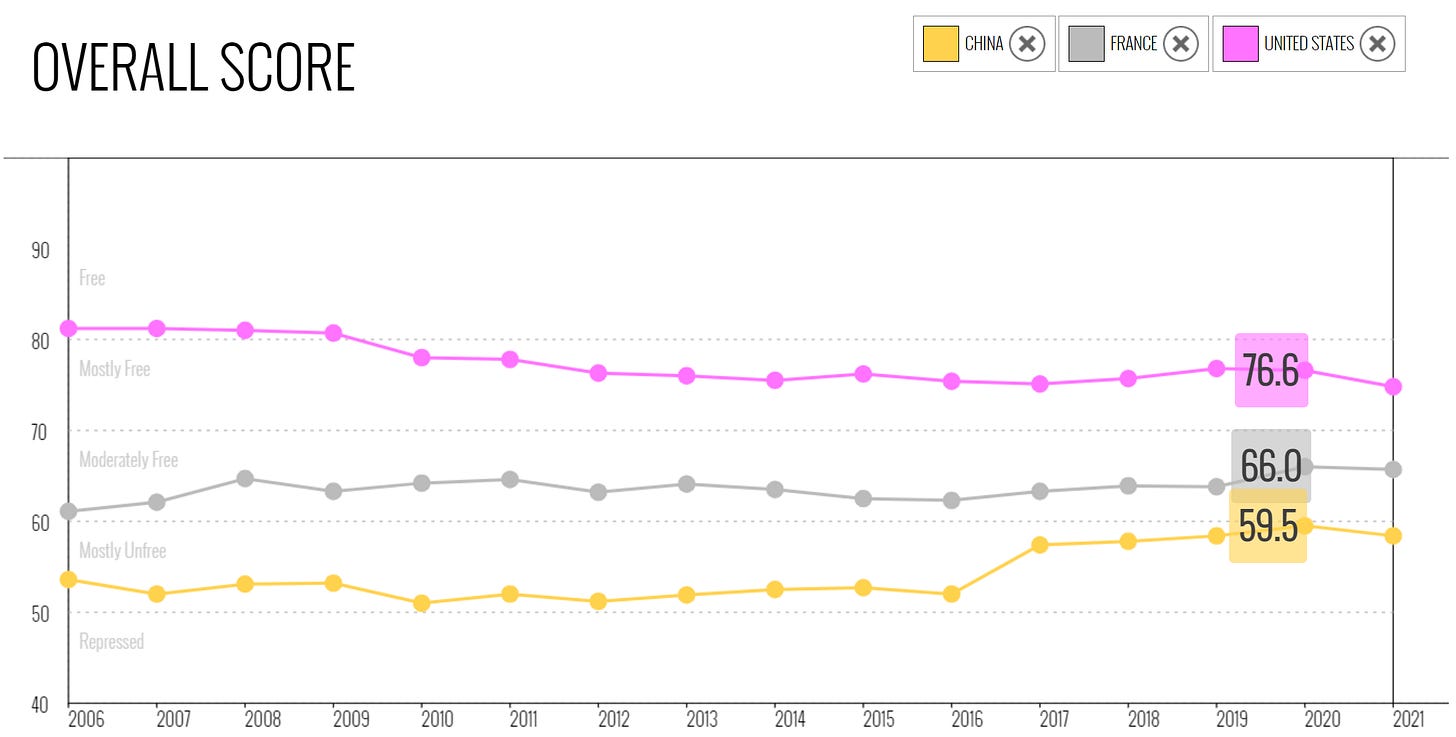

The Heritage Foundation Index of Economic Freedom takes into account more factors than just the size of government, even though this is an important input.

The Foundation explains on its website:

We measure economic freedom based on 12 quantitative and qualitative factors, grouped into four broad categories, or pillars, of economic freedom:

1. Rule of Law (property rights, government integrity, judicial effectiveness)

2. Government Size (government spending, tax burden, fiscal health)

3. Regulatory Efficiency (business freedom, labour freedom, monetary freedom)

4. Open Markets (trade freedom, investment freedom, financial freedom)

Considering all these factors, the US ranks at 20th in the world for economic freedom, not exactly the shining beacon of capitalism that we might expect.

The more concerning issue is that only 3 of the 12 indicators point to more economic freedom since the GFC. This is against a trend of rising freedom for most other large nations, China included. This would suggest the US is becoming less capitalist.

Monopolistic capitalism is not what people want

On these measures, the governing environment seems to be trending away from encouraging a free and open economy to one that is more centrally controlled. On the other end of the spectrum, there are many examples of markets that are taking on the negative attributes of extreme capitalism that I spoke about before, in which monopolistic tendencies are reducing efficiency, customer satisfaction and encouraging capital hoarding. Monopoly like positions are built in particular industries and competition within those industries is impossible. These are sectors that should attract government regulation, but aren’t.

The technology sector is displaying the attributes of a non-competitive, monopoly dominated system. The proliferation of the internet was meant to usher in the era of ‘friction-free capitalism’, according to Bill Gates. He wrote that “the information highway will extend the electronic marketplace and make it the ultimate go-between, the universal middleman.”. What has ended up happening is that a handful of ‘platforms’ have emerged that capture nearly all of the revenue and are difficult to compete against.

Apple’s iOS and app store dominate mobile and app delivery. Google’s YouTube and Netflix dominate video content delivery. Facebook’s multitude of platforms dominate social and chat. Amazon’s storefront and provision of warehouse and delivery services for third-party sellers dominates retail.

It therefore shouldn’t be a surprise that these monopolistic platforms are the biggest companies in the world today, with concentration heavily focussed on those that have been able to capture monopoly rents.

Government has been reluctant to regulate the technology sector in the US, so it has enjoyed unfettered growth. This could be due to the global dominance the US tech sector has, with the US government taking care not to kill the ‘golden goose’. It could also be due to effective lobbying from the tech sector.

The lack of regulation of tech companies has allowed concentration of activity in just a few companies, which in turn has limited the possibility of competition from new market entrants. Nobody would care how Facebook chose to censor anything on its platform if there were 10 other choices; similarly mobile app prices would go down if an iOS user had 5 different app stores to choose from. This concentration has a real effect on free market efficiency.

In areas where capitalism is unbridled, we have seen the monopolistic type becoming more dominant which is moving the US further away from the preferred ideal, while government decision making is heading in the opposite direction. The favouritism that government is practicing between industries that it sees and ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ is causing real damage.

Hidden financial repression

While the Index of Economic Freedom attempts to measure a whole host of factors quantitatively to evaluate how free each market is, it does not measure developments in open capital markets. Monetary and investment freedoms are measures of individual freedom in a free market society, rather than the measure at the macro level of market freedom.

For the savers in a population, low rates are seen as repressive as it affects their ability to earn from the capital they have previously accumulated in their lives. This affects those that are in retirement and approaching retirement.

The flipside of this effect, and the ultimate reason why low rates have been implemented, is that it helps those that don’t have savings by reducing the cost of borrowing. People who don’t have savings generally have a larger propensity to spend each incremental dollar, providing more of a boost to the economy. This could be considered socialist policy as it is intended to redistribute wealth to the poorer members of society, with the hope of achieving a better outcome for all.

The failure of this policy is that it ignores the effect that low rates has on lifting asset prices. Low interest rates make funding cheaper for those willing to leverage into stock, housing, or even speculative investments. It also allows those that are targeted by low interest rate policy to take on more debt for an asset with the same amount of utility, favouring those who had the savings needed for a deposit for a house, for example. It may end up not helping those the policy is intended to help.

This is the basis for the “FU” trade described in another Macro Is Dead newsletter (read “Crypto & moonshots: the FU trade”). The people that are facing higher asset prices for key needs such as housing are acutely aware of how low interest rates and other extraordinary policy is affecting asset prices. They leverage this into more accessible assets as covered in that newsletter, accepting that fighting the tide is worthless and you may as well take a “shot at the moon” with highly speculative assets.

The interference of central banks in driving prices of all assets due to policy that is tailored towards reducing volatility and market disruption is by far the most significant socialist policy. It trumps any discussion on health care, or financial regulation, or government spending. Settings the price of capital (otherwise known as the interest rate), forces the economy along a path of decision making that affects everything. It makes some industries viable and others not. It makes some assets affordable and others out of the reach of everyone but the wealthiest members of society. It can save some people from losing money when they should, at the cost of making life more difficult for those who haven’t gathered many assets.

If central banks make bad decisions on the level of short term interest rates, the free market is only an illusion. This is a key theme for the newsletter in general, and it will be explored more in the future.

We are drifting away from a previously successful system, and everyone is becoming more angry

Government interference and regulations are becoming a bigger part of how economies function in democratic states. This reduces the size of the free market and the price discovery necessary to ensure prosperity. Larger government should be making society fairer – yet more people are angry that society is unfair. Those on the right are unhappy government is getting bigger, and those on the left think that government isn’t big enough. Both side of politics are confronting the same issue – that it is getting harder to achieve the same quality of life that previous generations did.

The trends in economic fairness are occurring because of the macro level effect of central bank policy. I don’t point the finger at any individual central bank, as the trends have been global. All central banks are at fault for their insistence on doubling down on low interest rate policy over and over again.

If you lean more towards socialism or communism, you may reject the claim that free markets achieve a better outcome for everyone. You probably see the role of the US Federal Reserve as still too ‘free’, even though the key decision, being the level of overnight interest rates, is determined by a group of academics.

I suggest it is instructive to look at the effect that having rates set by a group of learned people has had on fairness. It has made things less fair, and this observation should help governments to understand that having free prices is more beneficial to society overall.

Just as the smartest person in the history in the world couldn’t possibly determine how many “remote control poos” should be manufactured to satisfy demand, a group of the smartest people in the history of the world are still human, and they are unable to correctly determine the effect of low interest rates on an infinitely complex economy. This decision has far more implications for everyone than any other economic decision.